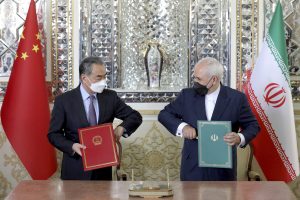

On March 26, Iran and China signed an agreement expressing a desire to increase cooperation and trade relations over the next 25 years. This Strategic Cooperation Agreement, as it is officially known, has been hailed as a massive overhaul of Sino-Iranian relations that will see China invest anywhere from $400 to $600 billion in Iran, with some estimates running as high as $800 billion.

Proponents of the deal hail the onset of mutually beneficial relations between two influential Asian countries with a shared desire to reduce and resist U.S. influence in the region. China is seen as a vital lifeline for a country weakened by sanctions and diplomatic isolation. After eight years of courting the West with nothing to show for it, many Iranians across the political spectrum are hungry for a new way forward. China represents a change of course – whether as a new potential partner or a “China Card” for leverage in Iran-U.S. negotiations.

Opponents paint a much bleaker picture. Some analysts have expressed concerns that the deal threatens U.S. goals in the Middle East, or the fundamental stability of the region itself. Others have gone further and explicitly called China and Iran “the new Axis of Evil.” On social media, Iranians have decried rumors that the deal will lead to nuclear waste dumped in the desert and islands in the Gulf sold to China. The agreement has been called a “New Treaty of Turkmanchay,” referring to the 19th century treaty that saw Qajar Iran cede territory to the Russian Empire. Others claim that Iran will be flooded with Chinese workers and crime-ridden Chinatowns.

Between the clashing narratives of the agreement “selling Iran to China” and “America defeated,” what is the truth of the matter?

The text of the agreement has not yet emerged, and likely will not be published, so all analysis must be tempered with caution. However, a draft of the agreement leaked last summer, and it is unlikely the text substantially changed in the intervening six months. Furthermore, multiple outlets report that their sources have said there is little changed from the leaked agreement. What can be said about the deal based on this leaked draft?

No Specific Commitments, No $400 Billion Investment

First off, nowhere in the text of this or any other official document or pronouncement is any numerical figure mentioned. There are also no provisions whatsoever for the sale of islands, military bases, occupation, or anything that would sustain the other alarmist claims. This has been thoroughly debunked by multiple scholars, and a quick glance at the text will confirm their claims. While the draft itself appears to be genuine, the claims of $400 billion of Chinese investment and massive military concessions can be traced to a poorly sourced Petroleum Economy article from 2019, which has since been taken offline.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian said the day after that the China-Iran Strategic Comprehensive Agreement “neither includes any quantitative, specific contracts and goals nor targets any third party, and will provide a general framework for China-Iran cooperation going forward.”

The same day, Reza Zabib, head of East Asia at Iran Foreign Ministry, called the agreement a “non-binding document.” In response to why the text has not been published, he claimed that “there is a legal requirement to publish agreements; however, the publication of non-binding documents is not common.”

Both sides have now admitted that the plan contains no “quantitative, specific contracts” and is a “non-binding document.” In my view, this confirms what was signed was little changed from the leaked agreement last summer. The agreement can best be described as an aspirational document. It is a signal that Iran may grow closer to China, but not a guarantee. It provides no methods for enforcement, measurable goals, or specific programs. It calls for vague “cooperation” through “enhancement of contacts” in several areas. China also pledged to increase investment in Iran tenfold in 2016, with little progress to show for it five years later. In fact, Chinese investment has decreased substantially since then.

It is notable that both pledges came in the wake of a new U.S. president with a new foreign policy. This does not mean that China-Iran ties are driven by U.S. policy, but the tendency to trumpet them, and exaggerate them, is partly driven by the desire to project strength internationally.

A Mutually Beneficial Agreement? Economic, Political, and Trade Ties

Whether the agreement would be “mutually beneficial” depends on what perspective one takes. For the Iranian state, it provides several benefits: a stable partnership with China means a stable market for oil at a time when U.S. sanctions have seriously hurt its revenues. It also projects an image of strength and represents an attempt to break out of the diplomatic isolation imposed by the United States. For China, it provides similar benefits – a stake in a major source of oil (although Iran provides a tiny fraction of China’s overall oil imports), a large foreign market for Chinese goods (although one that requires a lot of investment), and both real and symbolic progress toward the realization of the Belt and Road Initiative and the expansion of China’s global reach.

From the perspective of the Iranian people, things look very different. Questions of “selling Iran” aside, closer relations with China remain unpopular with many segments of the Iranian population, who often object to the flood of cheap, low-quality Chinese goods, which wreak havoc on the local economy and cause a “race to the bottom.” Some do not consider China a stable partner, pointing to the fact that it has pulled out of many deals with Iran in the past. Rather than asking if the agreement is mutually beneficial to China and Iran, it would be better to consider a different version of that question: “Who in Iran and China does it benefit?”

Reports in the Iranian media have reflected this hesitation. The official Fars News agency described the agreement as “somewhat ambiguous, and on the other hand, in some cases, Iran has had bitter experiences in dealing with other countries. It has pros and cons.” The report discusses general plans for cooperation between banks and infrastructure projects related to the “New Silk Road” and the Belt and Road Initiative, but acknowledges the agreement is a “roadmap.” Discussing technology transfer, it urges that “if Iran wants to make progress… it should not wait for the other side” and needs to develop “a long-term plan” before entering into specific agreements. Chinese investors are “encouraged” to invest in Iran’s various free economic zones, such as Maku along the Turkish border, Qeshm island in the Strait of Hormuz, and the strategic Arvand Free Zone near that Shatt al-Arab. However, the paper admits that while these areas were created to attract foreign investors, “the infrastructure that exists in our free zones, unfortunately, has not been able to actively attract even domestic investment.” In other words, the Chinese side has yet to commit to specifics and historically has been reluctant to do so.

While the deal has a significant amount of support among Iran’s business community and at multiple levels of government, other factors complicate further investment. Chinese companies are not likely to openly invest huge amounts while vulnerable to sanctions. But there are other barriers as well: Due to the bad reputation of Chinese goods, many Iranians are reluctant to buy them, and both sides grumble about the difficulty of dealing with the bureaucracy of the other. Although often directed to focus on specific areas or countries in line with diplomatic initiatives, a business must remain profitable, and both sides must be willing to do business on the micro level as well as the macro level.

Defense and Strategic Concerns

In terms of defense, the items mentioned in the draft agreement – joint military exercises, sharing of intelligence related to terrorism, cooperation on international crimes – are all things that already exist, and so represent no great shift in policy even if they become more formalized. They are also already in place with most neighboring Gulf states. In fact, China has similar Strategic Cooperative Agreements with five other countries in the Middle East, including Saudi Arabia and the UAE, Iran’s regional rivals. It also has such agreements with Russia, India, Egypt, Pakistan, Ireland, Qatar, and others. In short, this agreement represents an attempt to bring China-Iran relations back in line with the rest of the Middle East and its international outreach efforts, rather than expansion of beyond the norm for China’s engagement with the region and the world. Any increase in relations going forward is likely to be in line with and balanced against relations with other Gulf states.

That said, the deal does offer some strategic advantages to Iran. While China has no real capacity to oppose the sanctions or even things like the U.S assassination of Qassem Soleimani, the prospect of increased Sino-Iranian relations does provide the Iranian state with some breathing room and room to posture. It may even positively impact the prospects of resuming the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), as the Iran nuclear deal with the U.S. is known. During a Q&A session on the social media app Clubhouse, Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif said, “We were able to jump start the China strategic deal thanks to the signing of JCPOA. Before that the Chinese were not replying to our overtures.” This is consistent with statements from Beijing at the time of the signing of the JCPOA, the 2016 commitment, and today. Improved Iran-U.S. relations are a precondition to increased Sino-Iranian economic involvement. The Biden administration has expressed “concern” over the partnership, but it has also agreed to attend a summit this week in Vienna involving China, Iran, Russia, and the EU. The outcome, however, is far from certain.

Conclusion

Since the agreement was officially signed, a chorus of experts on China-Iran relations have weighed in on the significance of this agreement. Jonathan Fulton, a senior fellow at Atlantic Council and assistant professor of political science at Zayed University in Abu Dhabi, called it “a list of things [Iran and China] hope to do, under perfect conditions.” Jacopo Scita, a doctoral fellow at Durham University, called the agreement a “mirage” and a “details-shy plan” that should not cause the “panic” it has in Western commentary. Lucille Greer and Esfandyar Batmanghelidj, two researchers who have analyzed the leaked draft extensively, have argued in the Washington Post that the agreement is “not as alarming as it sounds.” Fan Hongda, a Chinese academic at the Middle East Studies Institute at Shanghai International University, called the agreement “just a roadmap” that depends on “the strength and depth” of future Sino-Iranian cooperation.

Caution must be taken not to minimize the deal entirely. It is not “fake news” that China-Iran relations are likely to improve. It carries great symbolic significance and allows the Iranian state some room to posture and negotiate. However, alarmists who push for a more aggressive stance toward both China and Iran based on this deal are massively exaggerating its terms.

Is there an expansion of Sino-Iranian relations in the works? Yes, and it is significant. It will see increased investment and linkages between the countries. But there are no specifics, no indication of $400 billion worth of investment forthcoming, and no indication of unprecedented military cooperation or Chinese troops being stationed in Iran. The fact is, we have no reason to believe that the deal is a massive shift in China’s international policy, and every reason to believe it will be balanced against China’s relations with the U.S. and other states in the region, including Iranian rival Saudi Arabia.

While China remains Iran’s top oil importer, Chinese firms have not increased investment, imports, or exports at the exponential levels pledged in 2016, and are not likely to do so in 2021 either. The deal is unlikely to fundamentally threaten the balance of power in the Middle East. China tends to choose stable relations with geostrategic advantages over volatile ones likely to spark conflict. For all its propaganda, China, like Iran, is more interested in its immediate geopolitical goals than a revolution.