As Zubi (name changed by request) walked over to the entrance of a vaccination center at Karachi’s biggest government-run hospital, JPMC, she was greeted by a long queue forming on the road outside. She glanced at her phone to check the time: it was 7:45 a.m. The brochure said vaccinations would begin at 8:00 a.m. In typical Pakistani fashion, the staff arrived at 9:00 a.m.

The mid-March morning was already hinting at a gruesome summer ahead, discouraging people to stand in a line of over a hundred people. Many gave up and left. Those who tried to cut the line were escorted to the very end by two spirited men in their 60s, vowing to ensure discipline.

***

Pakistan surprised everyone, even itself when it managed to limit the spread of COVID-19 in the first and second waves. The current third wave, however, is a different story. With over 2,650 dying of coronavirus by April 25, 2021, the monthly death toll is close to breaking the previous record of most deaths, when the virus claimed over 2,800 lives in June 2020.

At 10.62 percent, the positivity rate of this month is mirroring last April’s (10.15 percent). A report by the country’s Planning Commission showed the R-number for Pakistan “ranged between 0.74 to 1.66 since the beginning of the pandemic.” This year, it has gone from 0.94 in January to 1.40 in April.

With 1,213 deaths and 34,937 cases, the highest fatality ratio was witnessed in February 2021 at 3.47 percent.

A recent study conducted in Karachi revealed that the rise in infections and deaths during the third wave is most likely due to the spread of the U.K., South African, and Brazilian variants of COVID-19. The analysis found the original virus in 1,653 samples, the U.K. variant in 944 samples, and the Brazil and South Africa strain in 934 samples.

Additionally, experts at the National Institute of Virology at the University of Karachi found that around 50 percent of the positive cases tested at the facility involved the U.K. strain while 25 percent were the South African variant.

Studies have shown these variants may be more contagious and dodge immunity to some extent.

“The more the virus has the opportunity to transmit between individuals, the more chances it has to develop new mutations,” said Amesh A. Adalja, a senior scholar at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. He explained that community spread would continue until a significant proportion of the population, including those at high risk of spreading the virus, is fully vaccinated.

Outside a COVID-19 vaccination center at the Jinnah Post-Medical Center (JPMC), Karachi’s biggest government run hospital, on a mid-March morning. Photo by Niha Dagia.

Vaccines and Hesitancy in Pakistan

At about 9:45 a.m., it was finally time to go inside the vaccination center. After filling out a medical form and getting a digital verification, Zubi was handed a vaccination card and directed toward a vaccination booth to get the shot.

Zubi was given the Sinopharm vaccine – a gift from China.

***

Late to the party, the Pakistani government was saved by China and Russia’s “vaccine diplomacy” as the COVAX Facility continues to face delays. Since late February, a million doses of Sinopharm, half gifted by China and half bought by the government, have arrived in the country along with 600,000 doses of single-shot CanSino vaccines.

Another 2 million doses of Sinopharm and CoronaVac are expected to arrive on May 1, half a million of which are a gift from China. Pakistan will also receive 10-15 million doses of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine by July, while provincial governments in Punjab and Sindh have also placed orders for Chinese vaccines.

Currently, government rollout is limited to those aged 50 and above. Younger Pakistanis are being catered to by the private sector, which procured 50,000 doses of Sputnik V and is awaiting another 150,000.

According to the National Command Operation Center (NCOC), over 1.8 million Pakistanis have been vaccinated at government facilities while over 18,000 received shots at private hospitals – in total, less than 1 percent of the country’s population. Considering the rollout began on March 9, Pakistan has vaccinated about 40,000 people a day. At this pace, it would take more than two years to cover 10 percent of the country’s population.

“At this time, we are focused on self-registered citizens in various age brackets,” Federal Health Minister Dr. Faisal Sultan told The Diplomat.

For a country with a 59 percent literacy rate, registration through SMS and a website creates an apartheid situation.

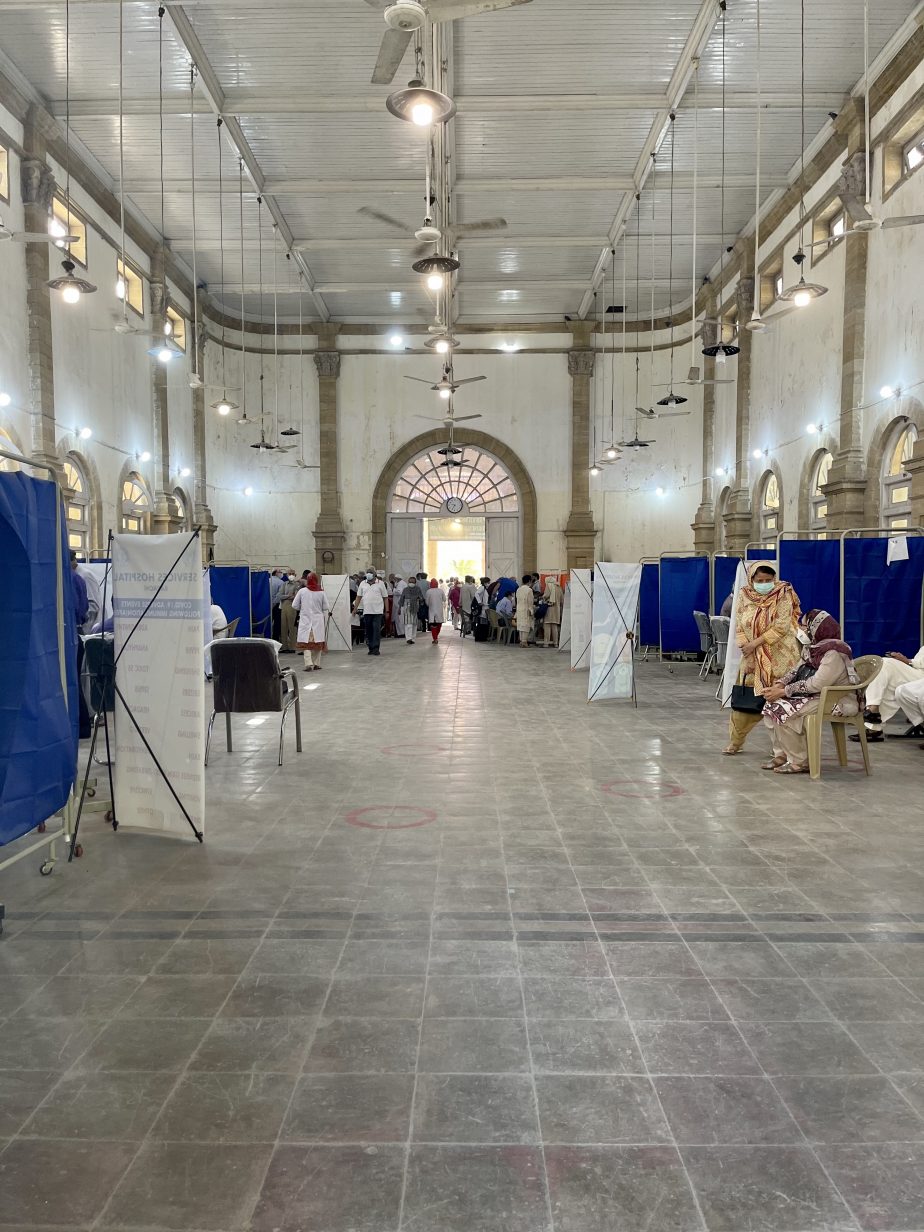

Inside the COVID-19 vaccination center at Khaliqdina Library Hall in Karachi on a mid-March morning. Photo by Niha Dagia.

“We have integrated Rural Support Program that has over 1,500 representatives across 169 districts who communicate NCOC’s messages in regional languages through local networks such as announcements in residential blocks and mosques,” stressed an NCOC source. “Since over 83 percent of Pakistan’s population uses mobile phones, we broadcasted more than 3,000 million PSAs via ringtones.”

Dr. Seemi Jamali, executive director at JPMC, said the center has vaccinated over 30,000 people, the majority of whom are from the affluent sections of society. “The reluctance is due to myths such as [the] vaccine causing infertility or changing genetic codes as well as people believing COVID-19 to be a conspiracy,” she said.

The fact that Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan and President Dr. Arif Alvi both tested positive for COVID-19 after receiving vaccinations added fuel to the fire, giving anti-vaxxers grounds to describe the vaccine as useless.

On the other hand, epidemiologist Dr. Rana Asghar thinks Pakistan’s vaccine rollout may hit a snag when Oxford-AstraZeneca doses arrive in millions amid confusion regarding the potential side effect of blood clots. “The government may be unable to utilize the vaccines as people may be apprehensive of the side-effects,” he said. “This may strain our supply line.”

Reluctance isn’t the only hurdle here. Millions of Pakistan’s lower middle-class, including migrants and immigrants and residents of far-flung rural areas, lack proper identity documents, making it difficult for them to register for the vaccine.

Storage and Distribution

At the vaccination booth, Zubi watched as the medical staff took out a vaccine vial from a disposable cooler packed with ice and filled the syringe. Once the vaccine was administered, she was asked to stay put for 10-15 minutes in the waiting lounge to monitor any reaction to the vaccine.

At 10:50 a.m., Zubi headed home.

***

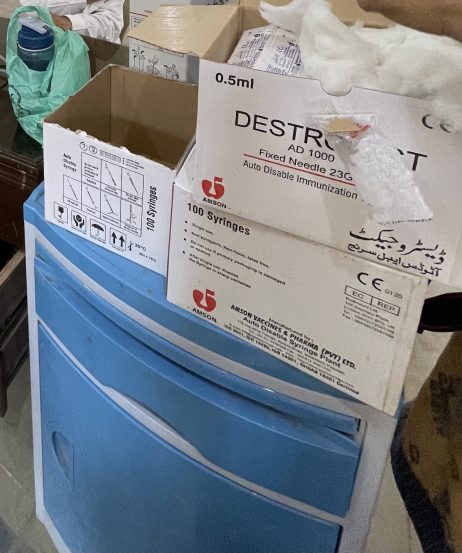

“The vials are stored in the refrigerators when they arrive at the vaccination center,” medical staff at Khalidqina told The Diplomat. “Once the rollout begins, we put them in disposable coolers and bring them to the booths. The ice packs are changed every few hours.”

While the JPMC has an existing cold chain management facility, as it is responsible for the storage of all of the province’s vaccines, such as those guarding against polio and measles, other vaccination centers such as Khaliqdina have been provided with cold storage systems by the NCOC.

“We are using the existing cold carriage with the national Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) for coronavirus vaccine rollout,” said Sultan. It ensures the temperature is maintained at required levels, he added. The federal health minister said there were over 1,000 centers across the country.

Jamali said we need more. She suggested mobile units that can travel around, vaccinating people in the densely populated areas in urban centers as well as the scattered homes in rural areas. “A single-dose vaccine would be much better for mobile units to avoid a second trip,” she said.

Under the EPI program, door-to-door vaccine drives such as the anti-polio campaign have proven to be successful. For coronavirus, things aren’t that simple. The size of an average COVID-19 vaccine vial is larger than that of measles or polio shot hence requiring special transport arrangements.

“The government has procured special vehicles with mobile cold storage systems from China,” said the NCOC source.

“At the moment, home vaccine facility is only available for the elderly in urban centers,” said Sultan.

Inside a COVID-19 vaccination center at the Jinnah Post-Medical Center (JPMC) in Karachi on a mid-April afternoon amid Ramadan. Photo by Niha Dagia.

Power Outage

On a mid-April morning, Zubi was back at the JPMC vaccination center to get a second shot of the Sinopharm vaccine. Unlike last time, there was no line. She walked in, filled out the medical form and got it verified digitally, and headed to a vaccination booth. The entire process took less than 20 minutes.

***

“We have been vaccinating between 800 to 1,600 people a day. Some days up to 2,000 people showed up,” said Jamali. But Sindh Health Department spokesperson Atif Vighio said the pace has slowed down since the beginning of Ramadan. “People are reluctant to get vaccinated during fasts.”

“A slow vaccine rollout will do nothing to staunch the spread of the virus in the community,” said Adalja of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. It would also inundate the healthcare system with storage issues with the temperatures rising.

It is only April and the city of Karachi has seen at least one heatwave. Lying in a temperate zone, Pakistan’s climate is generally arid. Summers in the vast plains of the Indus Valley are extremely hot while northern mountain ranges are extremely cold in winters.

As the temperatures rise, the country also faces a power deficit with some cities experiencing load-shedding (power cuts) for as many as 12 hours a day. Many rural centers receive electricity for a few hours every day – whether in summer or winter.

Therefore, Pakistan is looking to procure vaccines that can be refrigerated during the inoculation process, with a storage requirement that isn’t as low as the minus 71 degrees required for Pfizer. Medical staff at the Khaliqdina center told The Diplomat that their backup during power cuts was an uninterruptible power source (UPS) provided by the government. The on-battery run-time of most UPSs is short-lived.

“The practice is to call people to vaccination centers where electricity is available as it is pertinent to keep the vaccine at the required temperature or its efficacy decreases,” said the NCOC source.

That may not be as easy as it sounds. Even in Pakistan’s largest city, Karachi, all major hospitals suffer prolonged load-shedding and daily power failures that compel doctors to postpone surgeries and other routine work.

There is no reason to doubt things will be any different this summer.