Images of Chinese officials shaking hands with African leaders during diplomatic visits have long been prevalent across global media. But diplomatic visits worldwide are always much more than just a photo-op. Just look at the French Africa Summit held last week. The visits serve as a mechanism to identify areas of cooperation and establish new, innovative initiatives to advance the needs and objectives of both countries.

No country has been more active in diplomatic visits to Africa than China. Indeed, from 2009 to 2018, a total of 82 visits by China’s top leaders to 40 African countries have taken place. Part of an annual tradition by China’s foreign ministry since 1991, these visits are a centerpiece in Sino-Africa relations.

Yet, there is an overwhelming focus on Chinese leaders to Africa, reinforcing the concept of China in Africa. This narrative is powerful, and not only shapes how the relationship between the continent and China is perceived, but has important implications for the deployment of agency in Africa’s foreign policymaking.

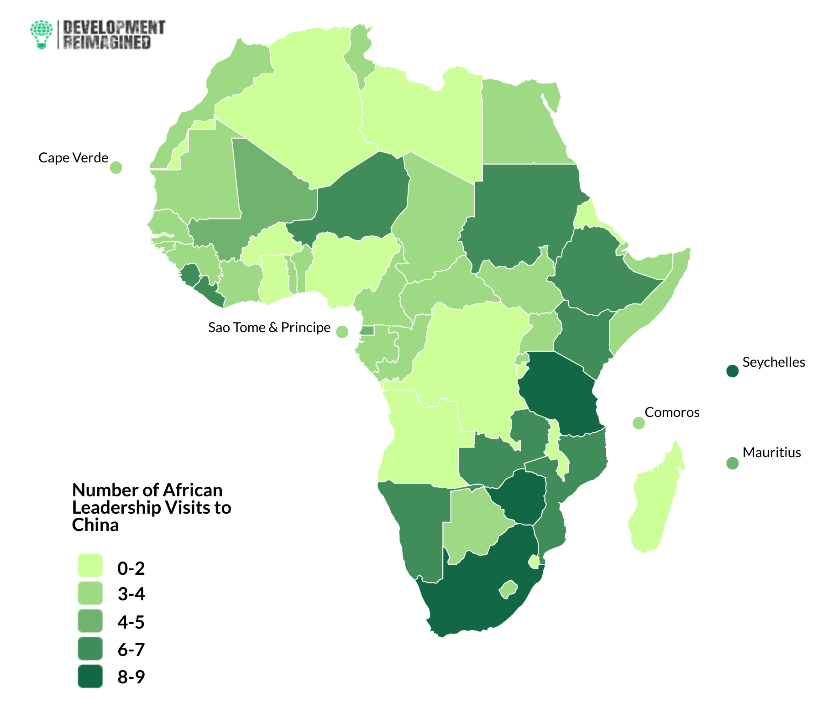

So, what’s the story of African leadership visits to China? Our new analysis at Development Reimagined reveals that from 2009 to 2018, African leaders from 53 countries visited China 222 times. Breaking this down, Tanzania had the most visits to China, with a total of nine trips, followed by South Africa, the Seychelles, and Zimbabwe, with eight visits each.

But visits do not occur on a reciprocal basis. Chinese leaders had not visited 13 African countries during this period – yet 10 of these countries visited China more than three times.

If visits do not occur on a reciprocal basis, what motives African leaders to travel to Beijing?

Many commentators assume visits occur based on China’s economic interests in certain African countries – with pundits often implying an exploitative relationship by pointing to investment in the extractive natural resource sector. Our study reveals a more complex picture, echoing the importance of looking beyond one-dimensional narratives.

Nigeria, for instance, has only received three leadership visits and deployed two to China. This is relatively low considering Nigeria ranked as the top African country in terms of the value of Chinese overseas investment and construction, as well as being the top African trading partner with China. On the other hand, South Africa, which ranks as the third largest destination for Chinese FDI flows and second largest trade partner, received five Chinese leadership visits and deployed eight visits to China.

So what does this all mean? What do visits from African leaders actually achieve – if anything at all? Let’s dig a little deeper.

The first thing to note, while there are some outliers, is that there does appear to be a correlation between African leadership visits and the outcomes on trade, investment, and finance decisions. African agency is clearly in play here, indicative of the phrase “if you don’t ask, you don’t get.”

Take Zambia. Zambia has only received one visit from China but has deployed seven visits. At face value, this may imply that Zambia is less significant in China’s relationship with the continent compared to other countries. Yet, Zambia ranks as the second largest African country for Chinese FDI.

The Seychelles is the most remarkable case. The Seychelles’ leaders visited China eight times over 2009 to 2018, yet they did not host direct Chinese counterparts once over that same period. Importantly, the Seychelles does not rank particularly high in terms of being a destination of Chinese FDI or trade. Why then has the Seychelles sent leaders to China so frequently?

One possibility could be to push the tourism industry – the bedrock of the country’s economy. Indeed, in 2009, the president visited China for a tourism promotion event, and over the following few years, the number of Chinese tourists began to climb. According to the Seychelles National Bureau of Statistics, China ranked as the sixth largest market for the country’s visitors in 2015 and 2016 – accounting for 5 percent of total arrivals each year.

Other studies support our conclusions. Chinese scholars Yan Wenshou and Wang Xiaosong found that, based on African leadership visits to China from 1990 to 2012, there was a correlation between African leaderships visits and increases in Chinese exports in the manufacturing, machinery and transport equipment sector, as well as increases in Chinese aid.

This tells us how the deployment of active African agency can be exhibited strategically to push for what Africa wants and needs from its relationship with China.

African countries do not merely exist in a vacuum in their relationship with China – they have bargaining power and they have agency. And this agency clearly yields results.

So how can more African countries reap benefits during their leadership visits and beyond? The first step is to establish a clear framework for leadership exchanges, to open new space for dialogue and communication.

Too often we hear what African countries don’t want from their relationship with China – bad investments, bad loans, and bad trade, to name a few. But there is an opportunity to articulate what is wanted. As we heard from African ambassadors in China during a retreat our firm hosted for them in 2018, a blueprint is needed – a continent-wide “China Strategy” – to put the relationship with China into context and articulate what goals African countries should be targeting with China. A coordinated strategy is even more relevant in the context of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), now in operation.

A first attempt at a continent-wide blueprint is exactly what we’ve been working on at Development Reimagined. Indeed, despite the more than 200 visits, the fact is that most African nations to date have not coordinated around nor been particularly intentional about how they engage economically with China (nor, for that matter, other development partners), often acting passively as “price takers” when it comes to the nitty gritty issues such as trade and loans in particular. Furthermore, there is little benchmarking against each other or even other regions. Just look at the rest of Asia. Low-income Asian countries have benefitted from the outsourcing of Chinese factories, as well as tourism. Seventy-six percent of the rest of Asia’s exports to China are non-agriculture or mining products, whereas the share for Africa is just 16 percent. Coordinating and benchmarking presents an opportunity to aim higher, and get more out of the China relationship – to ultimately drive poverty reduction and sustainable development.

The fact is, and again despite the visits, China too has suffered from the lack of clear understanding of African needs. Yes, China’s own recent poverty reduction experience helps, as do the visits in both directions, but there are significant negative perceptions of China’s influence in Africa. Having African leaders set and discuss publicly what is needed and achieved with Chinese counterparts, making the case for China’s specific engagement versus other development partners, will no doubt lead to more smart investments to properly optimize cooperation.

There is no doubt that leadership visits matter to African agency. The time has come now, however, for African leaders to make visits that also set out the ambition in their relationships with China that they are trying to achieve. This way the “China-Africa” relationship can perhaps be re-oriented toward an “Africa-China” relationship, driven consistently by what Africa needs and wants from China.