On April 24, Tran Thi Tuyet Dieu became the latest journalist to be jailed for daring to criticize Vietnam’s ruling communist party. Dieu was handed an eight year sentence for criticizing the party and advocating for democracy on social media. According to Reporters without Borders (RSF), Vietnam has one of the world’s most repressive environments for journalists, with only five countries scoring worse in the group’s latest annual report. These are difficult times for Vietnam’s independent journalists, and there is little cause for optimism.

The year 2020 saw a spate of high-profile arrests as six independent journalists were arrested. In October 2020, the authorities arrested human rights and democracy advocate Pham Doan Trang. Trang, who received the RSF Press Freedom Prize for Impact in 2019, was arrested on the day of the 24th annual U.S.-Vietnam Human Rights Dialogue, in a blatant display of the Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP)’s contempt for human rights. She was charged with publishing “propaganda” against the state, a loosely-defined term that is often used to lock-up critics of the regime.

Three months later, in January of this year, three members of the Independent Journalists Association of Vietnam, Pham Chi Dung, Nguyen Tuong Thuy, and Le Huu Minh Tuan, were handed lengthy prison sentences for writing articles which the government deemed beyond the pale. Thuy and Tuan received 11 years each, while Dung was given 15 years. The trio were convicted of spreading “distorted information,” in another example of the authorities using the broad scope of vaguely defined laws to clamp down on dissent.

Arrests of journalists have continued into 2021, with the arrests of Le Trong Hung and Tran Quoc Khanh in March. It is no coincidence that the two critics of the regime were arrested after planning to run as independent candidates in Vietnam’s National Assembly, the legislative body that largely serves to sign off on decisions already made in the Politburo and Central Committee.

The arrests are part of a deteriorating situation for free expression in Vietnam, with social media and online content coming under increasing scrutiny from online censors. In January 2019, the government passed a new cybersecurity law which demanded that technology companies hand over user data and enforce censorship. In April 2020, Facebook agreed to increase censorship of critical content after the government forced the company’s servers offline and restricted traffic to the site. Vietnam may be looking to create its own version of the Great Firewall of China, where content is scrupulously monitored and criticism of the regime is almost impossible. Although Vietnam is not currently powerful enough to do this, the approach it has taken so far suggests that in the long term it may well do so if it can.

Social media in Vietnam is extremely popular, with Facebook boasting around 66 million users, around two-thirds of the total population. Social media can be a forum for political debate, criticism, and the free exchange of political ideas, all concepts which are anathema to the Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP). According to The 88 Project’s annual Human Rights report, 10 online commentators were arrested in 2020. These commentators had no links to civil society groups and were jailed solely for what they posted online.

The crackdown on bloggers and live streamers has also continued into 2021. On April 23, the blogger Le Thi Binh was sentenced to two years in prison for posting and streaming criticism of the VCP on Facebook, and for advocating for multi-party democracy. In December 2020, the former journalist Truong Chau Huu Danh was arrested for campaigning against government corruption, amassing around 168,000 followers on his Facebook page Bao Sach (Clean News), which was shut down after his arrest. On April 20, three more members of the Bao Sach group were also arrested. Both Binh and the members of the Bao Sach group were charged with “abusing democratic freedoms,” another favored tool of the authorities to silence critics.

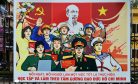

The government would like social media to resemble an echo chamber of official party propaganda. To this end, it has recruited an army of online activists to promote party policy, harass critics, and monitor content for dissent. One favored tactic is to mass report critical content so it is removed by Facebook for breaching community guidelines. In November 2020, Reuters reported that Vietnam had threatened to shut down Facebook, despite the increased level of censorship that Facebook had enforced on the government’s behalf since the agreement in April. The VCP knows that Facebook is unlikely to pull out of such a lucrative market, and is sure to press for even more restrictions in the future.

These are worrying times. As leading journalists are arrested and social media becomes increasingly restricted, it is hard to remain optimistic about the future of independent journalism in Vietnam. Freedom of the press is essential to hold politicians to account, and to represent the interests of ordinary citizens. Activists and journalists have used social media to organize opposition to unpopular laws, campaign against corruption, and protest against environmental destruction. Although taking away this power from its citizens may serve the interests of the VCP, it is ordinary Vietnamese people who will suffer the consequences. The Hardline Nguyen Phu Trong secured a third-term as leader of the VCP at the 13th Party Congress in February of this year, indicating that strict censorship and heavy sentencing is here to stay. That’s bad news for journalists, and bad news for Vietnam.