On June 30, the statement “One quarter of party members are aged below 35” appeared ranked second on Baidu’s purported “hot search terms.” As with much of the country, the search engine’s main page was decked out with a red national flag and “100” in golden letters.

On the centenary of the Chinese Communist Party’s founding, the Party clearly wishes to challenge the perception of an organization dominated by old men, even though the proportion of younger members indicated by that statement doesn’t necessarily prove the point.

The topic of age was clearly front of mind for the producers of the new ensemble movie “1921.” Released on July 1 after a heavy months-long marketing campaign, the film eulogizes various patriots whose ages, as well as names, are displayed onscreen as they are introduced throughout the film.

Ten minutes in, the camera pans across Shanghai’s French Concession to rest on “Mao Zedong, 27” (actor Wang Renjun) stepping off a tram, his eyes sparkling with eagerness to meet other aspiring revolutionaries including “Li Dazhao, 20” and “Li Da, 30.”

Even “Deng Xiaoping, 17” appears: a scene in Paris shows him lathering black ink onto a heavy metal press, as he helps his mentors to print pamphlets decrying the gifting of Qingdao to Japan set out in the Treaty of Versailles. Deng’s thick Sichuanese accent is the target of his Paris comrades’ good-natured amusement.

The feature premiered at the Shanghai International Film Festival on June 20 and was released in China on July 1. It is being distributed internationally, with Chinese consulates and affiliated chambers of commerce supporting other July 1 screenings in cities including Los Angeles and Melbourne.

In pre-sales, the film had grossed 74.64 million yuan (US$11.83 million), according to CGTN.

Produced by China Film Group and directed by Huang Jianxin, “1921” owes its existence to a network of collaboration that has created films promoting China’s “main melody” – the officially approved version of the nation’s history – for over a decade.

The protagonists’ youthfulness and the importance of that for young Chinese pervade the film. Its tagline is “100 years, still youthful.”

“Youth is like the early spring, like the morning sun, like the blossoming of a hundred flowers,” declare the film’s trailers, quoting the article penned by CCP co-founder Chen Duxiu in New Youth, the journal he founded in 1915.

The female stars of “1921” appeared in a promo spot released on International Women’s Day, March 8, 2021, praising early CCP women. (Screenshot via Youku)

Along with the youthfulness of its protagonists, the film emphasizes the role of women.

A glorious entrance is afforded to Wang Huiwu, who strolls into frame down the stairs of a shikuman, the traditional Shanghai dwelling. Her name and age (22) are flashed on the screen, the latter to signal her precocity. She is dressed for her wedding to Li Da, one of the CCP’s founders.

Wang Huiwu started up the earliest women’s publication of the CCP, Women’s Health, and established the Civilian Girls’ School in Shanghai, which was also used as the site of the Second National Congress in 1922.

Equally, the movie extols Yang Kaihui (19), one of the first female members of the CCP and an ally of Mao Zedong in Changsha. She was Mao’s second wife, and their courtship is depicted tenderly in “1921.” Yang’s execution by the Nationalists in 1930 is a scene of climactic pathos and tragedy.

Not every figure receives such tender treatment. Chen Duxiu was a founder of the Communist Party and its first general secretary, but his legacy is complicated. The CCP expelled him and in the 1930s he allied himself with the exiled Leon Trotsky while Mao ascended to the top of the CCP and deepened ties with Stalin’s Moscow.

Chen (40) is depicted in the film as a man with rough edges, unhinged even. He is introduced unflatteringly, confined to his prison cell as fellow CCP co-founder Li Dazhao comes to visit and negotiate with the French Concession authorities for his release, but not before reproaching Chen: “You mustn’t act like a teenager.”

In the late 1920s disputes over cooperation with the Nationalists and the Comintern led to Chen’s exit from the CCP and his becoming a committed Trotskyite before dying in obscurity and poverty in 1942.

In previous historical presentations, Chen was always portrayed as an archvillain, for example in the ubiquitous 1960s opera “The East Is Red” where the narrator proclaimed: “The great revolution failed, thanks to the rightist opportunist policy of Chen Duxiu.” As media studies scholar Chen Xiaomei has documented, Chen has been partially rehabilitated on the PRC stage and screen.

“1921” grudgingly gives Chen credit, though for much of the movie he is referred to as being “away” in Guangzhou, allowing for preferred heroes to upstage him.

No mention is made of Hu Shi, despite the fact that he was one of the most significant contributors to the New Youth journal. Hu became an avowed enemy of the CCP later in the century and a proponent of Western liberalism in Taiwan.

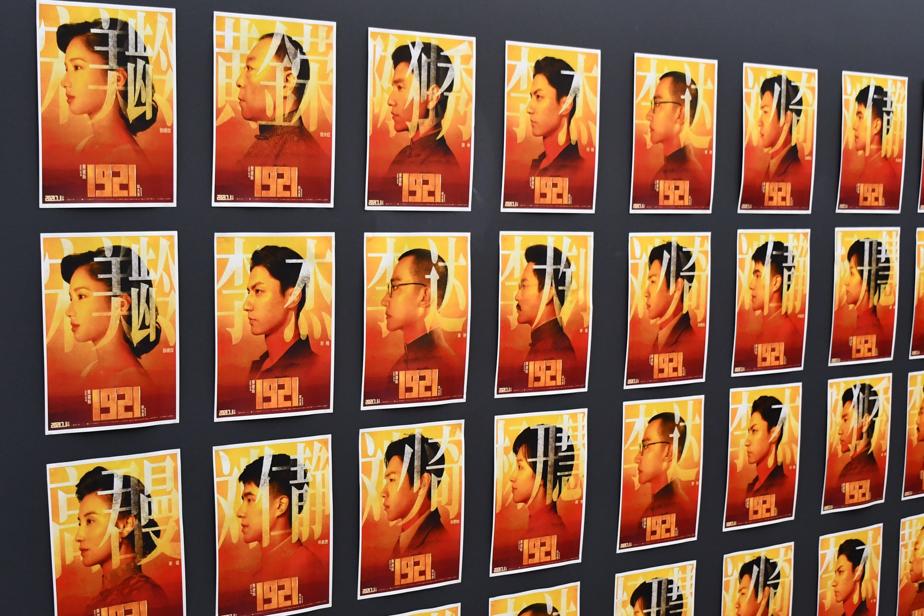

Posters for the stars and characters of 1921 outside the cinema for the Australasian premiere in Melbourne on July 1. Photo by Jesse Turland.

But audiences won’t be going to see “1921” for historical excursus. Naturally, its purpose is not to raise difficult questions, but to inspire audiences, and even thrill them. Li Da and Wang Huiwu combine their revolutionary ardor with a fairy-tale romance. There is a car chase scene with a Russian-appointed Comintern agent in a quaint sedan that performs death-defying mechanical feats to elude his Japanese-appointed would-be assassins.

Rousing speeches abound. “Hope is like a path in the countryside,” proclaims Li Da to his comrades. “Originally, there was no path – but when many people pass one way, a road is made.” He is reading from “that new writer, Lu Xun.”

The fledgling party struggles to organize in the face of gendarmes cracking down on its meetings but finally manages to hold its first congress in the presence of Comintern representative Henk Sneevliet.

When I saw the film at the Australian premiere in Melbourne, it was prefaced by a music video. This featured the cast of the film taking turns singing lines from the pop song “Youth” (“Shaonian”). The story of the PRC’s glorious history is told in a montage throughout the song, featuring AI-enhanced shots of Mao proclaiming the People’s Republic in 1949, spliced with footage of the Chinese space program, the handover of Hong Kong in 1997, and even the border confrontation with India at Doklam last year. The music clip concludes with a kindergarten-aged girl singing the closing lines of the song, paralleling the conclusion of the movie itself, in which kindergarteners gaze in awe at the Shanghai house where the CCP was born 100 years ago.