A fire that broke out in a food processing factory in Narayanganj in Dhaka on July 8 has claimed the lives of at least 52 people with many missing, including 16 children aged between 13 and 16.

The deaths caused an uproar in Bangladesh, with people clamoring for justice and accusing the factory owners, the Sajeeb Group, of negligence.

When news of the fire broke, a defiant Abul Hashem, managing director of Sajeeb Group, told media that he “didn’t start the fire.” Not only did he eschew all responsibility, but he also blamed the workers for it, attributing the blaze to “workers’ carelessness” and saying that maybe one of them had “not put out his cigarette before throwing it.”

On July 10, police arrested Hashem, his four sons, and three factory officials and charged them with murder. While the arrests brought plaudits, familiar questions began to resurface: What happened during the fire? Who caused it? Who is to blame?

Monitoring groups that inspected the factory after the fire believe that once the fire started, the factory became a death trap. The investigating agencies, Fire Service and Civil Defense, the Department of Inspection for Factories and Establishments (DIFE), and the Department of Explosives among others, all concluded that the factory’s construction and operation were littered with violations.

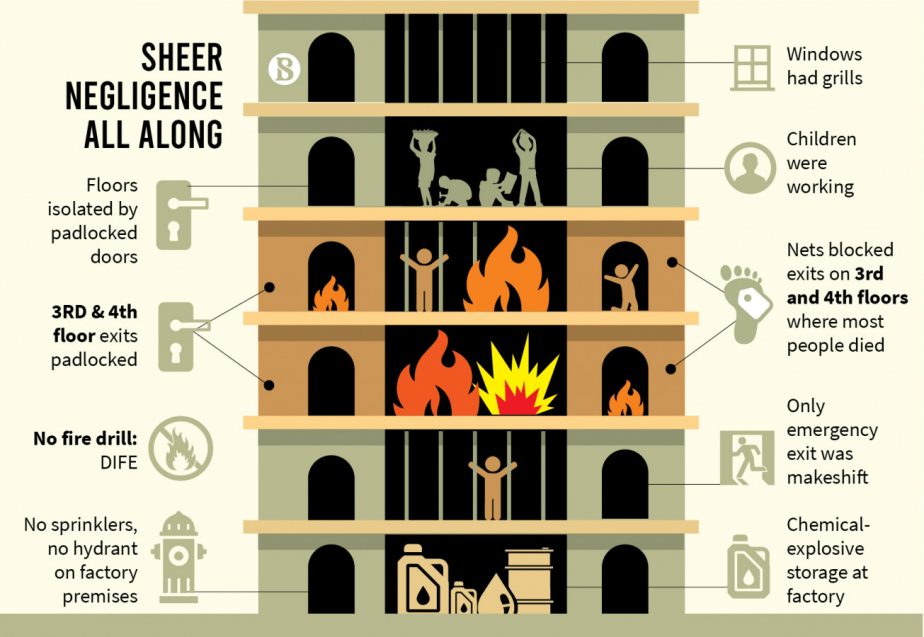

The fire broke out in a six-story building within the factory’s vast compound. The flames are believed to have originated on either the third or the fourth floor. Preliminary investigation found that each floor was isolated from the others using padlocks. So, when the fire broke out, the only exit point was already blocked. A worker could not go downstairs to find safety, nor could he go up to the roof to meet the fire rescue teams.

Credit: The Business Standard

The windows were blocked by burly metal grills. Instead of four staircases for entry and exit, a requirement under the law, the building had two staircases, of which only one was usable. There were no sprinklers or exhaust fans in or around the building. Ironically, Sajeeb Group is an importer of fire extinguishers, but the factory did not seem to have one.

During a visit to the spot, Mohammad Monzur Alam, vice president of the Electronic Safety and Security Association of Bangladesh, told The Diplomat that he wasn’t sure if fire extinguishers would have helped either. “I don’t think the workers had even been trained to use fire extinguishers,” he said.

In addition to all the flagrant violations, the building was being used as a factory and as an illegal storage space for chemicals as well. At the very least, storing chemicals requires proper licensing and Sajeeb Group’s factory did not have one. The carnage at Narayanganj was indeed a classic case of both wanton negligence and ineptitude. However, it is not the first of its kind.

Since 2005, Bangladesh has seen at least nine major industrial fires, including the one at the Sajeeb Group’s factory. Of these fires, at least four involved the improper storage of flammable chemicals.

In 2010, Dhaka woke up to the worst fire it had ever seen. After a transformer burst near a residence in Nimtoli in Old Dhaka, the flames began to spread. Fanned by lackadaisical monitoring of nearby chemical factories, the fire went on to consume 124 lives. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina herself went to the spot to oversee rescue operation, cancelling all official engagements.

Two years later, a fire broke out at a textiles factory in Dhaka. The death toll was 112. In 2016, flames tore through a packaging factory in Dhaka’s Tongi, killing 36 people. In 2019, the Churihatta fire in Old Dhaka left 71 dead and brought back the same questions that were never answered – What happened during the fire? Who caused it? Who was to blame?

Credit: The Business Standard

Fire service data from early 2019 shows that at least 468 fire incidents took place in Old Dhaka’s Lalbagh, Hazaribagh, Sadarghat, and Siddique Bazar – home to more than 500 illegal chemical warehouses and factories.

Globally, it is often considered that the 2013 Rana Plaza industrial disaster, which claimed 1,134 lives, changed the face of industrial safety in Bangladesh. It reshaped the ready-made garment industry for the better; brands scrambled to improve safety and security in the 4,000-odd factories that produce their orders, and formulated a “gold standard” in labor reforms. Upon closer look, however, the factories protected by international standards are only a small speck of Bangladesh’s total.

In the eight years prior to the 2013 crash, upwards of 1,000 garment workers were killed on the job. After the collapse, brands reciprocated to global watchdog initiatives to increase the safety and security of workers under two binding remediation agreements, seating representatives of global brands and labor union leaders equally at the same table.

Most notably, the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh produced more than 100,000 safety improvements in 1,500 factories in its first five years. However, there remains a glaring lack of remediation in many factories working for big brands. For instance, 118 factories working for H&M still lack safe exits, 159 lack fire alarms, 163 do not have a sprinkler system installed, and 44 factories require immediate attention. Top decision-makers within H&M are constantly updated on the statistics, yet so many factories remain in poor working condition even after eight years.

The Accord’s alternative, which is poised to completely take over by August 2021, is a local regulatory body called the RMG Sustainability Council (RSC), which is already predicted to be less effective by many reports on account of being non-binding for both suppliers and brands. In the absence of the Accord, experts fear that factories will revert to non-compliance and sweatshop-like conditions, since this is cheaper and more profitable.

Perhaps the Narayanganj industrial fire will serve as a timely and ominous litmus test of how efficient local regulatory bodies can be.

Big brands have already shown minimal interest to extend or call on the government to find binding replacements to the Accord. At the heart of this reluctance lies a pernicious cycle. Laborers throughout the country have been historically forced to accept low wages without any comprehensive interventions by stakeholders to fix wage structures. As it stands, 60 percent of the profit lands in the coffers of people who have no role in the manufacturing process; 35 percent goes into materials and transport, and roughly 1 percent makes it to the workers.

Brands lobby the government and suppliers to keep wages as low as possible. Suppliers and industry organizations in turn corner the government, insisting that low wages keep local suppliers globally competitive.

In H&M’s case, it promised “fair living wages” to 850,000 workers across the globe in 2013. By 2018, H&M changed its tone and resorted to improving “wage management systems,” which failed to register any visible impact. In this race-to-the-bottom, industrial workers in Bangladesh suffer the deepest impact despite their best efforts to increase wages from $68/month in 2013 to $96/month in 2020.

Pocketing the lion share of profits, one would expect big brands to ambitiously pursue workers’ safety, and ensure that suppliers make radical changes in their factories. Yet, workers are still forced not only to accept low wages, but work through pandemic lockdowns and internalize their realities as their irreparable and inescapable fate.

In a month, no one will ask what happened during the Narayanganj fire, who caused it, and who was to blame. No one will remember Mina Akhter or Swapna Rani as anything more than industrial fire casualties, just another statistic. Truly, the subaltern cannot speak.