A North Korean oil tanker pulled up to a Chinese port in April this year, the such first recorded visit in nearly half a decade, after Pyongyang eschewed traditional trading methods in favor of sanctioned, difficult to trace ship-to-ship transfers at sea.

The North Korean-flagged Sin Phyong 2 (signaling its location under the name Songmyeng 2) visited the Chinese port of Longkou in the country’s northeast in mid-April, staying docked at the Chinese port for several days before signaling its journey back to the DPRK’s western coastline.

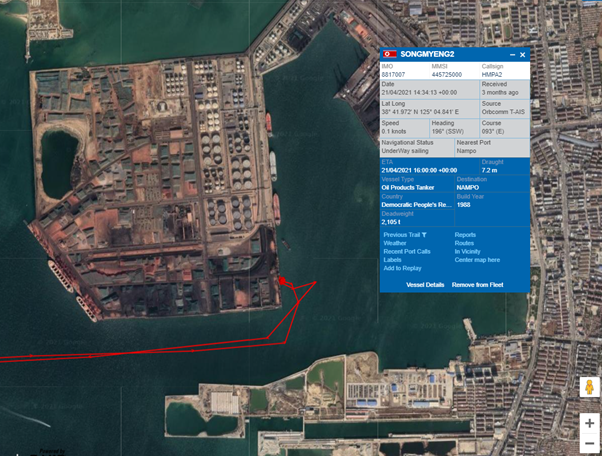

Although satellite imagery indicates that the ship was docked nearer to a bulk cargo handling facility, it was also just a short distance southward from a relatively large oil tank farm, where oil tankers are frequently visible in commercially available satellite imagery.

With oil exports to North Korea under United Nations Security Council (USNC) restrictions, any oil loading onto the North Korean tanker could potentially constitute a breach of U.N. resolutions, unless the UNSC were notified of the shipment and that overall shipments to North Korea remain below an internationally agreed threshold.

The Sin Phyong 2 / Songmyeng 2’s visit to Longkou Port on April 20. Oil storage infrastructure is visible to the north (satellite image does not match the date of the vessel visit). Image courtesy of Pole Star Space Applications.

Slick Trade

Once regular visitors to nearby Chinese and Russian ports, North Korea’s oil tankers began to disappear from Auto Identification System (AIS) tracking systems in mid-2017.

As international pressure mounted on Pyongyang in the wake of successive weapons tests, the UNSC begin limiting oil exports to North Korea, placing a cap on total annual imports and reporting requirements on the exporters.

But it did not take long to find the North’s missing tankers, with combinations of vessel tracking data and aerial and satellite photography showing that Pyongyang had changed its oil import patterns, conducting the trade at sea between vessels.

Pyongyang also appears able to persuade opportunistic oil traders to deliver directly to its Nampho oil terminal on the country’s west coast, which North Korea has been steadily expanding, despite the international restrictions that should have truncated trade to only a fraction of pre-sanctions levels.

Numerous governments, the U.N. Panel of Experts (PoE), and think tanks have all noted that these methods allow North Korea to far exceed the U.N. mandated cap on its oil import business.

Most of North Korea’s oil tankers have been sanctioned by the United Nations for violation of these resolutions, which should prohibit them from entering foreign ports, but Pyongyang has also been busy violating a different set of sanctions, which prohibit the purchase of new vessels.

The North Korean-registered tanker that visited China in April is once such recent addition to the country’s tanker fleet, with North Korea acquiring the ship in August 2019.

Prior to its acquisition, the PoE had already highlighted the vessel’s role as a ship-to-ship transfer vessel providing oil to its North Korean counterparts at sea, while sailing under the name Tianyou and flagged to Sierra Leone. But with a new North Korean registration and free of a U.N. designation, the Sin Phyong 2’s roles could feasibly include direct imports from foreign ports.

According to tracking data from the Pole Star Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) platform, after a long period of non-broadcasting the ship began moving around the Korean Peninsula in 2020.

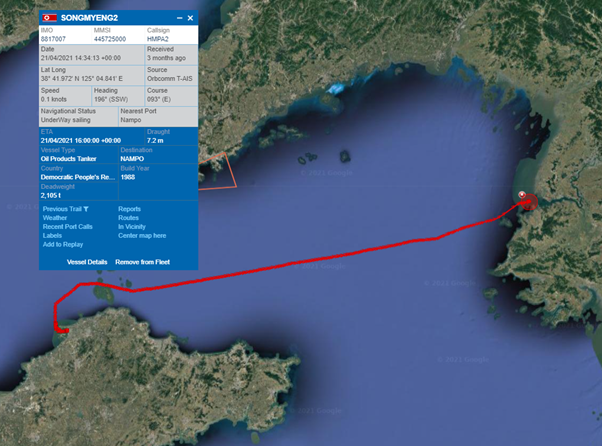

This year, the ship has visited one of North Korea’s favored ship-to-ship (STS) transfer zones near Shanghai in addition to the trip to Longkou. The latter journey was first time a North Korean tanker broadcast such a visit to tracking systems since Washington began designating the North’s tankers in 2017, according to the Pole Star platform.

Although it is not possible to ascertain the direction of the trade from satellite imagery alone, it seems unlikely that North Korea would be exporting oil products to neighboring China. The country has no domestic oil and gas production and limited refinery capacity and has traditionally been heavily dependent on its neighbors for its energy needs.

The Sin Phyong 2 / Songmyeng 2’s journey back the North Korea following the visit to Longkou Port. Image courtesy of Pole Star Space Applications.

Sanctioned Status

As is the often the case with North Korea sanctions enforcement, whether an oil product transfer to the Sin Phyong 2 breached the U.N.’s restrictions likely comes down to a matter of interpretation.

According to the 1718 Committee website, which tracks reports of oil shipments to North Korea, no U.N. member state recorded an oil export to North Korea in April. China reported a small export the month prior, its first such report since September 2020, though perhaps the website has yet to be updated for more recent transfers.

The March shipment is the only reported oil transfer to North Korea so far this year, which the U.N. assesses to be equivalent to 0.98 percent of the agreed 500,000-barrel cap.

In this circumstance, given that the reported totals of oil transfers are so low, it would be possible to make the case that any transfer onto the Sin Phyong 2 would remain well below the U.N.-allowed threshold and subsequently not breach U.N. sanctions.

Yet in their most recent report published in March this year, the U.N. PoE noted that in 2020, North Korea exceeded the U.N.-mandated cap on oil imports by “several times the annual aggregate” of 500,000 barrels per year.

Given the relatively large volumes of illicit oil already flowing into North Korea via prohibited methods, it may also not be difficult to make the opposing case that any transfer to the Sin Phyong 2 would also be a violation of U.N. resolutions, if the illicit transfers have already reached the U.N.’s annual threshold.

The Sin Phyong 2’s continuous broadcasting, however, is unusual and may lend weight to the idea that Beijing and Pyongyang are (unsurprisingly) leaning toward the more lenient interpretation of the U.N.’s resolutions, though many North Korean vessels behave similarly in Longkou port, indicating that the waters are too busy to attempt such “dark” visits with any regularity.

Although North Korean oil tankers have not broadcast their locations in Chinese ports for years, the New York Times reported in March that a tanker called New Konk visited a different port along the country’s south eastern coast on January 1, 2021. The New Konk is not registered in North Korea and has been identified by the U.N. Panel of Experts as a ship-to-ship transfer vessel, with the PoE recommending the ship for U.N. designation and a global port ban.

Other North Korean tankers and coal smugglers also routinely visit Chinese waters along the country’s southeastern coast, with ship tracking data and the PoE indicating that not even the Pyongyang’s strict COVID-19 measures were not enough to greatly stem the flow of North Korea’s smuggling operations in 2020.

Beijing has typically been truculent with the U.N. Panel of Experts when asked about the large-scale sanctions evasion occurring on its doorstep, indicating that perhaps enforcement of the U.N.’s restrictions is not currently a priority, and the Sin Phyong 2’s arrival in the Longkou may be the next data point in this currently downward trend.