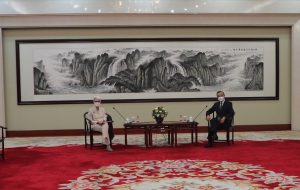

U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman visited the Chinese city of Tianjin at the end of July for high-level talks with Foreign Minister Wang Yi, alongside other senior Chinese officials, in which “frank and open discussion about a range of issues, demonstrating the importance of maintaining open lines of communication between [the U.S. and China]” were conducted, according to a State Department readout.

Same, Same, But Different

The conversations yielded little in terms of substantive commitments and specific policies – though both parties notably registered their appreciation for the vigorous, at times heated and contentious, exchange of views. Senior diplomats in Washington saw the trip as a critical hedge against existing tensions spiraling into vitriolic, full-on confrontation; the foreign policy leadership in Beijing, on the other hand, viewed it as a prime opportunity to air long-standing grievances in a candid and comprehensive manner.

Much of the commentary thus far has sought to emphasize the absence of significant shifts in policies and stances from either party. Comments have ranged from castigating China for ostensibly waging a “propaganda war” during Sherman’s visit in pursuit of its ongoing campaign of revanchist nationalism, to the view that the “arrogant attitude” of Washington yields “low expectations for outcomes from Sherman’s visit.” Such polarizing reviews are undergirded by a singular point of convergence: The existing bilateral skepticism and mistrust between China and the United States has fundamentally molded the reception and perception of the talks in a direction that is not conducive toward de-escalation, nor more comprehensive mutual understanding.

Yet it is equally imperative to retain a sense of perspective. Sherman’s visit came amidst some of the most turbulent and acrimonious times in contemporary history for the bilateral relationship. From the stiff tariffs and rancorous economic decoupling measures introduced by former President Donald Trump and maintained by President Joe Biden, to Washington’s insistence on assembling alliances in an effort to contain the spread of Chinese global influence, to spats between Chinese and Western diplomats over topics ranging from Huawei and the treatment of Chinese scholars and students in the U.S., to what Beijing deems as blatant interference with its “domestic affairs,” it is clear that cooler heads have yet to prevail in the Beijing-Washington dyad. Trust and perception of “the other side” are at an all-time low, with polls revealing substantial animosity among Americans and the Chinese toward their counterparts across the ocean.

When read in this light, Sherman’s visit may have achieved less than it had set out to, yet was still remarkable and offered a potentially critical window for a reset of bilateral relations. Policymakers from both sides of the Pacific would benefit from seizing upon the opportunity to delineate clear boundaries to China-U.S. competition, identifying room for positive collaboration, and minimizing unnecessary misunderstandings and misrepresentation, which would only be to the common detriment of both parties.

The Case for Chinese Optimism

Could there be grounds for the Chinese to be optimistic about the U.S. approach to bilateral relations? Biden’s victory last November initially spurred many in China – especially internationalists and liberals open to deepening mutually beneficial, symbiotic ties between the two largest economies in the world – to view a normalization of bilateral relations as being on the table. Yet Biden’s subsequent rhetoric, specifically his castigation of China as a “rival” with which competition would be “extreme,” rendered many disillusioned and pessimistic over the prospects for a more compassionate and open China policy.

Sherman’s visit was clearly insufficient to overturn or negate the many fundamental forces pushing for a more hawkish China policy in Washington: the economic rivalry and technological competition, the clash of ideological values and cultures, and Biden’s need for a foreign policy agenda that can unite the country. Yet it did amount to an olive branch, and there are several reasons that Chinese policymakers ought to take note of it.

First, as the highest-ranking official to visit the country from the Biden administration thus far, Sherman’s visit reflected Washington’s awareness that it needs to swiftly clear the air and manage the surging resentment toward U.S. foreign policy that had accumulated swiftly in China only six months into Biden’s tenure. As the second-most senior diplomat in the U.S. administration, Sherman’s status compounded the significance of her visit. It suggested that, notwithstanding the burgeoning bipartisan consensus on China, the United States remains keen on keeping communication channels open among the highest echelons. With that said, the tardiness with which the visit was orchestrated, and Biden’s persistent reluctance to meet with President Xi Jinping, certainly reflects the increasingly hard-line attitudes toward China in Washington.

Second, Sherman unambiguously declared that the United States did “not seek conflict” with China. She emphasized the vital importance of maintaining an overarchingly cordial relationship between the two countries, as well as exploring means through which sustainable competition – as opposed to altercation or destructive rivalry – could be maintained. The U.S. delegation additionally raised the need for ring-fencing and firewalling critical issues of contentions from areas of cooperation, a point that was echoed by Beijing, which noted the importance of bilaterally negotiated rules of engagement. Sherman’s comments reflect a subtle yet significant departure from earlier rhetoric espoused by Washington. While what she said by no means contradicted previous statements by Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, the focus was distinctively placed upon managing, as opposed to amplifying, divergences.

Third, the visit saw the United States commit to an expanded range of areas in which collaboration between the two states are – at least in principle – tenable and necessary, ranging from climate change to public health operations to counterterrorism. There were also attempts on the part of the U.S. diplomats to address Chinese grievances on matters concerning Iran, the Korean Peninsula, Afghanistan, and Myanmar. Sherman affirmed the view that collaboration was not an option but rather a practical requirement in the face of global challenges.

None of this would convince a diehard anti-American skeptic that the United States is open to negotiations, compromise, and collaboration. Yet for others, the above suggests that a glimmer of hope remains and that the expressed goodwill should be harnessed by the Chinese in carving out more room for pragmatic consensus-brokering and resolution of disagreements.

The Case for American Optimism

On the other hand, Washington should equally recognize that Beijing remains far more open to (limited) concessions and (carefully embraced) substantive convergence than is often credited by mainstream commentary on the Chinese administration. The Chinese issued two lists at the recent talks – one concerned the “wrongdoings” that the United States had allegedly committed; the other concerned “individual cases” with which China was concerned. For all the fanfare and bombastic rhetoric associated with them, and subsequent backlash, the demands featured on these two lists were, in fact, relatively modest in ambition and moderate in kind. In lieu of fundamental and radical lifting of economic tariffs and protectionism, senior Chinese diplomats called upon their American counterparts to “unconditionally revoke […] visa restrictions over [Communist Party of China] members and their families, revoke sanctions on Chinese leaders, officials, and government agencies,” as well as pledging to support Chinese students and enterprises within the United States. None of this amounted to attempts at compromising the any core interests or values, or, indeed, exporting Chinese authoritarianism abroad.

While official press releases in Beijing remonstrated Washington for its “condescending contempt over ideological models,” they also acknowledged Sherman’s earnestness and openness in seeking common ground. Characteristically trenchant spokesperson Zhao Lijian noted that the Chinese administration saw the talks with Sherman as “profound, candid, and helpful” in enabling a “better understanding of each other’s position.” One may rightfully view this as mere lip-service and public relations; yet, in juxtaposition to the far harsher words uttered by many of his colleagues toward other nations, it is apparent that the Chinese response was comparatively subdued.

The relatively toned-down rhetoric in Beijing’s official response to the diplomatic exchange, coupled with Xi’s earlier calls for a “more lovable China,” are indicative of the growing awareness among the senior party leadership of the need for China to adjust course, without foregoing its baselines and vital interests, in its foreign policy. As much as the newfound modulation and implicit moderation in Chinese rhetoric are implicit at best and difficult to spot, it behooves international actors to recognize that the Chinese administration is by no means a monolith, and that moderate voices could and should prevail – and will if only given the opportunity to.

Finally, the observation that Beijing had adopted an abrasive, confrontational tone in addressing Washington might well be empirically valid, yet the question that ought to be asked, then, is what spurred it? Some could posit that the Chinese government is innately aggressive, expansionist, revisionist, and imperialist. Yet a more pragmatic and reasonable interpretation would be that China – as it always has over the past century – views its gestures, speech, and behaviors as rightful responses to foreign provocation and interference. Sherman’s visit demonstrated that U.S. critique and commentary on China’s “domestic affairs” can be measured, calibrated, and targeted as opposed to invoking structuralist explanations that cast the Chinese state as diametrically opposed to the United States’ interests. For those in the United States who do not wish to see a new boogeyman constructed out of China, the approach adopted here may well offer a viable modus operandus – one in which criticisms are made, but not at the expense of practically advancing reforms and changes that benefit both the United States and China.

Two Pitfalls Ahead

The above has highlighted reasons why those seeking a return to normalcy in bilateral relations should indeed be optimistic. Yet it must concurrently be acknowledged that the road ahead is by no means a smooth trek and features numerous pitfalls that, if mismanaged, could easily reverse the precious little that the Sherman visit has accomplished.

First, there is the question of perceptions. Many among the ruling classes and intelligentsia in China view the United States to be an arrogant hegemon in decline, one that would lash out and weaponize non-existent issues as “talking points” with which to bury China. In particular, the “tone” and language employed by U.S. diplomats has become a growing issue of sensitivity and offense in the eyes of nationalistic Chinese citizens. While Sherman’s recommendations were by no means invasive, they remained controversial and imperialistic in nature in the eyes of many in China.

Similarly, the American portrayal of Chinese requests has grossly exaggerated both the force and demanding nature of the lists. Some have sought to use these lists as evidence to demonstrate that attempts at concessionary dialogue and discussion with the Chinese are impracticable despite the fact that many of the demands involved remain legally and politically feasible. The assertive demeanor with which these propositions were communicated clearly did not help, but it is vital for observers to separate the signal from the noise.

Second, on the subject of interests: Perceptions are only one half of the story. As Sherman and Wang both acknowledged, there exists a vast spectrum of problems that require joint efforts from Washington and Beijing in order for genuine mitigation or resolution. There is more that unites China and the United States among their interests than divides them – or rather, at least that is still the case for now.

What would be rather worrying, then, is if economic and political decoupling between the two states results in a continued de-linkage in interests, culminating eventually at a world where the zero-sum game mentality championed by fervently anti-China or anti-U.S. politicians comes to prevail over common sense. Common sense, of course, would unambiguously suggest that positive-sum, win-win collaboration between the two countries is critical for global stability and genuine development.

Whether Sherman’s visit enabled both sides to have a fair chance at articulating their visions and concerns remains to be seen. One thing is more certain: There needs to be more in-depth, rigorous, and targeted dialogue between the U.S. and China.