Recently, numerous commentaries have been published arguing that the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) could or should have done more in response to the February military coup in Myanmar. ASEAN is also accused of not updating its organizational principles to respond more effectively to contemporary security challenges, while some say the Myanmar coup may have fractured the bloc’s cohesiveness.

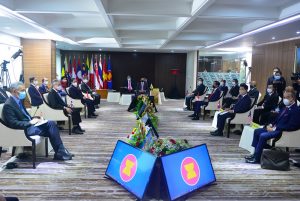

Since the coup, some ASEAN leaders have engaged in a whirlwind of meetings, including with Myanmar’s military junta, resulting in ASEAN releasing a Five-Point Consensus in April, laying out its first steps for resolving the Myanmar crisis. Although the military junta has not been overly receptive to the Five-Point Consensus, it has just recently announced that it will hold an election in about two years.

Nonetheless, a better strategic historical understanding of what ASEAN is, and more importantly what ASEAN is not, will indicate that most of the recent outcries about ASEAN’s response to the Myanmar coup have been misplaced.

Like the proverbial phoenix rising out of the ashes, ASEAN picked up where the Association of Southeast Asia (ASA) left off. ASA was established, but largely failed, to prevent two diplomatic rows: the Konfrontasi between Indonesia and Malaysia, and a territorial dispute between Malaysia and the Philippines. When the Malaysian Federation was formed in 1963 consisting of Malaya, Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore, its formation was strongly opposed by Indonesia’s President Sukarno, which viewed it as a British strategic move to contain Indonesia’s geopolitical ambitions in the region.

The Philippines also opposed the formation of Malaysia, claiming parts of Sabah and breaking off diplomatic relations with Kuala Lumpur. Sukarno launched a Ganyang Malaysia, or “crush Malaysia,” campaign, using propaganda and later an undeclared war known as Konfrontasi to disrupt Malaysia’s formation. Konfrontasi lasted until May 1966, when Indonesia under its new leader Suharto decided to explore diplomatic options in ending the Konfrontasi, resulting in a peace treaty in August 1966. The Philippines later rebuilt diplomatic relations with Malaysia later, although it has never formally relinquished its claim to Sabah.

Against this tense strategic backdrop, ASEAN was formed in 1967 with the aim of reconciling relations among three of its five pioneer members – Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, and Philippines – and serve as an important confidence building platform. ASEAN originally focused on discussing cooperation in socio-economic-cultural activities and pledged a strong adherence to the principle of non-interference in member states’ internal affairs.

Since the end of the Cold War, ASEAN has increased its membership to include every Southeast Asian nation except East Timor; Myanmar was admitted in 1997. ASEAN has also broadened its security and economic engagements to encompass multiple forums and platforms, including the ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting (ADMM), ASEAN Political-Security Community (APSC), and ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (AFTA). It also expanded its multilateral mechanisms outside its region by connecting with external powers such as the United States, China, Russia, Japan, and Australia via the ASEAN Regional Forum, ASEAN+6, ADMM+, and numerous other multilateral platforms. At the same time ASEAN has signed a few free trade agreements as a bloc with other economic blocs and other states.

ASEAN’s main focus of security dialogues usually touches on cooperation in mitigating non-traditional military issues such as international crime, transboundary pollution, humanitarian disaster assistance and relief, and cyber security. Some of these dialogues have been translated into meaningful actions but usually take a long process for ASEAN to deliberate and decide based on its consensus-based form of decision-making.

The core principles that make ASEAN unique – non-intervention in the internal affairs of its members and consensus in decision-making – are crucial in sustaining the organization. While ASEAN has been accused of being paralyzed by these principles and described as a “talk shop,” it must be pointed out that these principles have been the price of keeping all its members in.

The ASEAN member states have mixed historical experiences, which required a common set of principles to ensure every member is willing to sustain its membership of ASEAN, and to ensure the regional body’s cohesion. ASEAN member states are characterized by a wide range of regime types, including monarchic, democratic, authoritarian, and communist systems. Except for Thailand, all of its members were former colonies of Western powers and have gained their independence since World War II. As a result of decolonization and creation of new states with sovereign territories, some of the ASEAN members have overlapping boundary issues, and a few of its members have gone through tumultuous nation building processes, often suspicious of their neighbors’ strategic intentions. Hence, the allaying of covert interference by regional neighbors via ASEAN’s principle of non-interference is a sacrosanct tenet for keeping the region stable and preventing conflicts erupting among its members.

The military coup in Myanmar was not the first that ASEAN has experienced. For example, in the last two decades, Thailand has had two coup d’etats, in 2006 and 2014. As a response to the most recent of these coups, ASEAN released an official statement urging all parties to resolve the crisis peacefully through dialogue. The Thailand coup was later resolved internally. Any tougher pressure against Myanmar’s junta today might attract accusations of double-standards by ASEAN. Indeed, what ASEAN has committed to in its recent attempts to resolve the current Myanmar coup is much more dynamic and tenacious than its response to past coups in Thailand. Hence, despite strong calls for more resolute ASEAN actions to alleviate Myanmar’s post-coup crisis, ASEAN should not be expected to do more than what it is capable of or willing to do.