Chinese firms have been strongly encouraged to focus on working for the common prosperity, focusing on social value. Many firms are toeing the line in order to avoid regulatory entanglement down the road. After all, the crackdown on the technology sector in recent months has been mainly geared toward protecting consumers and reducing the sway of large firms.

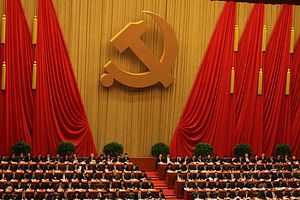

China remains a Communist nation. This means that, even though China is instituting regulations that are not entirely dissimilar to those in the West, the regulatory environment is much more concentrated and potent than in the United States and Europe, and is in some areas ideologically led. How can investors make sense of this?

After a slew of regulations rocked the technology, education, and online insurance sectors in recent months, firms have been scrambling to ensure that they are contributing to the common prosperity. Firms have engaged in a wide variety of endeavors, from investing in poverty alleviation to donating funds for COVID-19 relief. The founders of Meituan, Pinduoduo, Xiaomi Corp, and others have donated large amounts recently to social causes, in the hopes that they will be viewed more benevolently by regulators.

Even more pointedly, President Xi Jinping recently called for stricter “regulation of high incomes,” which includes the ultra-high earnings enjoyed by internet and other firm founders. Netizens voiced concerns over what constitutes “high incomes” and how it would be redistributed. Some experts view charitable contributions, rather than higher taxation, as the most ideal channel for this redistribution. So far, the focus has been placed on reducing large income differences in the form of regional gaps, urban-rural gaps, and income gaps in order to promote common prosperity.

The idea of common prosperity is not a new one in China. It was first advocated for by Mao Zedong in his 1953 “Resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on the Development of Agricultural Production Cooperatives.” The idea is to eliminate human exploitation and absolute poverty. Deng Xiaoping also followed the concept of common prosperity, but allowed for the fact that some would get rich first, while others would follow.

Now that many people have gotten rich, Xi has revived this ultimate goal of socialism. Xi wrote in a statement issued by the Communist Party’s Central Committee for Financial and Economic Affairs, “We can allow some people to get rich first and then guide and help others to get rich together … but we must also do our best to establish a ‘scientific’ public policy system that allows for fairer income distribution.”

Does it work? Assistance from the private sector helped to achieve China’s poverty alleviation goals. According to data from the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce, by June 2020, there were 109,500 Chinese private enterprises taking part in the poverty alleviation program “Ten Thousand Enterprises Helping Ten Thousand Villages,” which helps poor households through industry and employment. According to the federation’s data, over 15.6 million poor individuals had benefited from the program.

The “common prosperity” ideology has resulted in an increasing number of regulations to protect the Communist Party’s vision of the common good and induced self-correcting behavior among Chinese billionaires and large firms. It is the realization of Chinese socialism imposed upon market-based, modern activity, which makes it especially hard for investors to interpret. In contrast to regulation in the West, which simply seeks to curb practices that can destabilize market efficiency, Chinese regulation aims to inject a sense of fairness into economic practices. This “fairness” is viewed through the lens of the Communist Party, and particularly through the eyes of Xi Jinping.

Under Xi, China is marking the evolution of its socialist market economy from a poor society to a thriving economy with “common prosperity.” This does not involve the typical evolution of firms and wealth as seen in the West, but has produced some awkward bumps along the road in the form of regulation and now wealth redistribution via voluntary charitable donations.

Chinese experts have increasingly expounded upon the idea of common prosperity in the media, while Chinese firms scramble to join in the ideological edification. Whether China’s flourishing private sector can continue to grow under such a heavy hand has yet to be seen. If it does, this will, indeed, give great credence to the idea of common prosperity.