A bearded young man stares at a foreign passport, searching for a visa to the now obsolete Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. A white flag bearing the shahada, the Islamic oath, flutters over the border crossing in Hairatan, which from August 15 has marked the northern frontier of the new Islamic Emirate.

The man puts a stamp on the first page of the passport, the one that should remain blank. He doesn’t know how to scan the traveler’s bag so he opens it and meticulously goes through its contents. He makes up for his lack of experience with a smile and wishes the travelers a good trip in broken English.

Calm chaos are the best words to describe the situation in Afghanistan one month after the Taliban takeover.

The withdrawal of foreign forces, a hasty evacuation of foreigners and thousands of Afghans fleeing to safety after the fall of Kabul was followed by procedural chaos and nationwide confusion. No one knows how harsh the new rulers will be. But everyone knows that the old days of relatively relaxed social and political relations are gone.

A poster of now former President Ashraf Ghani, ripped. Photo by Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska.

With the chaos, however paradoxically, also came order. For many years it was impossible to cross the country by land. Taliban checkpoints in places outside of the government’s control were potentially dangerous and road crime was common. Now, crossing the country has become easier than ever.

The distance between Hairatan and Kabul is 450 kilometers, but passing over the old, poorly maintained roads, the journey can take more than 10 hours. Drivers now make sure to switch off the music before they approach the few Taliban checkpoints on the way. As one Taliban commander said, music does not have to be officially banned. People already know it’s a sin.

Most checkpoints can be passed with relative ease. Although the Taliban are not present on all the roads in the country, traveling has become much safer. People know that despite the absence of clear new rules, the punishment for any wrongdoing will be harsh.

But as Alamamed Amiri, 26, a traffic policeman in central Kabul, tells me, the police are no longer allowed to give fines, which, he argues, the Taliban deem haram, forbidden by Islam. Unlike many other policemen in the country, he decided to continue working under the new government. The Taliban promised not to take revenge against the traffic police for serving Kabul’s former government.

While the new government has promised a national renewal in the spirit of Islam, it needs the institutional memory, procedures, and staff of the former republic to run the country. Many administrative employees have decided to stay in their positions and continue serving under the new rulers.

Without them, the whole state system would fall into disarray.

Alamamed Amiri, the traffic policeman in central Kabul. Photo by Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska.

Watching city life from the streets can provide important insights into the changes within Afghan society.

“The streets are less crowded and nothing is functioning properly,” Amiri says. “The elites are gone but average people have stayed. The streets are safer. People are afraid of the Taliban. There are much less women outside too.”

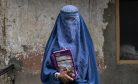

While official rules on female garments are still unclear, women know what the return of the Taliban means for them. Despite the resistance by social media activists who have been posting pictures in traditional Afghan dresses bearing the hashtag #donttouchmyclothes, street fashion reflects fear rather than rebellion. Faced with the unknown, many women choose to stay at home.

Others are hastily updating their closets. Hamida Karimi, a 28-year old dentist, walks around one of the shopping malls in central Kabul, her beautiful, self-assured face contrasted with the black, shapeless abaya and burgundy hijab she is wearing. She looks for conservative outfits that would fit the new unwritten rules, though she shops without much enthusiasm.

“I’ve always worn shorter clothes, not longer than above the knee. It was comfortable and I could walk in the streets on my own, even in the evening. Now I only travel by taxi. I’ve heard that I could be attacked or insulted so I have to buy new clothes. It’s never happened to me but I’ve heard such stories,” Karimi says.

“I used to study German but I have recently quit the course because co-education is no longer allowed. I could attend a group with women only but we’re all scared. I now study online.”

Karimi decided to continue working, however, as she did not want to abandon her patients. But work has changed, too. She can no longer run the clinic together with her male business partner and only accepts female patients. She was not forced to make this move – she did that, she says, for her own security.

“There have been no good changes in the past month. The banks are closed, local administration and ministries too. We don’t know who are the people in the interim government. Children are afraid to go to school and are scared of the men with weapons. I cannot sleep at night because of nightmares.”

Karimi wants to leave as soon as she can, but opportunities to do so are scarce now. Thousands of Afghans are looking for an opportunity to leave the country. The destination is not an issue, as long as wherever they end up is not under strict Taliban rule.

Murtaza Sultani, 19, has been trying all the different ways to escape, so far to no avail. For the past two years he has run a barber shop in central Kabul. He made a great effort to design the interior, which is now fully covered in wood with quirky capes bearing the image of the U.S. flag. Before the coming of the Taliban, he had around 20 customers a day; now only two or three. Since the Taliban ban trimming beards, people stopped frequenting his shop.

Murtaza Sultani in his barber shop. Photo by Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska.

“People are afraid. The Taliban have already gone to a few shops run by my friends and said they should stop trimming beards and cutting people’s hair in Western styles. I’m not afraid of the Taliban but work is difficult, I worry about the business. We pay $500 in rent a month and we cannot afford it,” says Sultani.

Sultani is an ethnic Hazara and he does not have facial hair, which may also become a problem in the future. He may soon have to close his business. The nearby shop selling DVDs has already closed.

In the past month, Kabul has lost some of its former charm. The murals highlighting social problems, corruption, and women’s rights that were spread across the city are now gone, replaced by religious messages. A few murals are still left, but it is clear that they will soon fall into oblivion and so will the old tricolor flag. The white shahada is becoming ever-present. It is the main product offered by street sellers these days.

But not everyone is worried about the coming of the Taliban. Wazir Mohammadi, a 23-year old banana seller from Kapisa, says that since the Taliban takeover, street crime has decreased.

“I was happy when the Taliban arrived in Kabul. Earlier, it was full of thieves stealing my bananas and money. I was robbed three times. Now it’s safe,” he says.

There are downsides to the new system, however.

“In the past I could earn up to 10,000 Afghanis a month. Now it’s around 5-6,000. People don’t want to buy more food, there is no work, people don’t have money and don’t want to leave their homes. Everything has changed after the Taliban took power.”

It is unclear how long the economic crisis will last. Drought has displaced thousands and there’s a fear that Afghanistan will soon face food shortages. Much of Afghanistan’s $9.5 billion in foreign reserves are located outside of Afghanistan. The funds are frozen and banks have put in place withdrawal limits of $200 per week. Government employees have not been paid for the past three months. Afghan markets are full of people selling their belongings.

It is also unclear what course the Taliban will take in the longer term. Home searches have already begun, protests have been banned, and gender segregation in schools imposed. Several local journalists were severely beaten by the new police. But for average people, and foreigners, the Taliban have so far been lenient.

Young bearded men have appeared on Kabul’s streets, streets they have never known before, whose life and vibe they do not understand. Many of them came from the provinces; others had been released from prisons only weeks before. Spotting a Talib does not prove hard in the capital. Long hair and untrimmed beards, traditional two-garment clothes, turbans or small caps with a cut in the front are their characteristic signs.

They patrol the streets in large Jeeps inherited from the Afghan and U.S. armies with large flags attached to them. But many of them just enjoy the city. They frequent zoos, amusement parks, and public places; they take selfies, relishing their newly gained power. Watching them, one cannot help the feeling that the main divides within Afghan society have been not only religious and ethnic, but also of class. The boys, most of them poorly educated, who grew up outside of big cities, are now in charge and they want to get to know their new capital.

Taliban fighters also frequent the now empty prisons, opened at the onset of the fall of Kabul. Some of them served time behind the bars, others visit out of interest.

Qudratullah Nazim in Pul-e-charkhi prison. Photo by Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska

Qudratullah Nazim spent 10 years in the notorious Pul-e-charkhi prison in Kabul. He walks through the corridors with a group of Taliban and his memory floats back to the days of his detention. He admits that he killed people. Originally from Kandakhar, he commanded a group operating in Kabul, Helmand, and Kandahar. His brother went on a suicide mission and Nazim is proud of him. The whole family is.

“They attacked our country in 2001, they were brutal, bombed wedding halls, madrassas, and mosques. We were only defending our land, our people and our religion,” he says.

His time in custody was hard. He remembers very well the torture he was subjected to: spraying with tear gas, electroshocks, beatings. Now Nazim enjoys coming back to the prison, visiting his old cell. He is free, but the place will remain an important part of his story – and Afghanistan’s history – forever.

Nazim is proud that the Taliban have defeated the enemy. He cannot explain, however, what kind of legal system will replace the old order.

“We will introduce Islamic law,” he says. “We don’t focus on the punishment but crime prevention. We will try to prevent corruption and if someone commits a crime we will punish only them, not their whole family like the previous government.”

Crime prevention under the Taliban has so far proved successful. The nation lives in fear. But whether the new rulers can govern and control the country remains to be seen — just like the true face of the new Taliban.

Taliban members visiting the Pul-e-charkhi prison. Photo by Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska.