The phrase “free and open” has become a code phrase for “U.S.-aligned,” notably when used to describe the Indo-Pacific region. There are some obvious connotations.

To those who would imagine another Cold War (or a Cold Peace) vis-à-vis China, the connotation is to the “free world” of the earlier Cold War.

To those who would look instead back to the history of China and the region, the connotation is to the “open door” policy of the United States at the turn of the 20th century.

To those who would prefer to believe in a European (or Euro-Atlantic) ideal of nearly a century later, the connotation is to a continent “whole and free.”

None of these connotations applies easily today to the vast region known as the Indo-Pacific. There are different nations with governments that may be classified according to their varying degrees of political, cultural, and economic freedom, which is often and increasingly seen differently in the eye of the beholder. There is no longer a door to be held open, as the United States understood its role a century ago, predicated upon a failed Chinese state sitting atop a vast Chinese market. Today, China is in full control of the hinges. There is no clear belief in a single or “whole” Indo-Pacific region. Rather, there are multiple subregions across the Pacific and Indian Oceans that have never and probably never will consider becoming one unit.

So, what does “free and open” really mean there?

To give its promoters the benefit of the doubt, it may mean something more than being aligned with the United States. What it could and ought to mean is a large region with great economic and human potential being accessible to the entire world – to its investment, interaction, and understanding.

As for its societies, they too may be free and open in the Western, ideological sense, but almost certainly only if the former condition holds. That is, a region – any region – can be neither free nor open if it is not at peace with itself and with the outside world. The same holds for any of its constituent parts.

All that is pretty straightforward, theoretically. The problem today in the Indo-Pacific – a region defined thus largely by outsiders – is that those same outsiders are joining together with nations in the region to establish a rather different geopolitical environment.

That environment is based not on the concept of a free and open regional community but instead on something resembling a geopolitical chessboard in which a ring of non-Chinese relationships would nominally serve the causes of freedom and openness by constraining, obstructing, and otherwise limiting Chinese power, namely its military power.

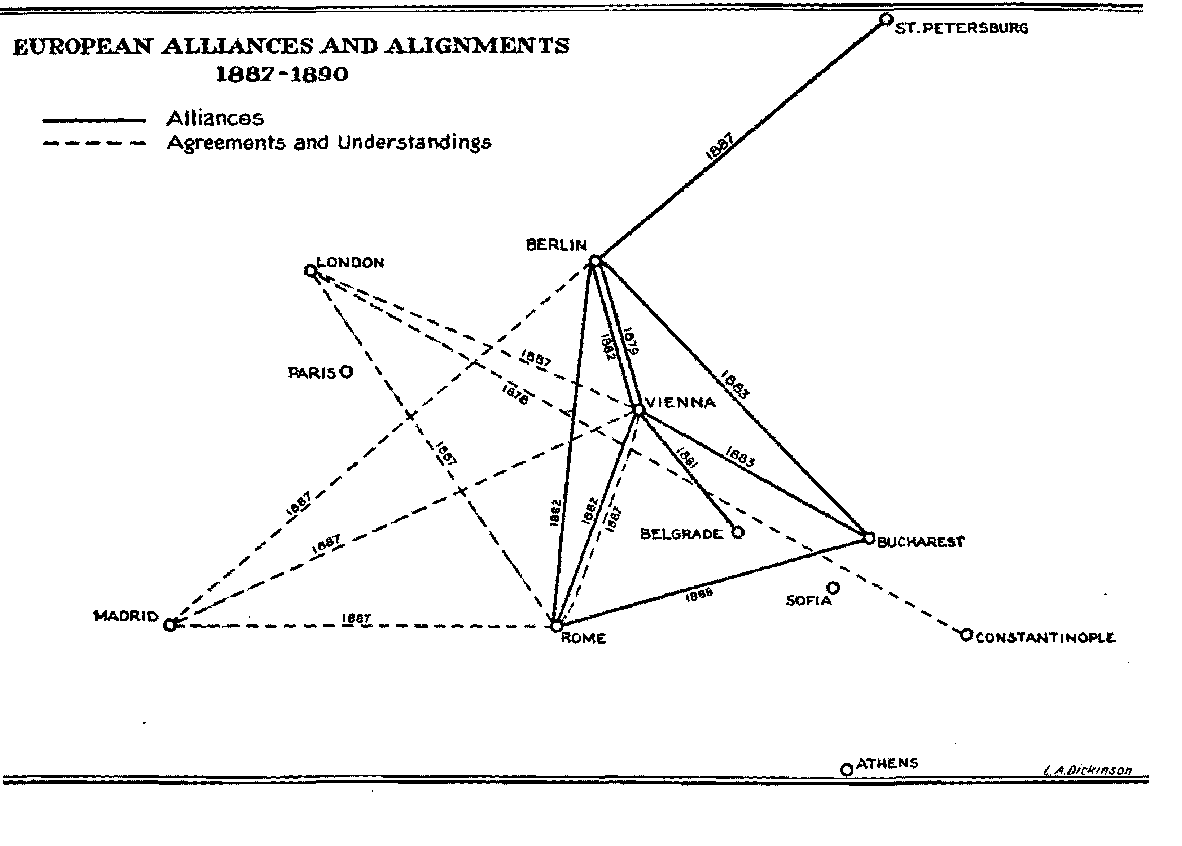

The prevailing concept or model therefore is not Woodrow Wilson’s “new diplomacy,” which called for open covenants and communities of power, but rather the old diplomacy of Europe in the era of high imperialism. Back then, the European order, such that it was, was based on a set of overlapping informal and formal relationships, and a tenuous and largely imaginary “balance of power.” This is one illustration of just how tenuous it was:

From William L. Langer, European Alliances and Alignments, 1871–1890 (New York, 1931).

It is not historically accurate to say that this complex system led directly to the breakdown of the European order and the Great War, but it would be fair to say that the latter probably would not have come about if the former had not itself failed.

The basic system now being established in the Indo-Pacific appears to place the United States in the role of Germany in the above illustration. The priority for imperial Germany, and the principle on which the entire set of relationships was based, was the need to keep France and Russia from creating their own anti-German alliance. The priority for the U.S. today seems to be to keep China from creating any sort of alliance with any of the other major powers in its region – with the possible exception of Russia.

Germany ultimately failed to forestall the “fateful alliance” of France and Russia. Today China is busy creating multiple alignments and alliances in trade and investment, which will probably matter much more to its regional and global role than the military and industrial balance of power being pursued by the United States.

As to that balance of power, it should also be said that it requires a closed, not an open, system in order to exist (if it ever really does exist), whereas a security community may be as closed or as open as its members wish. The more peaceful and adaptable communities, such as those in the Western Hemisphere and in Europe, have historically been, or have sought to be, open.

A free and open diplomacy for the Indo-Pacific region therefore needs to align itself with the politics and economics of the early 21st century, not the late 19th. A set of military alliances and alignments may otherwise lead to the exact opposite result that its planners say they want.