On September 16, China formally applied to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) an 11-member trade bloc touted as setting “a new standard for trade and investment in one of the world’s fastest growing and most dynamic regions.”

Commerce Minister Wang Wentao submitted an application to New Zealand, the repository state of the CPTPP, the Chinese ministry announced Thursday.

Notably, the CPTPP – then known simply as the Trans-Pacific Partnership – was originally brought to the finish line under the leadership of U.S. President Barack Obama. But his successor, Donald Trump, immediately withdraw the United States from the deal, leaving the remaining 11 members counties scrambling to reconfigure the pact.

China’s bid for membership drove home the intense irony: A grouping originally designed to advance U.S. leadership in trade now has Beijing looking for membership while Washington is on the outside.

When China submitted its official membership application, it made good on years of hints from Chinese leadership. Despite longstanding perceptions of the bloc as “anti-China,” member countries have always insisted that the CPTPP “is an open and inclusive Agreement and we welcome like-minded parties to join.” Likewise, China has made frequent vague expressions of interest. At the November 2020 APEC Summit, President Xi Jinping said China would “favorably consider” joining the CPTPP. Less than a year later, Beijing has made its membership bid official.

Global Times, the famously hawkish state-owned tabloid, said the application cements Beijing’s “leadership in global trade” and leaves the United States “increasingly isolated.”

The reality, though, is far more complex. For one, China is exceedingly unlikely to actually be able to join the CPTPP. The agreement by design includes high standards that go far beyond tariff removal, including regulations guiding market access, labor rights, and government procurement.

In theory, China could accept the CPTPP’s more stringent provisions as a necessary condition for joining. Some analysts, particularly within China, have argued that this would be a way to jump-start China’s own difficult domestic reforms; a similar dynamic played out in the lead-up to China’s WTO entry.

However, some of the CPTPP’s requirements will challenge the Chinese Communist Party’s insistence on tight state control. For example, the higher standards for labor rights in the CPTPP forced reforms in Vietnam, which overhauled its labor code to recognize workers’ rights to form independent unions. Given China’s repeated crackdowns on independent labor organizations, Beijing is unlikely to be willing to follow Vietnam down that path. Likewise, the CPTPP’s relatively strict provisions on subsidies to state-owned enterprises, “free flow” of data, and opening government procurement deals to foreign competition will challenge China.

Japan, the CPTPP chair this year, has already signaled some reluctance. Economy Minister Nishimura Yasutoshi told reporters that “it’s necessary to determine whether China… is ready to meet [the CPTPP’s] extremely high standards.”

There have been some suggestions that China is looking to dilute these high standards through its membership process – or, more colorfully, “gut the CPTPP from the inside.” But it’s unclear whether the other CPTPP members would agree to that. There may not be much demand to dilute the CPTPP to fit in China, simply because the nearly all of the bloc’s members already have trade deals with Beijing.

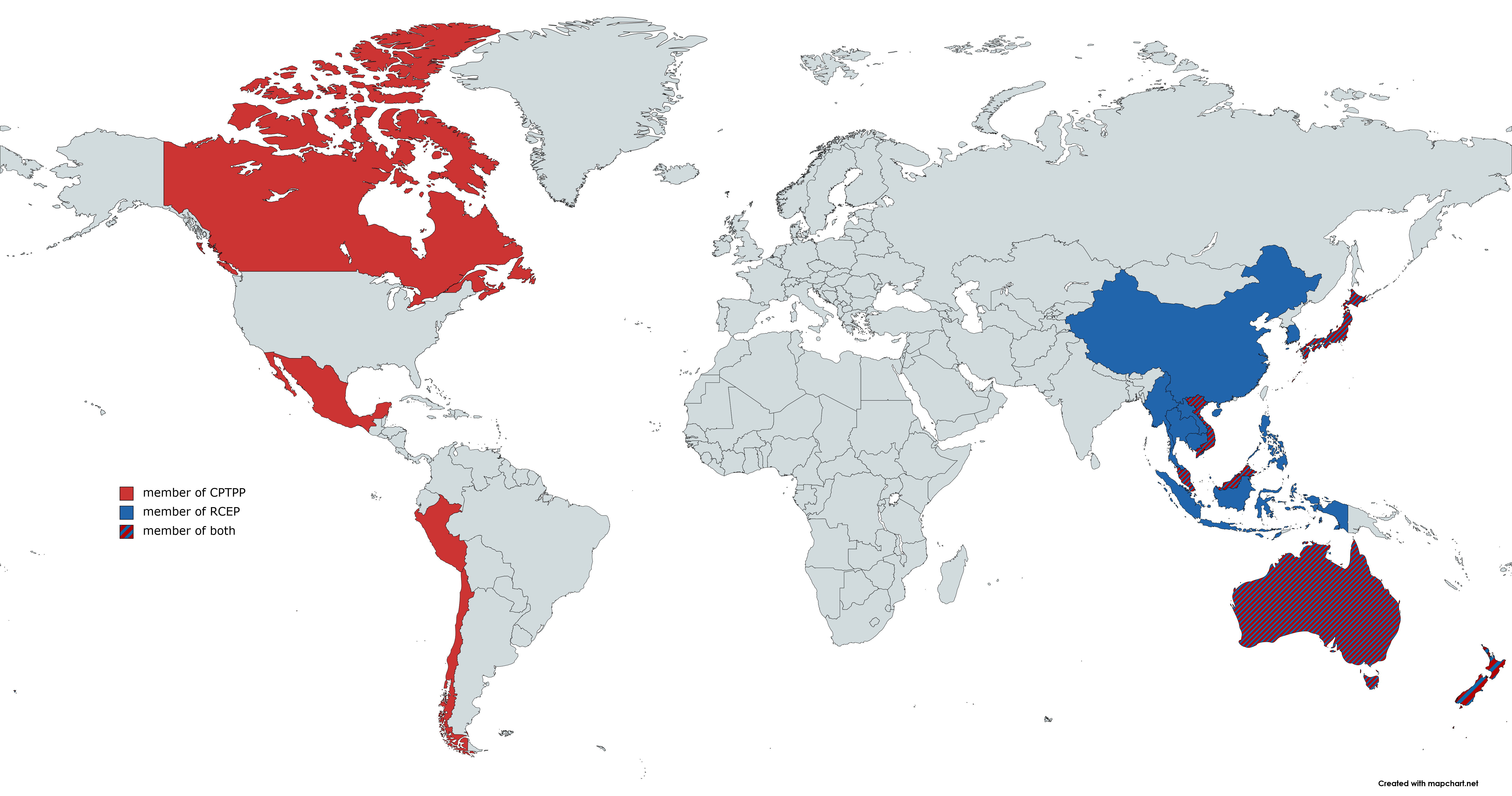

There is a great deal of overlap between the CPTPP’s membership roster and members of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), another recently concluded mega-trade pact that includes China. CPTPP members Australia, Brunei, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, and Vietnam all effectively have a free-trade agreements with China via RCEP, and thus they may not have much appetite for reconfiguring the CPTPP to shoehorn China in. Likewise, Chile and Peru both already have bilateral FTAs with China.

That leaves just Canada and Mexico, and they have their own issues with China joining the CPTPP. The U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), renegotiated under the Trump administration, contains a “poison pill” clause, requiring any of the three members to notify the others should it wish to enter into trade negotiations with a “nonmarket economy.” Any of the other partners could then unilaterally withdraw from USMCA. Many observers – including Chinese state media – believe the clause was explicitly designed to prevent Canada and Mexico from signing an FTA with China, and thereby giving Chinese goods an easy back-door into the United States. It’s not entirely clear yet how that clause would apply to multilateral trade negotiations, but it will give Canada and Mexico pause when considering China’s CPTPP membership.

Given the major hurdles to China joining the bloc, it’s likely that its CPTPP application will be pending for a long time coming — and possibly forever. There’s some symbolic value to the application, as China can point to its bid as proof of its commitment to free trade and multilateral arrangements. But if China isn’t actually willing to do the work required to join, that symbolism will quickly fade away.

China isn’t the only option for the CPTPP to expand its ranks. The U.K. is also in talks to join the bloc; Indonesia, the Philippines, South Korea, and Thailand have all expressed interest in joining as well. Taiwan is also keen to join and has questioned China’s qualifications for the bloc. On the other hand, the United States has not made any moves toward rejoining the pact, even under the new Biden administration.