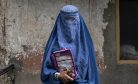

With a Taliban announcement expected soon on a new government, women in the western city of Herat took to the streets in protest. Many worry that the Taliban’s 21st century rule in Afghanistan will resemble its brutal 1990s regime, under which women were kept out of schools, were all but absent from public life, and entirely absent from government.

Although Taliban leaders and spokesmen have said that women will be allowed to work under the Taliban’s government, they give such statements with a key caveat as demonstrated by Zabihullah Mujahid, the Taliban’s spokesman, at a press conference in August (emphasis added):

The issue of women is very important. The Islamic Emirate is committed to the rights of women within the framework of Shariah. Our sisters, our men have the same rights; they will be able to benefit from their rights. They can have activities in different sectors and different areas on the basis of our rules and regulations: educational, health and other areas. They are going to be working with us, shoulder to shoulder with us. The international community, if they have concerns, we would like to assure them that there’s not going to be any discrimination against women, but of course within the frameworks that we have. Our women are Muslim. They will also be happy to be living within our frameworks of Shariah.

One need only look at the broad range of Muslim societies in the world to appreciate that context and interpretation matters. The Taliban’s ideology has long had little space or use for women. It’s no surprise that Afghanistan’s women — arguably the most educated cohort of women in Afghanistan’s history — are concerned what Taliban rule will mean for them.

In late August, Fawzia Koofi, a former member of the Afghan Parliament, said that women “like men, should be involved in all the affairs of the country.” She encouraged women to be unified and push for their rights: “I think Afghan women need to be more unified than ever. No one will give them their rights easily. They have to be unified, they have to guarantee they have a presence, and it is not acceptable that they are sitting in the corner of their houses and monitoring the situation.”

On September 2, women gathered in Herat calling for women’s representation in the future Afghan government. According to TOLO News, their banners included statements such as: “No government is sustainable without women’s support. Our demand: the right to education and the right to work in every aspect.” Others carried signs saying, “Don’t be afraid, we are together.”

Ahead of an official announcement, the deputy head of the Taliban’s political office in Qatar, Sher Abbas Stanikzai, responded to BBC questions about the shape of the future government. While saying that it would be “inclusive,” referring to Afghanistan’s ethnic groups, he wavered on the matter of women holding top posts. He said there “may not” be a place for women in the cabinet or in any other top positions.

A recent report from Reporters Without Borders (RSF) claimed that of 700 female journalists in Kabul, only 100 are still working a mere two weeks after the Taliban takeover. “Of the 510 women who used to work for eight of the biggest media outlets and press groups, only 76 (including 39 journalists) are still currently working,” the report stated.

While some female journalists have continued to work, many have been harassed or pressured to cease doing so in the days since the Taliban takeover. What’s happened with Afghanistan’s female journalists will arguably apply also to women in other professions: Even if there is no “official” barring of women from the workforce, the official and unofficial rules and pressures on those who continue to work may become too great.

In late August, Taliban spokesman Mujahid urged women to stay home — temporarily — because the group’s fighters “are not trained” to interact with women. Women should stay home, he said, to ensure that they are not “treated in a disrespectful way… or God forbid, hurt.”

This, of course, puts the onus on women to suffer for what are ultimately the failures of men.