In 2020, Shamsia Alizada, the daughter of a coal miner from Kabul, received the highest score out of 170,000 students in the annual national university entrance exam. In a country full of grim news, news of Alizada’s achievement brought happiness to many. Alizada’s success came at an important time for the country as the government engaged in talks with the Taliban on a possible peace deal in Doha. Her success made it into news programs and spread on social media like wildfire. Government officials, civil society, journalists, and social media users intensely covered her success, positioning it as part of the argument for the Taliban that women’s rights and their active participation matter, and women have to be considered and their rights taken seriously. The Taliban did not let girls go to school or allow many women to work under their rule from 1996 to 2001.

Education has long been held up as a shining example of Afghanistan’s reconstruction. Since 2001, after the overthrow of the Taliban, the international community has invested billions into the education sector in Afghanistan.

Over the last two decades, Afghan women had great opportunities to improve their lives in many areas, including education. By 2018, girls made up almost 38 percent — 3.8 million — of students in the country; by comparison only 5,000 Afghan girls were enrolled in schools in 2001. Not only has the enrollment of girls in school increased over the last two decades, but the presence of women in higher education has also risen.

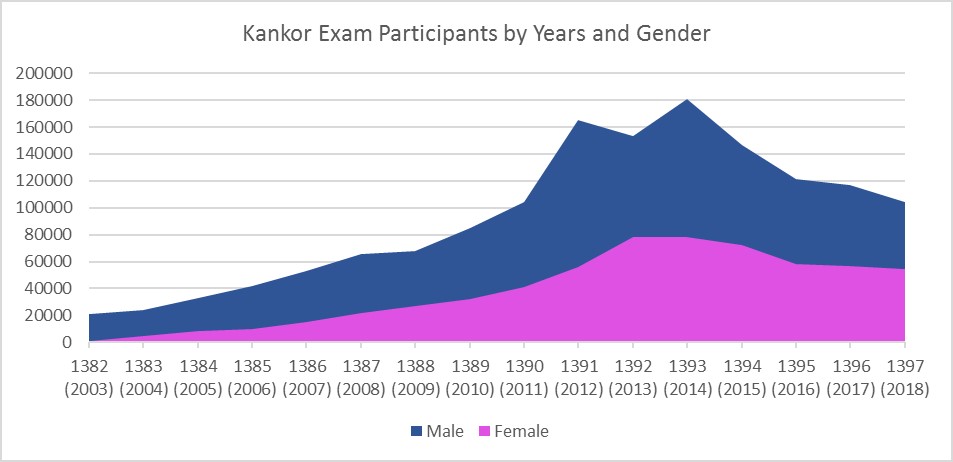

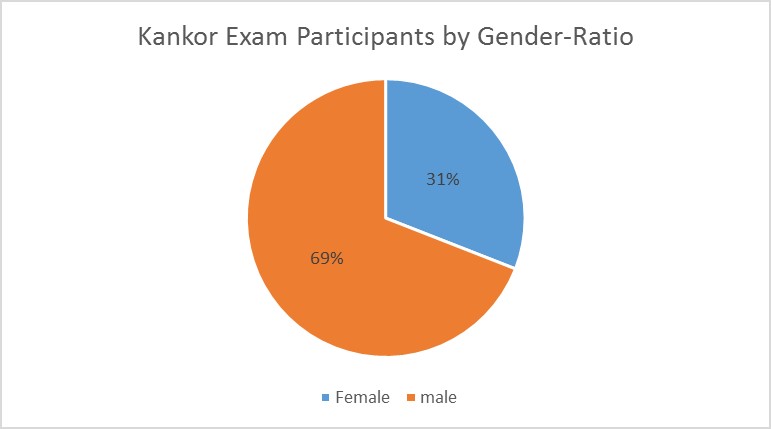

Datasets from Afghanistan’s national entrance exam, called Kankor, show that the number of female participants in the Kankor examinations has gradually increased in the last 20 years. The statistics from the Kankor datasets also illustrate the persistent wide gender disparity in higher education. But a steady rise in female participation in the exam seemed promising.

Figure 1: Students’ participation in the university entrance exam since 2003. Data from the author’s own compilation based on the Kankor dataset.

According to statistics from the Ministry of Higher Education (MoHE), the gender disparity in higher education enrollment decreased over time in favor of female students entering Afghan universities. For example, there were only 1,000 female participants in the Kankor exam in 2003, while this number jumped to an all-time high – 78,000 – in 2013.

Figure 2: Gender breakdown of participation in the university entrance exam (2003-2018). Author’s own compilation based on the Kankor dataset.

As figure 1 shows, however, the number of male participants in the Kankor exam has always exceeded that of female participants on the national level. But this is not true in some provinces in Afghanistan. For instance, Herat witnessed a reversal, with the number of female participants in the exam coming to exceed that of male participants. This change of participation in a highly traditional society where abundant hindrances exist for female education is phenomenal.

According to the Kankor datasets from the National Examination Administration (NEXA), in Herat province the participation of female students in the national entrance exam made up 44 percent compared to 56 percent for male students in 2008. This gender disparity, however, gradually narrowed. Figures from 2019 indicate that female participation in the Kankor exam in Herat rose to 53 percent, while for males, it declined to 42 percent. Thus, Herat province represents a true success story for female education in Afghanistan. In Afghan society, reversing these gender gaps is a remarkably unprecedented feat.

But these gains are now at risk. Even before the collapse of the Afghan government in mid-August, numerous reports indicated that Afghanistan’s education system was sliding backward and becoming crippled by poverty, increasing insecurity, and a lack of investment in infrastructure and trained staff.

During the last few years, with the deterioration of the security situation in the country, the government of Afghanistan pumped ever more funds it into the security and defense sectors. Last year, the Ministry of Higher Education communicated through an official letter to all public universities across the country that the government would need to withdraw $10 million from the ministry’s development budget to be channeled into the defense and security sectors.

For years, the education sector has been crippled by security challenges. Those challenges, after the Taliban takeover, seem to be superseded by ideological setbacks.

An audio clip recently circulated in the WhatsApp groups of Afghan faculty members suggests that the Taliban leaders in Herat province have instructed public and private institutions of higher education to stop allowing girls to sit with the boys in the same classrooms.

A three-hour discussion involving university professors, the owners of the higher education institutes, and Taliban leaders argued there is no alternative for maintaining co-education of girls and boys. The Taliban leaders also argued that male teachers could not teach female classes. The higher education sector already has an extreme shortage of female faculty members and lacks the infrastructure to accommodate male and female students in completely separate classes.

Under the previous Afghan government, violence and instability prevented many women and girls from accessing schools and education. In contrast, now it is the attitude of Taliban leaders toward female education that will gravely impact the enrollment of female students and their opportunities for success.

A bittersweet coda: The NEXA announced the results of the annual national exam for 2021 on August 25. Again, a female student, 20-year-old Sulgai Baran from Kabul, topped the Kankor exam out of 179,930 total participants. In a deep irony, Sulgai is a Pashto language name that means “cry” in English.