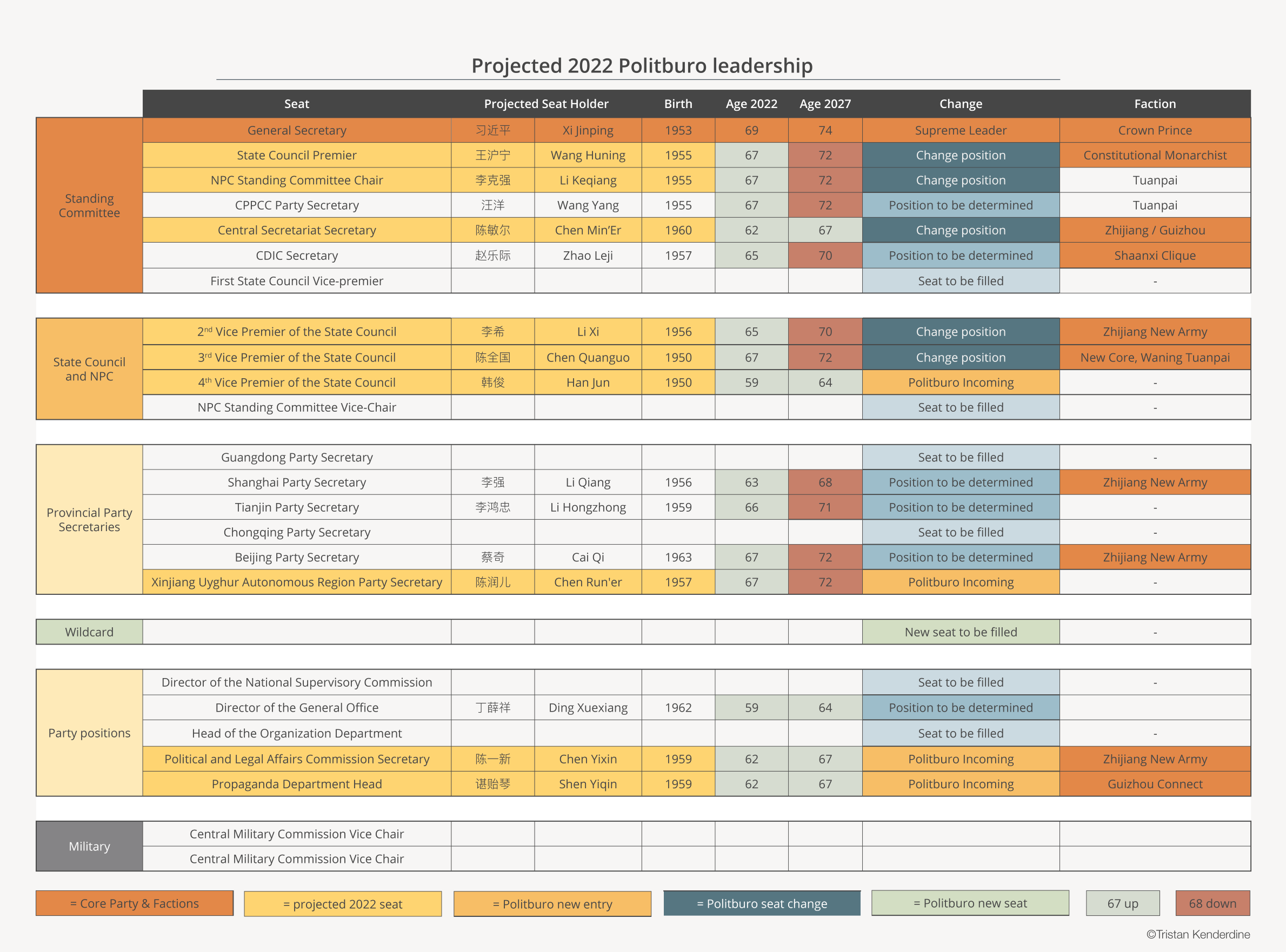

Many positions within the Chinese Communist Party’s Politburo are institutionally organized as permanent seats. But individual politicians may hold multiple seats, opening spaces for both new seats to enter Politburo and for skillful politicians to carry on in their existing seats.

At the 20th CCP Congress, Yang Jiechi is set to retire as director of the General Office of the Central Foreign Affairs Commission. The natural successor would be State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi, but Wang is also already over retirement age. Without a standout candidate to inherit China’s nominal foreign policy leadership, it is likely that the foreign affairs Politburo position will be scrapped in 2022.

With both Yang and Wang retiring, the highest state-ranked foreign affairs cadre would likely be one of the incoming five state councilors, who would nominally take over the state foreign policy portfolio, or an incoming minster of foreign affairs. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, though, actually has very little remit over foreign policy in China. Even nominally, whomever emerges as minister of foreign affairs will only be stepping into the second-ranked state position, and will be far down the CCP pecking order. Real foreign policy has always been made in Party Leading Groups, which have only become more centralized under Xi Jinping’s system of commissions.

The reality of creating a new Politburo seat is that a strong political candidate will carry the seat into creation. If foreign affairs falls out of Politburo, a new party position could then take up a Politburo place. The five most likely options are: an internal security state councilor position refashioned into a near-abroad foreign policy chair; the United Front Work Department director; a new Spiritual Civilization Office director; an empowered Policy Research Office director; or a new vice president.

With the foreign affairs portfolio state councilor seat dropping out of the Politburo, the obvious replacement would be to install the internal security/near abroad policy portfolio in its stead, remembering that internal security had been a Politburo Standing Committee position until 2012. There is a clear emerging need in elite party policy-making for a balance between near-abroad, domestic foreign policy narratives, ethnic affairs, and geoeconomic policy.

An inspired move toward a stronger police state-foreign policy hybrid in China could see Zhao Kezhi’s current state councilor position be made a Politburo place. Through the second Xi term, Zhao has acted like a Politburo member, and his internal security policy seat is the type of position that a third Xi term would need: a combined oversight of the domestic security apparatus and near-abroad national security foreign policy architecture, embodied in a CCP loyalist. Whomever inherits Zhao’s seat could be very quickly within the inner circle.

Elevation of the United Work Front Department Director is also an option, Sun Chunlan was in this seat in the first Xi term, and from an institutional perspective, the United Front Work Department director rejoining the Politburo would suit the 2022 state of political play. The United Front Work Department fits the policy portfolio of needing someone to take care of China’s bordered allies, Shanghai Cooperation Organization states, and domestic ethnic affairs agenda. But there is little talent young enough to proffer a good candidate, and these policy functions are more likely to be served within the upper party leading group structure. Current head You Quang is too old to be in contention and first-ranked deputy director Zhan Yijiong only just scrapes in under age restrictions. Other leadership contenders at United Front are also quite dusty, with deputy directors Bagatur and Xu Lejiang both born in 1955.

There was no foreign affairs Politburo position in Xi’s first term where Wang Huning held a Politburo place as Central Guidance Commission on Building Spiritual Civilization Office director. Wang continues to hold this important post, which defines the CCP’s place in the world – making Wang’s post arguably more powerful than any foreign affairs position. This Spiritual Civilization position is the ideological heart of China’s place in the world, constructing and disseminating civilizational values, state policy, and guidance for the highest-level party doctrine. Ecological Civilization, for example, was the guiding doctrine of Xi’s two terms and the CCP is overdue for a new civilizational signpost.

A strong institutional option would be to empower the Spiritual Civilization office director to the Politburo-yielding seat it was in 2007 and 2012, only falling out of the Politburo to accommodate Yang Jiechi at foreign affairs. However Wang Huning is the Spiritual Civilization intellectual architect and as he will remain in the Standing Committee, he will likely retain responsibilities as formal bureaucratic director of this party meta policymaking office. Another of Wang’s concurrent roles, though, was recently relinquished, resulting in the promotion of a new Policy Research Office director. The 62-year-old Jiang Jinquan would be a good candidate to ascend into the Politburo in 2022, particularly if Wang Huning were compelled to release some long-held policy responsibilities. If Jiang were eligible for two terms, he would be in strong contention; with only one term before he reaches retirement age, though, he is still good cover for what is essentially a push into a third term for an ideologically-driven regime, which might not make a fourth term.

Vice president would be the traditionalist position to occupy the vacant Politburo slot. However current Vice President Wang Qishan was installed in this seat precisely as a mechanism for him to avoid Politburo age restrictions. Reinvigorating the office of the vice president, a non-policy or governance specialist position, could give Xi another slot to place a well-rounded political ally. As vice president is currently a lame duck chair, and with the state in decline relative to the party, the ability to party-politicize this chair could be a strong Politburo wildcard move. However, with so many other pressing policy priorities to cover, the vice president returning to Politburo should be considered a low probability scenario.

The foreign affairs chair dropping out of the Politburo at a time of strong international friction would only signal that foreign policymaking is being absorbed by higher party functionaries, to be run more directly from the Central Foreign Affairs Commission, with only a figurehead spokesperson. While the Central Foreign Affairs Office director seat vacated by Yang Jiechi will become less important, it will not be dissolved and its responsibilities could be filled by a specialist spokesperson like Liu Xiaoming. By pushing state foreign policy offices and voices into groupthink, though, and by marginalizing any political faction right of Xi through the 2021 rectification purge, the foreign policy capabilities of the CCP in 2022 will only become even more limited and more of a policy liability for the administration.

Armed with little more than classical Leninism, some crudely imported Morgenthau realism, and with only a slightly better ability to project force than in previous decades, the types of deep policy layering necessary for China to achieve its diplomatic goals in international policy fields are unlikely to emerge from the next iteration of the Politburo.