The People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) air intrusions into Taiwan’s Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) have raised a lot alarm and encouraged unsupported claims about the rationale and purpose of these sorties. The most common claim suggests these flights are directed at Taiwan and constitute part of China’s broader “gray zone” activities against the self-ruled island. As I have opined elsewhere (see here and here), Taiwan is often only indirectly touched by these incursions, with most of the large-scale intrusions likely directed against the United States and/or formal U.S. engagement with Taiwan.

The most common incursion type has involved a single KQ-200 maritime patrol and anti-submarine warfare (MP-ASW) aircraft. The near daily presence of the KQ-200 denotes an operationally significant rationale, one that has little to do with Taiwan directly. Since entering service within the Eastern Theater Command in 2018 and the Southern Theatre Command a few years earlier, the aircraft has filled an important capability gap, providing the PLA Naval Air Force (PLANAF) a capability to persistently monitor foreign submarine and surface ship activity at or near critical maritime chokepoints and sea lanes of communication along the First Island Chain.

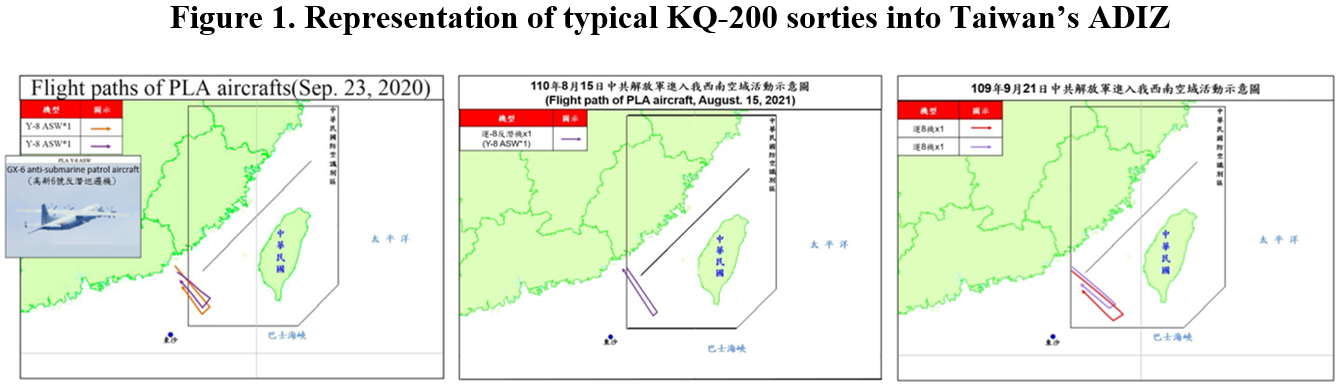

The KQ-200 has been involved in 70 percent of all incursions since September 2020. This makes the type the most common intruder into Taiwan’s ADIZ. Moreover, a close assessment of the KQ-200’s deployment patterns reveals some interesting details about the aircraft’s mission and incursion rationale. Based on pattern analysis of the type’s ADIZ incursions over the past two years, the KQ-200 is typically recorded loitering over the same geographic location roughly half-way between the major port city of Kaoshiung in mainland Taiwan and the Pratas Island, as illustrated in Figure 1. This raises some interesting questions about the sortie rationale.

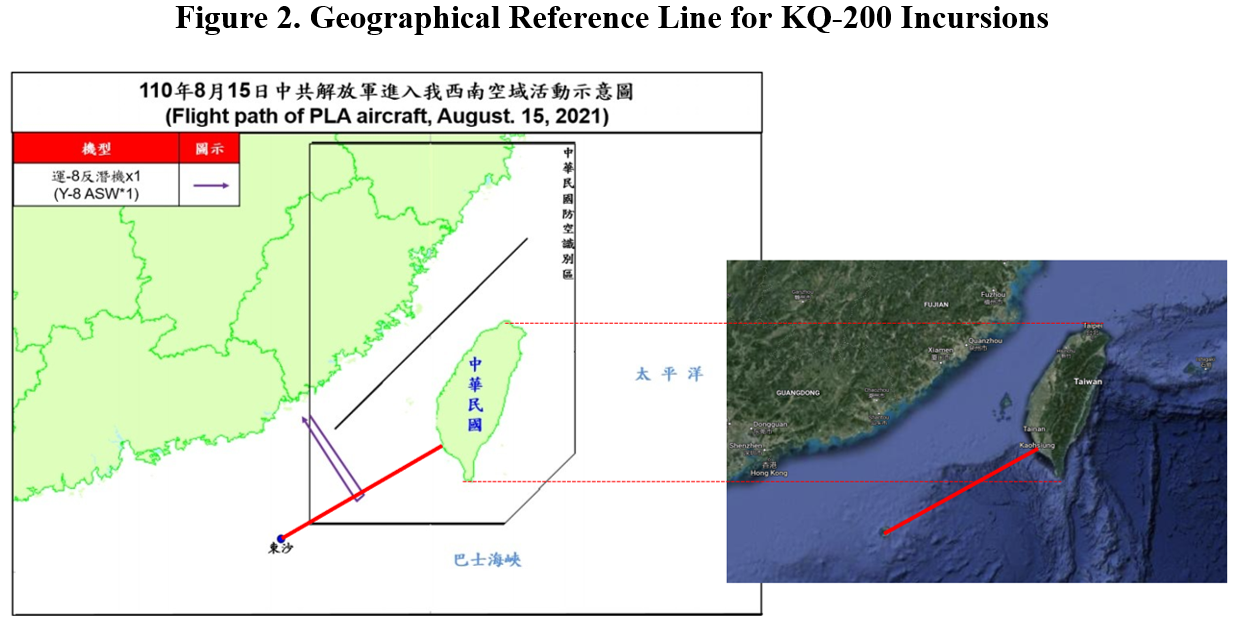

Using this sortie pattern as the basis, we can draw a straight line between the city of Kaoshiung and the Pratas Island as a reference point for further analysis (see Figure 2). Using this as a reference, Figure 2 also illustrates the same line against a satellite image from Google Maps, providing us with a more useful geographical reference point for analysis.

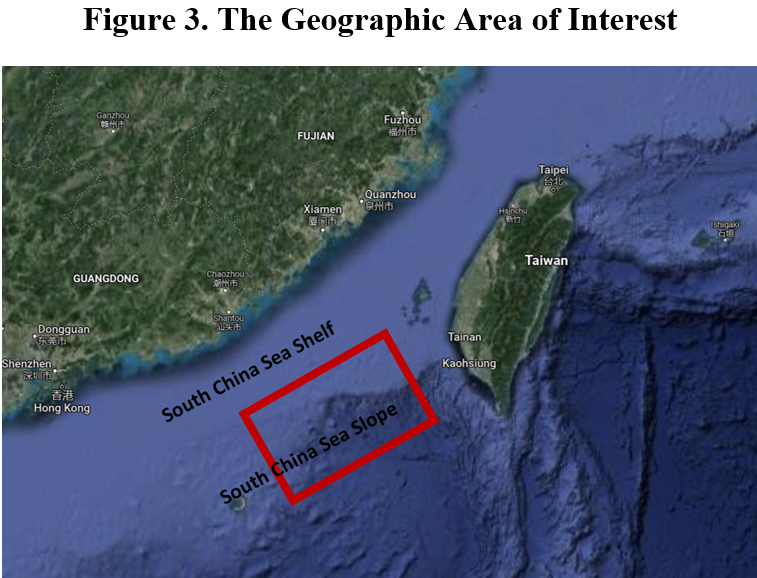

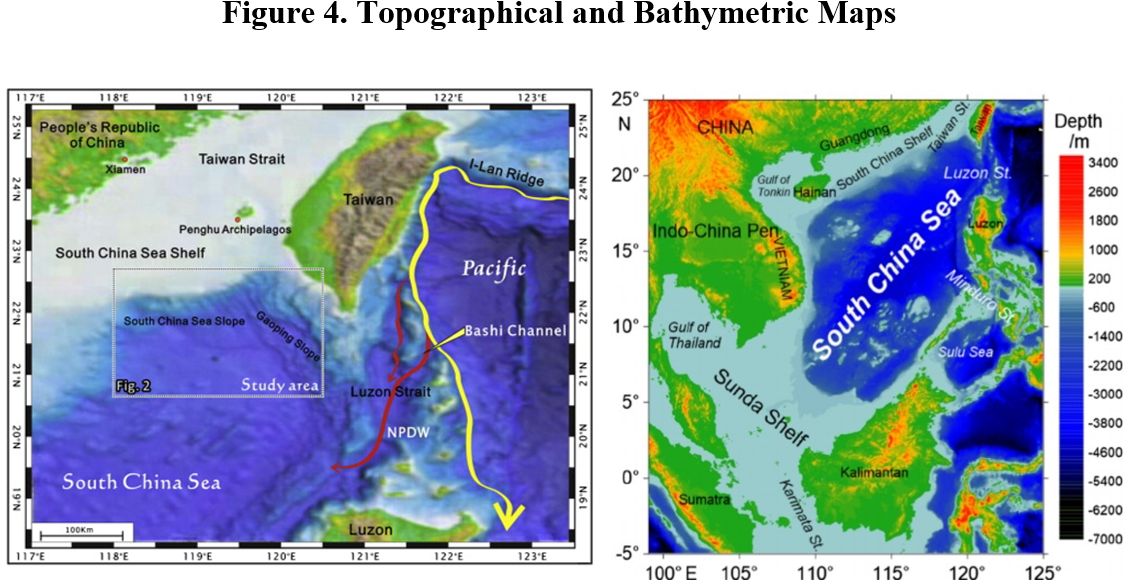

The identified area of interest is particularly significant when compared to topographical and bathymetric maps shown in Figure 4. The topographical and bathymetric conditions create two natural submarine interception points against U.S. Navy’s nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSNs) in the northern part of the South China Sea. The first opportunity is in the Bashi Channel and Luzon Strait, which have shallow waters and few natural hideouts. The second interception opportunity in entering the Taiwan Strait is the upward slope of the South China Sea Slope, an important underwater topographic future connecting the South China Sea and mainland China. Submarines are forced to ascend along the South China Sea Slope to the shallower waters of the South China Sea Shelf.

Source: Chenglin Gong (December 2014) and Gang Wang (April 2015)

In an earlier work, Lu Li-Shih wrote that this “underwater geography, with a complicated mix of seabed sediments along with its hydrological environment and geographical location, makes the area greatly suitable for ‘submarine area hunting’ for Taiwanese forces.” If the submarine geography can indeed be considered as a good “submarine hunting ground” for the Taiwanese navy, it must also be of great interest to the PLAN as well. This could well go a long way in explaining the frequent PLAN KQ-200 sorties over this particular geographic and submarine topographic area.

Moreover, the USN dispatches its own anti-submarine and maritime patrol aircraft, P-8A Poseidon, sorties frequently to the very same geographic area (see, for example, here, here and here). The fact that the U.S. P-8s – as well as other capabilities often supporting these missions, like KC-135 aerial refueling aircraft, RC-135 and EP-3 signals-intelligence collection aircraft, or even Triton high-endurance and long-range unmanned systems – frequently orbit over either the strategic Bashi Channel (see here, here, and here) or the South China Sea Slope, further demonstrates the significance of this finding. Open-source intelligence sources have also shown the occasional simultaneous presence of both Chinese and U.S. ASW aircraft circling over the same area at the same time, suggesting a mutual interest in screening each other’s submarine movements.

In addition to another critical maritime chokepoint north of Taiwan, the Miyako Strait between the Japanese islands Miyako-shima and Okinawa, another critical chokepoint, the Bashi Channel, to the south, connect the western Pacific to the South China Sea. These geographical features also serve as conduits for any U.S. forces traveling from the continental United States, Hawaii, or bases along the Second Island Chain, such as Guam, to the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait. Therefore, the two straits are of great strategic importance to China, both in the PLA’s attempt to “break out” from the First Island Chain to the western Pacific and in denying the U.S. Navy access to the area in times of conflict. Furthermore, the South China Sea Slope offers the PLA another viable interception point against U.S. SSNs entering the Taiwan Strait.

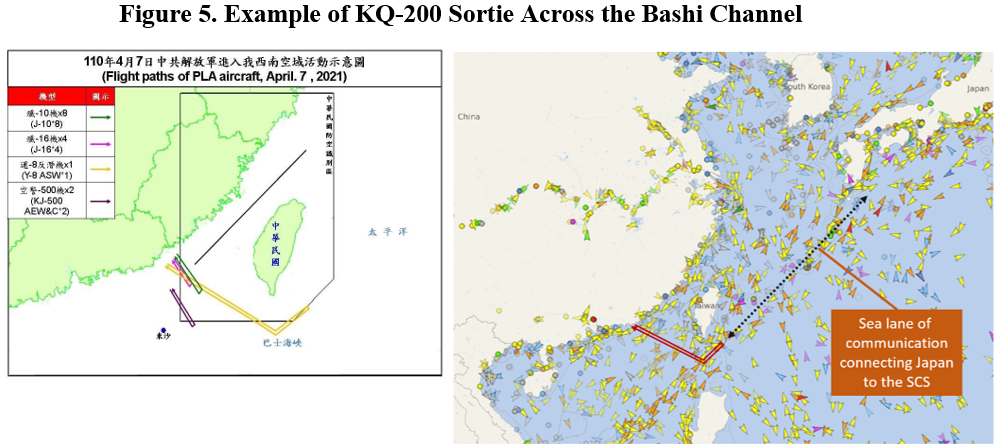

Another plausible explanation for the near daily intrusions of the KQ-200 in the area and, especially, flights across the Bashi Channel to the western Pacific, relate to the type’s function as the PLAN’s primary maritime patrol aircraft. The type is not just an anti-submarine warfare aircraft but also an effective maritime patrol aircraft. Figure 5 illustrates the type’s occasional long-distance missions, taking the aircraft across the Bashi Channel and into the western Pacific. The data provided by Taiwan’s MND also show the aircraft’s typical flightpath turning northeast along the sea lanes of communication coming from Japan’s direction toward the South China Sea. Importantly, this is also the direction from which USN vessels based in Yokosuka, Japan, would arrive in the area. Additionally, the USN and Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force often conduct joint exercises south of Okinawa, in the Philippine Sea. This is arguably all of great interest to the PLA in collecting intelligence information about USN movements.

Source: Ministry of National Defense (Taiwan) and Vessel Finder

Lastly, as I have discussed elsewhere, the heavily tasked KQ-200s are also a typical element of larger formations intruding into Taiwan’s southwest ADIZ. The type is frequently recorded as a part of a specific incursion pattern that strongly resembles maritime strike training (see here, here and here), searching for surface targets and relaying target information to the anti-shipping capable combat aircraft. Moreover, in case of large-scale incursions, involving at least 10 aircraft, at least one KQ-200 has usually been part of the formation. In some occasions, two KQ-200s have been present, leading separate elements of the larger formation (see here and here). The KQ-200 is typically recorded leading these mixed formations, which include anti-shipping-capable H-6K bombers and special mission aircraft like electronic warfare or intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance platforms, as well as escorting fighters through the Bashi Channel into the western Pacific (see Figure 5). The involvement of the KQ-200 in such formations points strongly to maritime strike training. Furthermore, in several cases these large-scale incursions have coincided with USN carrier strike group presence missions (see here, here, and here) entering or exiting the South China Sea via the Bashi Channel. Most recently, the largest incursion recorded to date, on October 4, involving 52 aircraft, was very likely a response to the simultaneous movement of two carrier strike groups – USS Carl Vinson and HMS Queen Elizbeth – through the Bashi Channel.

The conventional narrative frames Taiwan as the target of Chinese air incursions. By contrast, the median incursion type, including the most frequent intruder, the KQ-200, demonstrates clearly that these incursions have a rationale beyond Taiwan. The KQ-200 sorties, for example, most likely represent the PLA’s actual strategic and operational interests in monitoring foreign warship movements, not least U.S. aircraft carrier strike groups entering or exiting the First Island Chain through the Bashi Channel. Similarly, the PLA has a great interest in trying to find and “prosecute” U.S. SSNs entering the South China Sea or the Taiwan Strait via the Bashi Channel and the South China Sea Slope.

These findings go a long way in explaining the rationale of the near daily KQ-200 intrusions into Taiwan’s southwest ADIZ. This also serves to underline that, for reasons of geography and topography, the PLANAF KQ-200s would venture into and orbit around the very geographical areas regardless of the existence of Taiwan’s ADIZ.