The Forum on China Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), a gathering of Chinese and African officials that has been held seven times (including three leaders’ summits) since its inauguration in 2000, has always been known – and occasionally chastised – for being highly government-focused. At the same time, however, a quiet transformation has been taking place: Investors have begun to dominate China-Africa finance.

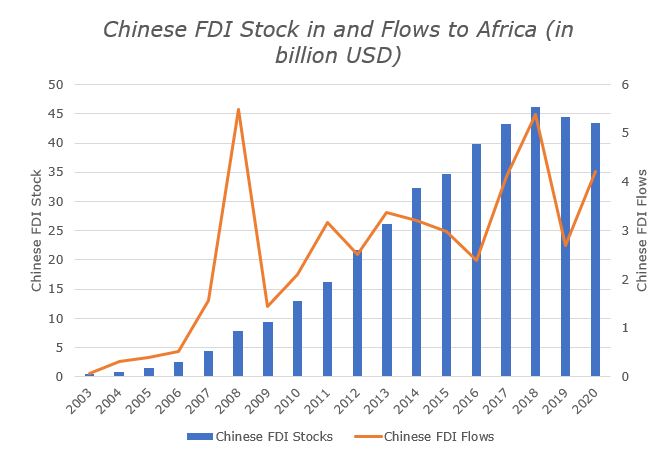

Since 2003, the earliest date official data is available, annual flows of Chinese foreign direct investment to Africa has risen significantly – from a mere $74.8 million in 2003 to $5.4 billion in 2018. Chinese FDI flows to Africa declined in 2019 to $2.7 billion, and then – despite the COVID-19 pandemic – swung up again to $4.2 billion in 2020. Over the same period, Chinese FDI stocks in Africa grew nearly 100-fold over a 17-year period – from $490 million in 2003 to $43.4 billion in 2020, peaking in 2018 at $46.1 billion. That makes China Africa’s fourth largest investor, ahead of the United States since 2014.

Loans from China to Africa – estimated at $153 billion between 2000-2019 – have dominated headlines. By comparison, investment flows attract far less attention, despite amounting to a third of the loans.

Data from the Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment.

There are two key reasons for this discrepancy, which in turn have implications for the FOCAC Summit this month.

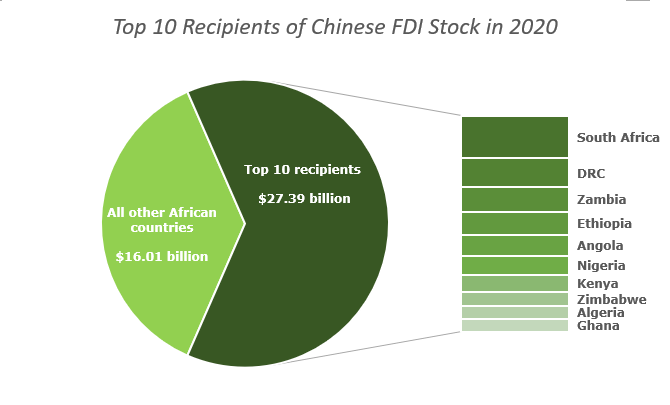

First, although almost every single African country has borrowed from China and attracted private sector investment from China over the last 20 years (even Eswatini and Sahrawi Arab Republic, which have no diplomatic relations with China, have done both), investment flows are quite concentrated, just like loans. The top 10 recipients of loans – accounting for 68 percent of the total – include varied countries such as Angola, Ethiopia, Zambia, and Cameroon. The top 10 recipients of FDI – such as the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and South Africa – accounted for 63 percent of total Chinese FDI stock in Africa.

As a result, excluding the top 10 recipients, the average amount of Chinese FDI stock in each country is approximately $380 million. This is at least half the average amount received from loans, and in FDI terms is not particularly significant – it is the equivalent of investing in one textile factory employing 2,000 people. It is not particularly “transformational,” albeit a good start.

Data from the Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment.

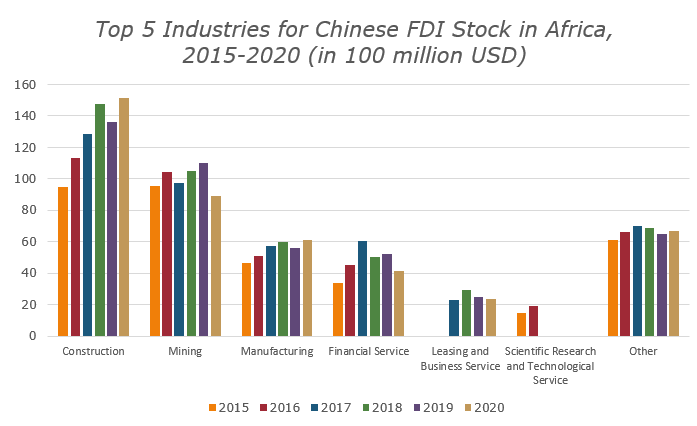

Second, the investment has been concentrated in a few key sectors. The construction sector, for example the building of Chinese-operated special economic zones or toll roads or bridges, has been the largest channel for Chinese FDI for five years, accounting for 35 percent of total investment in 2020. Next, FDI has gone into mining. While the proportion of Chinese FDI into mining (21 percent in 2020) is far lower than that of other countries such as U.K., France, and the U.S. (43 percent, 43 percent, and 37 percent in 2019 respectively), growth in other sectors such as manufacturing, tourism, or financial services – which tend to deliver more employment and broader economic spillovers – has been more limited. Lower impact equals lower noise.

Data from the Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment.

So, what does this mean for the forthcoming FOCAC, set for November 29 to 30 in Dakar, Senegal?

In 2018 the Chinese and African governments agreed on a $10 billion FDI goal over three years. If the rebound seen in 2020 continues into 2021, this target may well be met, and a further three year or more goal could be announced at FOCAC Dakar. Indeed, one of the documents expected to be agreed at Dakar is a vision for China-Africa cooperation to 2035.

What could this goal look like? Assuming a 5 percent annual growth rate from 2020 levels – as has been experienced over the last five years – Chinese FDI stocks in Africa could reach $90 billion by 2035. A 10 percent growth rate would imply stocks of $181 billion by 2035, which could quickly make China Africa’s largest foreign investor, unless the pace of investment by others picks up. This is not unrealistic. Over 2011-2015, China’s FDI to Africa grew by 21 percent annually.

But the distribution and quality of FDI will also be important to track. If China’s FDI spreads to more countries, and diversifies into other sectors, while continuing in the construction sector and even some aspects of mining (for example, processing and value addition) this could have significant impacts. For example, in the wake of COVID-19, African countries have called for investment into local pharmaceutical manufacturing, and investment into digital connectivity – both hardware and software. If Africa is to become the world’s manufacturing hub by 2063, investment in renewable energy to power both Africa’s homes and factories needs to scale up fast.

There are now over 100 operational industrial parks across the continent that could act as anchors for Chinese firms to invest into modernizing and scaling up existing factories or creating new joint ventures with African firms to create more jobs. African countries could also work with their own private sectors to develop bespoke Chinese FDI attraction or marketing plans, pitching ideas with the highest local benefits and returns. China has already published new guidelines aimed at encouraging Chinese firms to do better in terms of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) impacts.

While the actions of Chinese investors in Africa have been virtually ignored compared to loans from China’s banks, after FOCAC Dakar the former will almost certainly become more important. The question will be whether the quality and diversity of that investment can simultaneously be driven up.