As President Xi Jinping completed his speech at the eighth Ministerial Conference of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) to an African and Chinese audience in Dakar, Senegal, fingers went to work to report the 33 percent percent drop in Chinese finance, widely reported to be the key outcome from the two-day conference. While the announcement of a commitment of a $1 billion-worth of vaccine doses also hit headlines, the overall sentiment seemed to be: We knew the Africa-China relationship would begin to deteriorate! Perhaps taking advantage of this apparent sentiment, the EU published more detailed plans for a new scheme to – in the EU’s words – “mobilize” 300 billion euros of finance to poorer countries (not African countries specifically).

However, the four key documents from FOCAC were not formally published until several days later, meaning few journalists could really understand the overall direction and intentionality of the conference immediately after it closed on November 30. This iteration of FOCAC adopted the largest number of – and longest – outcome documents in a single session (usually only two are adopted). A careful read of these documents indicates an Africa-China relationship that respective governments hope will not just intensify but will also become more Africa-led. Here’s why.

Our analysis suggests that if the outcomes promised at FOCAC 8 are met, the Africa-China relationship will become very significant in four specific areas.

First, while China is already the largest supplier of vaccine doses to African countries, having sent 200 million doses to date, now China could become Africa’s largest vaccine donor, with a commitment to donate $600 million doses and locally manufacture $400 million doses with partners on the continent. This will be a big step up in itself – so far only 1 million does have been completed by Egyptian manufacturer VACSERA under a joint production agreement.

Second, while China is the largest bilateral trade partner for Africa, with a combined trade value of $187 billion, the targets of China receiving $300 billion in African imports over 2022-2024 and $300 billion in annual trade by 2035 would make China Africa’s largest export destination – surpassing the EU as a whole, which been importing around $100 billion in African goods for years. From a Chinese perspective, if these trade targets are met, the African region will become as important for trade as the Latin American and Caribbean region is now.

Third, it could move China from fourth-place investor in the continent to a top position within the next 10 years, given the targets for $10 billion in new FDI by 2024 and $60 billion in additional FDI by 2035, which we believe to be conservative in any case. According to the Chinese Ministry of Commerce, China’s FDI to Africa was $2.96 billion in 2020, a year of COVID-19 lockdowns.

Fourth, and last but not least, with the pledge to reallocate $10 billion of its Special Drawing Rights to African countries, China became the leading G-20 country in this area. Most others have pledged 20 percent or less, while some have also not specified a geographic region to receive SDRs.

What of headlines that China seems to be planning to cut loans to African countries by a third? Many pointed to that a proof that China’s banks must agree with many other analysts that African countries are in a general “debt crisis.”

Two key revelatory sentences in this year’s very long action plan are the recognition of the “persistent infrastructure gap” in Africa – a key challenge to the perennial “debt crisis narrative” – alongside the explicit promise that China will provide more concessional loans to African countries. Furthermore, as indicated above, there are other financial commitments outlined in the plan. So what to make of the absence of a monetary commitment when it comes to loans from China, or even aid from China?

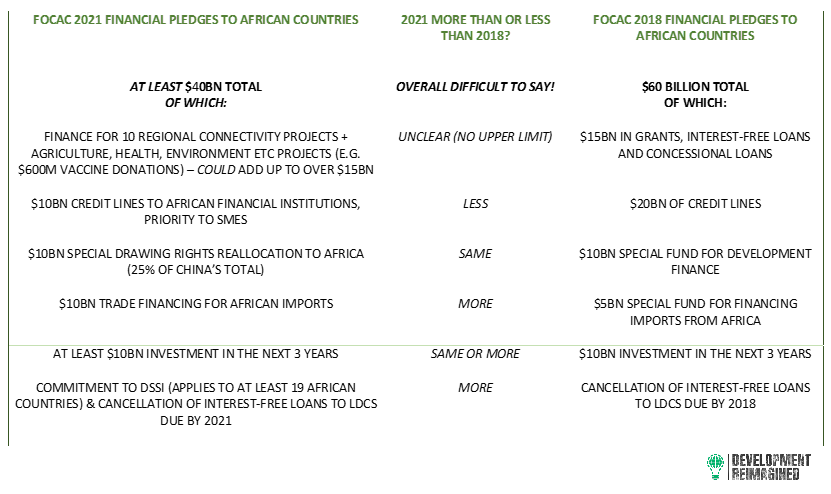

One way to think about this, as evident from our comparison table below, is that in 2018, China effectively put both a target but also an upper limit on aid and loans to African countries at $15 billion – this is the part of the overall 2018 $60 billion commitment that is now “missing” in 2021. However, looking at other commitments in the speeches and action plan – whether on regional connectivity projects or vaccine donation, which would need to be financed by aid or loans – the total value of these could easily exceed $15 billion.

Hence, unlike other analysts, we do not expect aid or loans from China to decrease in the coming years. As such, we believe African stakeholders need to work closely together now to coordinate new, high-return proposals for borrowing at low interest from China to spur economic recovery from COVID-19.

Finally, in terms of intensification of the relationship, the plan indicates a much stronger emphasis than ever on digital cooperation, and the role of the private sector. The scope for digital cooperation envisioned is wide – ranging from satellite cooperation to education, smart cities, and e-commerce for trade, much of which will undoubtably involve Chinese private sector companies. When it comes to the private sector, the emphasis is on more environmental and social responsibility, plus reorienting investment sectors away from raw minerals into manufacturing and industrialization, along with a new push on reciprocal commitments to business-friendly environments – something just as important for African companies operating in China as it is for Chinese companies operating in Africa.

The overall direction of Africa-China relations, then, is intensification rather than a cooling. Not only that, but the plans unveiled at FOCAC 8 are more African-led – again, based on, a careful reading of all of the speeches and documents in comparison to previous declarations and action plans.

With Senegal’s co-chairing of this meeting, the collective African input into these documents is more recognizable than ever. There are references to all six of the 10-year frameworks of the African Union’s Agenda 2063 – the continent’s collective development plan – an increase since 2018, which only recognized two of the frameworks. The FOCAC 8 documents also make numerous references to many of Africa’s 15 flagship projects – from transport to energy and infrastructure planning, as well as the African Union’s gender and women’s empowerment strategy. While the African Development Bank (AfDB) and Africa Center for Disease Control (Africa CDC) were both referred to in 2018, they get several mentions in 2021 alongside newer African-led institutions such as the Africa Vaccine Acquisition Task Team (AVATT), the African Medicines Agency (AMA), and the African Medicines Regulation and Harmonization (AMRH) program. This might seem like bureaucratic speak, but it can make a huge difference to African countries. In 2020, the Alibaba foundation partnered with Africa CDC to deliver equal amounts of initial COVID-19 medical equipment to 53 African countries – providing an initial buffer for everyone, rather than cherry-picking favorites or strategic partners.

Furthermore, we are also aware – through our support to African stakeholders in preparing for FOCAC 2021 – that there were key asks relating to ensuring more and better delivered financing for African SMEs, and on mechanisms to increase the volume and value of exports from African countries to China. While not all of these were successfully negotiated – most notable was the absence of a commitment to a preferential trade agreement for all African countries under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) – there are positive signals including a working group with the AfCFTA secretariat, and perhaps more excitingly the promise to launch a process to recognize African geographical indications in China – something no other development partner has ever committed to, but which could have a huge impact on the trade value of agricultural and processed goods from textiles to wine.

One key phrase is missing from the package of documents: the phrase of a “just transition,” referring to the potential to use and finance certain types of non-renewable energy on the route to green development. That said, in the climate plan, China reiterates its commitment to stop coal financing and replace this with “clean” and “renewable” energy projects, an area that has received less finance from China in the past in comparison to transport projects. So this space is worth watching, even if the future trajectory is unclear.

There is no doubt that COVID-19 has made all cooperation difficult. Africa-China cooperation has certainly suffered, with drops in trade and investment in 2020 in particular. But a reading of the conference outcomes that suggest the relationship is decreasing in importance and ambition is misleading. The proposals signal an intensification. The biggest question is whether African governments and organizations – having now left a stronger impact on the outcomes than ever before under Senegal’s co-leadership – can keep up the momentum and really make sure the commitments do affect African businesses and citizens positively, and avoid negative impacts of intensification.