Recent developments in Sino-Iranian relations have had the headlines buzzing with renewed talk of an Iran-China alliance, a Chinese “shift” toward Iran that destabilizes the region and threatens U.S. interests. China is reportedly being more active in the latest round of talks in Vienna aimed at restoring the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), often informally called the Iran nuclear deal. Meanwhile, China has increased oil imports from Iran and has offered rhetorical support for the Iranian position against the United States.

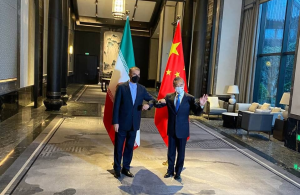

Amid these tensions, Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian visited China on January 14 to discuss the implementation of last year’s 25-Year Iran-China Strategic Cooperation Agreement. His comments, though light on specifics, emphasized a desire to develop closer ties with China in areas like trade, security, and fighting COVID-19.

Despite these events, there have simultaneously been signs that there are significant limitations to Sino-Iranian cooperation. Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi may be forced to “Look East” in the wake of the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA, but the Chinese government continues to look in many directions at once. China has substantial relations with Saudi Arabia, Israel, and a number of other Iranian neighbors and regional rivals. They are also not entirely out of step with the U.S position on Iranian nuclear weapons, and their contributions to the negotiations in Vienna reflects this. China sees Iran as just one part of a larger strategy of global engagement and economic development and is not putting all of its eggs into one basket.

Developments Since the 25-Year Iran-China Agreement

After the signing of the 25-Year Iran-China Agreement in March of last year, there were predictions of a massive influx of Chinese investment and substantial military and political cooperation. So far, these predictions have failed to come to pass. While China is buying record amounts of Iranian oil, it is not investing in production or much else. The only new deals instituted between the two governments since March have been decidedly low stakes. For example, in July, a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on museum cooperation was signed between the University of Tehran and Peking University. Another MoU on cooperation in cinema was signed between the Cinema Organization of Iran and the China Film Bureau. More recently, China opened a consulate in the southern Iranian port of Bandar Abbas, but this has yet to have any significant impact on trade.

The only significant development has been Iran’s accession to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), a Chinese-led international organization dedicated to advancing the economic, political, and cultural interests of all member states. However, the SCO is a largely toothless organization that mainly provides a platform for debate, rather than a mechanism for implementing policy. Despite its rhetoric about facilitating trade, economic, and cultural ties between members, the SCO’s track record of success in this regard has not been stellar. Iran’s membership, which will not be finalized for up to two years, was paired with the admission of Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Qatar as “dialogue partners,” a further sign that China seeks to balance Iran’s interests with concessions to its rivals.

The Rest of the Middle East

China’s relationship with other Middle Eastern countries is often glossed over in discussions of Sino-Iranian relations. The Iranian foreign minister’s visit did not happen in a vacuum, but rather in the context of a series of high-level talks the same week with Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman, Turkey, and the Gulf Cooperation Council. All of these countries already have substantial relations with China, many of which exceed the level of Sino-Iranian cooperation, and some of them – particularly Saudi Arabia – are hostile to Iran. For many of these countries, China is now their top trading partner, further emphasizing Beijing’s need to balance relations on all sides, which means not leaning too far toward Iran.

China’s relationship with Saudi Arabia exemplifies this issue. Just a few days before Amir-Abdollahian’s visit, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi met with Saudi Arabian Foreign Minister Faisal bin Farhan Al Saud in Wuxi. Wang declared that “[a]s the first foreign minister to arrive in China in the new year, your visit reflects the high-level China-Saudi Arabia comprehensive strategic partnership” and Saudi Arabia’s status as China’s “biggest trading partner and source of crude oil imports in the Middle East.” Last month, it was revealed that China has been helping Saudi Arabia to develop its own missile production program, potentially ending its reliance on purchasing foreign ballistic missiles. Although Saudi Arabia is already heavily armed by the United States, making it difficult to take U.S. claims to be concerned about an arms race seriously, the new program has the potential to significantly deter Iran from carrying out future drone strikes in Saudi Arabia.

China’s Role at Vienna

As other observers have pointed out, while China offers rhetorical support for Iran and chastises the United States for leaving the JCPOA, it is not entirely true that Beijing can be said to be on the Iranian side. China’s position is that Iran should not be subject to any form of sanctions and should have access to nuclear energy, but it is also against the proliferation of nuclear weapons and supports international oversight as a solution to the nuclear issue. While Iran desires a return to the JCPOA as well, they have made several additional demands that China has been reluctant to support, notably the demand that all sanctions be removed before negotiations. Although publicly supportive of this, behind the scenes China has reportedly been pressuring Iran to make good on promised concessions and return to the negotiating table now.

China is more a supporter of the JCPOA than the Iranian position writ large. Its support comes less out of concern for Iran’s nuclear motivations (presumably Chinese leaders understand that the Iranian government is not suicidal), but rather as a way of resolving tensions between Iran and the United States, in order to remove the sanctions against Iran. Sanctions are the main impediment to implementing the 25-Year Iran-China Agreement and improving economic ties between the two countries. Chinese investors are historically unlikely to be interested in Iran unless sanctions are lifted.

What Alliance?

Despite the recent progress made in improving Sino-Iranian relations, the partnership between the two remains limited by U.S. policy and Chinese self-interest. It was not able to prevent China from developing the military capacity of a hostile neighbor and countering a major part of Iran’s offensive strategy, and Beijing found itself in a stronger position to pressure its own ally than to pressure the United States at Vienna. There has been little to no progress on the major economic, security, and infrastructure projects projected by Western analysts and hinted at by the Iranian government.

Iran has also entered into these deals under duress, forced by extreme pressure from the United States to enter into deals that are not necessarily on terms it would like. Iranian businessmen and consumers alike complain about unfavorable terms, shoddy products, and promises broken under the threat of sanctions. In short, if the China-Iran relationship is an alliance, it is not a very good one.

Why do some continue to emphasize the threat of the Sino-Iranian alliance? From a perspective that assumes that U.S. domination of the Middle East and Asia is desirable and justified, China does pose a threat: the threat of its existence as a source of diplomatic and financial support that does not follow U.S. directives. As long as China is capable of undermining the United States’ policy of marginalizing Iran through diplomatic isolation and economic deprivation, Beijing will be seen as a threat. And of course, China has every reason to push back against the United States’ Iran strategy. Not only is the policy of “maximum pressure” in the form of sanctions that deprive ordinary Iranians of basic food and medicine morally unconscionable, but it could also easily be applied to China in a similar way.

This policy, which has failed for decades and remains fundamentally unchanged under the Biden administration, requires a justification to make up for its obvious reprehensible qualities. The threat of a China-Iran axis provides a convenient new drum for war hawks to beat, as the JCPOA has deprived them of the previous rationale: Iran’s supposed unchecked nuclear ambitions. In even the mildest interactions between Iran and China, they see a threat that “Biden cannot ignore” and which must be met with a “demonstration of force.” But the evidence does not bear out their alarmist predictions and suggests a much more limited partnership than is being portrayed.