Nearly 70 years ago, shortly after the subcontinent’s partition, a politician stood before his party and delivered an impassioned speech in praise of Urdu. It “is our language,” he said, “nurtured in our country, adding to the cultural richness of our people.”

But which country was that politician in, and who was he?

If you answered Pakistan, where Urdu has been the national language since the country’s foundation, you would be wrong. The answer is India. And if you had assumed that the speaker was Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, that is also incorrect. In fact, the man speaking was no less a giant of Indian political history than Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, the country’s first post-independence prime minister.

But despite Nehru’s advocacy for Urdu, the language’s situation in India has continued to deteriorate. In recent decades, we have seen what has amounted to a “war on Urdu.” Regardless of its recognition in the Indian Constitution and its status as the mother tongue of over 50 million Indians, Urdu has come under fire on many fronts.

Politicians have acted to restrict its use in education, place names have been changed to erase its history, and deadly riots have erupted against perceived encroachments of Urdu into public life. In 2018, two people were killed in West Bengal during protests against newly-appointed Urdu teachers. More recently, in October 2021, the use of Urdu words in an advertisement for the festival of lights, Diwali, sparked an outcry from nationalist Hindus.

As an Urdu-speaking Muslim who grew up in northern India in the 1980s, I fully understand the prejudices that speakers of the language have faced. Because of my native tongue, discrimination and hostility became features of my everyday life. I was left with the sense that I carried the burden of an unwanted legacy, a part of my city’s history that many would have been happy to erase.

Often, my Hindu classmates would taunt me, telling me to take my Urdu to Pakistan. But I did not go to Pakistan; I went to France, where I now work as the chair of the Urdu Department of a Parisian university. But even here, French people associate me first with Pakistan and cannot understand that my roots are deep in India.

Misunderstandings about how deeply Urdu is interwoven into the history and culture of India continue to abound. Urdu’s own roots are in Sanskrit, and the language developed in India, interacting with the Persian of the Mughal emperors and the Arabic of their Islamic faith. There is a very rich tradition of Urdu literature running through the history of Indian culture, and even in the final years of British rule, the independence movement used Urdu for its most popular slogan (“inquilab zinzabad” — “Long live the revolution”) and song (“Saare Jahaan se Accha”– “Better than the entire world”).

So why then has Urdu suffered such prejudice in recent times? To understand that, we need to look again at the words and actions of two towering political figures in the subcontinent’s history – the aforementioned Jinnah and Nehru – to see how political decisions that were made 75 years ago shaped the modern destiny of this ancient language.

Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Zeal for Urdu in Pakistan

Trouble began at the time of the partition of India, when the large-scale migration of Muslims to the new nation of Pakistan was accompanied by the dynamics of language shifting. Urdu was designated as Pakistan’s national language despite there being hardly any native speakers of the language there in 1947. The man who made that fateful decision was Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the driving force behind the creation of Pakistan and the country’s first governor-general.

Jinnah was, in some ways, an unlikely advocate of Urdu. A Westernized Muslim, educated in England, his mother tongue was Gujarati, and he was not well-versed in Urdu. Nevertheless, as early as 1938, he made a point of addressing crowds in Urdu, despite his general lack of fluency in the language.

Following independence, Jinnah drew inspiration from other nation states and declared Urdu as the national language of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan by insisting on its Islamic identity. In so doing, he followed the lead of the influential All India Muslim League, which had campaigned from the turn of the 20th century for Urdu to be the recognized language of all Muslims in the subcontinent.

Of course, Jinnah’s decision secured the future of Urdu in Pakistan, making the language a central component of the country’s developing identity. However, at the same time, the decision condemned Urdu in India to perceptions of an ever-closer relationship with Islam and a neighboring rival. As Pakistan turned to Urdu, the language’s prospects in India appeared bleak, until an unexpected savior emerged.

Jawaharlal Nehru’s Faithful Love of Urdu in India

In some ways, India’s first prime minister was actually a more likely advocate of Urdu than Jinnah in Pakistan. A polyglot and Cambridge graduate, he ranked Urdu among his favorite languages and even considered it as his mother tongue. Whatever happened in Pakistan did not render Urdu a foreign language for Nehru overnight. It had been born in India, and even if Pakistan tried to usurp its identity and origins, Urdu’s intrinsic value remained.

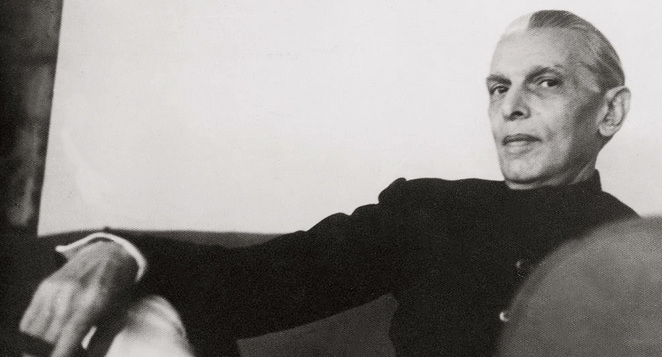

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru in 1930 (Image : Source gallica.bnf.fr / BnF)

Nehru played a major role in continuing Urdu’s legacy in India. A famous anecdote tells how when the Indian Constitution was being drawn up, a member of the drafting committee, named Satyanarayan, proposed a list of 12 languages that excluded Urdu. The general idea was that Urdu went to Pakistan.

However, not all Muslims had left for Pakistan, and Urdu was never restricted only to Muslims, being the native tongue of some Sikhs and Hindus, too. Therefore, Nehru added Urdu to the list as the 13th language. Perplexed, Satyanarayan angrily asked, “Aren’t you ashamed, you being a Brahmin, to claim Urdu as your language?”

Nehru did not respond.

Nevertheless, Nehru continued to advocate for Urdu, as the quotation at the beginning of this piece reminds us. Indeed, in a speech in Hyderabad in 1953, he chided those who criticized Urdu with words that many of the language’s modern Indian critics would do well to heed. “I have been surprised to hear voices raised against Urdu. Urdu does not compete with Hindi now. It only claims a place which is its right by inheritance in the large household of India… Why should we reject it or consider it as something foreign?”

Urdu and the Legacies of Jinnah and Nehru

Seventy-five years after partition, with the two leaders long gone, their convictions in favor of Urdu have contributed positively to the maintenance of the language. Nehru, for his part, was able to combine his love for Urdu with secular patriotism while Urdu’s identification with Islam was significant in the growth of the Pakistani nationalism that brought Jinnah to the pinnacle.

Nevertheless, that association of Urdu with Islam and with Pakistan has contributed to the language’s pariah status among many Hindu nationalists in India, creating modern tensions that are based on ignorance about Urdu’s Indian roots.

That the two founding figures of Indian and Pakistani independence were united by a shared love of Urdu speaks eloquently of the language’s rich history, which is interwoven through the culture of the subcontinent. Perhaps it is also an indication of the ties that, on a deeper level, bind India and Pakistan beneath the surface of the countries’ modern rivalries and conflicts.