“The first thing I do in the morning is sweep the dust off our tipad (terrace),” says 12-year-old Shiv Singh, a resident of Chotiya village, occupied predominantly by people of the Meena tribe in Kotputli, Rajasthan. Shiv lost his mother to Silicosis (a lung disease caused by excessive inhalation of silica dust found in mines and quarries) in 2019 and is now single-handedly taking care of his 2-year-old sibling while their father works at stone crusher across from their settlement.

“The dust from the crusher travels in the air and settles on our terrace. The air in our surroundings is so dusty that we have to tread carefully and make our way through the dense layer of dust every day. Most often we are gasping for air,” Shiv continues.

Top: 12-year-old Shiv Singh holding his 2-year-old sibling. Bottom: their dust-laden terrace at Chotiya village, Kotputli, Rajasthan. Photos by Sneha Swaminathan.

Kotputli, located between Delhi and Jaipur, is growing as an important epicenter for stone quarrying in the country. As such, several villages around the municipality continue to suffer in the shadow of illegal quarrying.

“I have not slept properly in years. The noise created by mine blasting [use of explosives to break rock for excavation] is so terrifying that I have sent my children to Jaipur, to my brother’s house,” says R. K. Meena, an entrepreneur and samaj sevi (social worker) in Shuklawas village, Kotputli. Like his fretful sleep, his house also bears the brunt of illegal mine blasting, with widening cracks in the walls.

Illegal mine blasting led to widening cracks along the length of R. K. Meena’s house in Sukhlawas village, Kotputli, Rajasthan. Photos by Sneha Swaminathan.

Apart from infrastructural damage, illegal mining is also responsible for the rise in Silicosis cases, a long-term respiratory disease occurring in people working at mines without any safety equipment. Working at the mines has also faded the fingerprints of some workers, making it difficult to use their prints to prove their identity on government documents and portals.

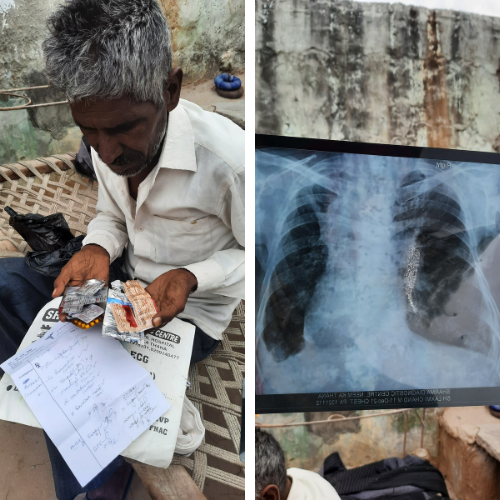

“I was diagnosed with Silicosis two years ago. Who would manage finances if I do not continue working in the mines?” says Lakhmi Chand, a 50-year-old crusher worker at Chotiya village, Kotputli.

As per the Factories Act and Employees Compensation Act, Silicosis is recognized as an occupational disease, which mandates employers pay compensation to workers who are diagnosed with it. In 2012, a Rajasthan State Human Rights Commission Scheme announced a compensation of 100,000 Indian rupees to workers diagnosed with Silicosis by government hospitals and 300,000 rupees to families of those who succumbed to it. The majority of workers are unaware of these compensations schemes, however, and even for those who do know, the process for filing for the compensation is tedious.

Left: Lakhmi Chand, a mine worker, shows his prescription and medicines for Silicosis. Right: Lakhmi Chand’s Silicosis scarred lungs. Photos by Sneha Swaminathan.

Another problematic result of illegal quarrying is crop failures in one of the driest parts of India. Most of the residential settlements in Kotputli are located in close proximity to blasting sites and crushers. The dust that is released ends up accumulating on the crops grown by the villagers.

“The yield is so poor that I have lost buyers. No matter how much we try to save the produce, the dust always overpowers us. I have now given up,” says Kamla Devi, a farmer from Chotiya Village who owns 100 square meters of land. Devi and several others filed several petitions and even protested against illegal mine blasting and environmental degradation due to excessive dust released from crushers in 2017, but nothing concrete has been done to date.

A massive portion of Kamla Devi’s crops are buried under layers of dust at Chotiya Village, Kotputli, Rajasthan. Photo by Sneha Swaminathan.

Across the municipality, the hustle to meet the growing demand for construction material and the monetary benefits from those activities has had a catastrophic impact on people, livelihoods, and the ecosystem. Activists like R. K. Meena allege that the violations by gigantic quarries and crushers go unnoticed by the authorities due to an alleged political nexus.

What remains in Kotputli is the debris of collapsed families, livelihoods, and heritage. Once an untouched Rajasthani village, Kotputli has now become a classic case of over-extraction, resource exhaustion, human rights violations, and penury.