Handling dilemmas in Myanmar is a story that goes back decades in Indian foreign policy. When Myanmar’s politically influential military, the Tatmadaw, overthrew democracy and took power three decades ago, New Delhi vociferously supported the return of democracy. But as competition with China heated up, New Delhi began to walk back that commitment.

When the Tatmadaw re-enacted a coup last year, some analysts in New Delhi argued once again that India should engage with the junta. The rationale this time around was only stronger. If geopolitical competition with China was a factor in the past, it is even more so today, given clashes between the Indian and Chinese armies in the Himalayas and rivalry over infrastructure projects.

India also appeared to have a critical security interest: Over the last couple of decades, counter-insurgency cooperation between India and Myanmar has grown. India has cooperated with the Myanmar army to hunt down and subdue separatist elements from the northeast Indian states of Assam, Manipur, and Nagaland. Many of these groups have traditionally used the thick forest cover of the border between the two countries to conduct their operations. In 2015, the Indian army conducted covert operations across the border in Myanmar against separatist insurgents from Nagaland. Four years later, India collaborated with the Tatmadaw more comprehensively to destroy sundry militant camps along the border.

Yet, in the aftermath of the coup, these equations have changed – and the choice of backing the junta is not quite as clear-cut as many realists in New Delhi would think. The current military regime is far less secure and evidently more unpopular than its predecessors years ago, with significant consequences for India’s own interests.

Protesters have stormed various cities across the country for months, refusing to back down. In September, Myanmar’s shadow opposition government, the National Unity Government, claimed that some 97 percent of the people in Mandalay and 98 percent in Yangon stopped paying for electricity, in a bid to starve the junta of funds. Some of them refused to back down even after soldiers turned up to cut power supply to their homes. For its support to the junta, even Beijing has copped significant protests and opposition within Myanmar.

Meanwhile, the junta has had few qualms about fighting back with acts that some consider to be blatantly genocidal. In the Christian-dominated Chin state, which borders India’s restive Northeast, the Tatmadaw set entire villages on fire, as it sought to extinguish a spirited resistance force based in that region. The junta’s relentless onslaught over the past several months has threatened to create a refugee crisis for India. The Chin share their ethnicity with natives in the Indian state of Mizoram, and as the Tatmadaw stormed into their villages, many of them fled across the border into India. According to one independent survey, of the approximately 20,000 refugees who sought shelter in India in 2021, as many as 18,000 were from Myanmar.

In parallel, the Tatmadaw also lost its incentive to fight for India’s cause in the Northeast. While it was previously conducting operations alongside the Indian army to root out insurgents, the junta has now begun redeploying the same insurgent groups to fight against rebel forces in Myanmar. Last November, some militants ambushed and killed six Indian security personnel in Manipur. But shortly thereafter, they escaped the pursuit of Indian security forces by fleeing back to camps across the border.

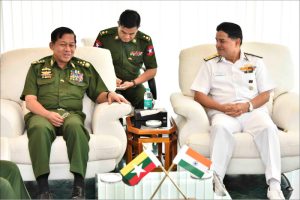

When India’s foreign secretary, Harsh Vardhan Shringla, visited Myanmar last month, he voiced some of these concerns to the ruling junta. But for as long as Myanmar remains violently unstable, New Delhi would be naïve to believe that the junta can be prevailed upon to put India’s domestic security concerns over its own Machiavellian pursuits. As things stand, regardless of New Delhi’s overtures, the ruling junta cannot address any of India’s concerns; only a return to political stability can do that.

New Delhi therefore needs to reorient its diplomatic efforts. For starters, treating the junta as a legitimate government representing Myanmar’s interests can prove to be a strategic blunder – especially when that notion is widely and popularly contested in that country and India’s past U-turns already rankle with democratic activists. India should, instead, seek to negotiate a blueprint back toward normalization with the junta, representing the interests of Myanmar’s civil society.

Toward that end, India’s biggest diplomatic asset may well be its potential ability to mediate between the West and the Tatmadaw, given deeper ties between India and the U.S. in recent years.

As it reels from a soul-crushing economic crisis, the junta is desperate to seek relief from the West. In 2020-21, Myanmar’s economy shrunk by as much as 18 percent, according to the World Bank. Economic boycotts by protesters and falling development assistance from abroad have all meant that the post-coup regime has lost about one-third the revenue of the previous government, according to one economist based in Myanmar.

New Delhi has leverage over the junta, if it is creative enough to use it. But it needs to be more proactive and realistic in its approach.