The U.S. State Department concluded in a new legal analysis that “the PRC asserts unlawful maritime claims in most of the South China Sea, including an unlawful historic rights claim.”

“With the release of this latest study, the United States calls again on the PRC to conform its maritime claims to international law as reflected in the Law of the Sea Convention, to comply with the decision of the arbitral tribunal in its award of July 12, 2016, in The South China Sea Arbitration, and to cease its unlawful and coercive activities in the South China Sea,” the department said in a press release.

The study draws heavily from the 2016 arbitral tribunal ruling, which found in the Philippines’ favor on nearly every objection Manila filed to China’s South China Sea claims and actions. China refused to participate in the arbitration and has rejected the ruling entirely, a point reiterated in its response to the State Department study. “The [arbitral tribunal] award is illegal, null and void. China does not accept or recognize it,” Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin said.

Notably, however, in the aftermath of the ruling Beijing reframed its South China Sea claims to use the jargon of UNCLOS rather than relying solely on vague claims to “historic rights,” which the tribunal had dismissed. China still continues to claim “historic rights” to the waters, but has fleshed out its maritime claims using more conventional terminology as well. While China has not defined what it means by “historic rights,” analysts believe it’s a way for Beijing to claim the remainder of the waters covered by the infamous “nine-dash line” after stretching the concepts laid out in UNCLOS to their limits. It’s worth noting that the nine-dash line claim traces its origins to the mid-1940s – 50 years before UNCLOS came into force – so naturally the nine-dash line does not reflect the legal precepts laid out in the Convention. Beijing, however, continues to use the line in official maps of its territory.

In brief, the U.S. study takes issue with four aspects of China’s claims in the South China Sea: its sovereignty claims over essentially unclaimable features; its use of straight baselines to claim waters around and between island groups; claiming maritime zones (and associated rights and entitlements) that are only accorded to archipelagic states (not island groups governed by continental states, like China); and the claims to “historic rights,” a concept not recognized in international law.

On the subject of territorial claims – the validity of China’s claim to be the rightful owner of islets in the South China Sea – the United States has historically taken a neutral position. The new document does not change that, but it does question China’s claim to “more than one hundred features in the South China Sea that are submerged below the sea surface at high tide.” UNCLOS is crystal-clear that submerged maritime features and low-tide elevations – rocks or shoals “above water at low tide but submerged at high tide” – do not generate their own territorial sea.

This was one issue of concern, for example, in the Philippines’ arbitral tribunal filing. Some of the features in question fall within the Philippines’ EEZ – if the maritime features cannot be claimed in and of themselves, the territorial sovereignty question is moot and the Philippines’ EEZ would prevail.

“[W]hile taking no position on the PRC’s sovereignty claims to particular islands in the South China Sea, the United States has rejected assertions of sovereignty based on features that do not meet the definition of an island,” the State Department concluded.

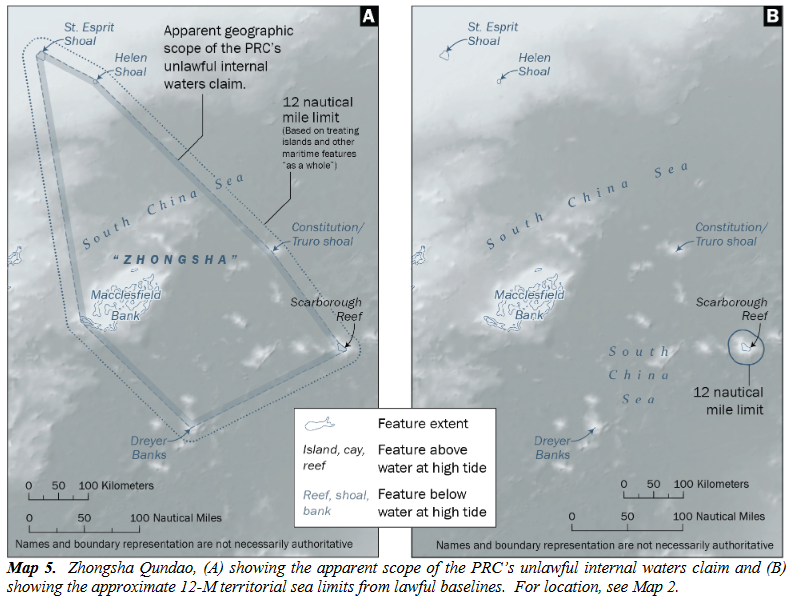

The “straight baselines” question dives deeper into maritime law, but essentially China is claiming the right to draw a circle of sovereignty around self-defined island groups (where, as noted above, many of the features in question are not islands at all, but partially or fully submerged). The graphics in the document explain the discrepancy visually.

U.S. State Department graphic from “Limits in the Seas No. 150: People’s Republic of China: Maritime Claims in the South China Sea”

On the left is China’s claim to extensive waters based on straight baselines drawn around what it calls the “Zhongsha” island group. On the right is the extent of claims permitted under UNCLOS – Macclesfield Bank, as a submerged feature, generates no entitlements, nor do the two small shoals to the northwest. And even if those were accepted as “claimable” features, drawing lines to connect them and claim the waters within, as seen in the figure on the left, would not be permitted under UNCLOS.

China’s claim to various maritime zones – internal waters, territorial seas, contiguous zones, and EEZs – hinges on a conflation of these straight baselines and its sovereignty claims over submerged or partially submerged features. If the straight baselines are invalid under international law, so is China’s claim to “internal waters” between features in the Paracel and Spratly Islands. And if no one – not China or any of the other South China Sea claimants – is entitled to claim submerged features or low-tide elevations, then these cannot be used to generate territorial seas, contiguous zones, or EEZs.

Unsurprisingly, China rejected the U.S. State Department’s analysis. “[T]he media note and study of the US side misrepresent international law to mislead the public, confuse right with wrong and upset the regional situation,” Wang, the Foreign Ministry spokesperson, declared in a regular press conference on January 13.

Pointing out that the United States itself has never signed on to UNCLOS, Wang accused the U.S. of “wantonly misrepresent[ing] the Convention and adopt[ing] double standards out of selfish gain,” while claiming China “earnestly observes the Convention in an [sic] rigid and responsible manner.”

Ironically, Wang then immediately pivoted to outlining Chinese maritime claims that are not supported by UNCLOS. He declared that China’s territories in the South China Sea have “internal waters, territorial sea, contiguous zone, Exclusive Economic Zone and continental shelf.” He did not offer any detailed explanation as to how these claims are supported by UNCLOS or address the specific arguments made in the State Department study.

Wang also repeated the claim that “China enjoys historic rights in the South China Sea.” He added: “Our sovereignty and relevant rights and interests in the South China Sea are established in the long course of history.” While Wang said these historic claims “are in line with the UN Charter, UNCLOS and other international law,” China’s consistent framing of claims rooted in historical use suggests that Beijing sees itself as entitled to non-specific additional claims on top of those provided for in UNCLOS.

Perhaps in an attempt to downplay the geopolitics of the study, the State Department release emphasized that the Limits in the Seas studies “are a longstanding legal and technical series that examine national maritime claims and boundaries and assess their consistency with international law.” The examination of China’s South China Sea claims is “the 150th in the Limits in the Seas series”; the five previous studies looked at maritime claims by Spain, Norway, Ecuador, Kiribati, and the Marshall Islands.