The past year has been a difficult one for China’s foreign policy, including still brittle relations with the United States and key allies like Australia and Britain, as well as Beijing’s diplomatic isolation exacerbated by the government’s “zero-COVID” policy. Yet that does not mean that Chinese international initiatives have completely slowed.

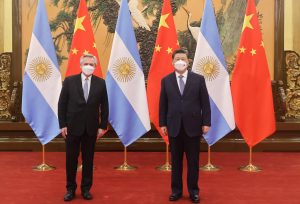

President Xi Jinping used the opening of the Beijing Winter Olympics to jumpstart meetings with numerous visiting foreign leaders. While much attention was focused on the summit between the Chinese leader and his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, another noteworthy diplomatic victory for Beijing this month was the official addition of Argentina to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), strengthening bilateral political and trade relations while also further advancing China’s interests in Latin America.

While the addition of Argentina to the BRI was made official via a memorandum of understanding (MoU) signed in Beijing by current President Alberto Fernandez, many of the foundations for the agreement were laid by previous administrations, including by Fernandez’s immediate predecessor, Mauricio Macri. The Macri government had also sought to deepen economic relations with Beijing while facing a series of domestic economic trials, underscored by ongoing debt crises (Argentina defaulted on its sovereign debts in May 2020, the ninth such occurrence since the country became independent).

Macri had attended the first Belt and Road Forum in Beijing in May 2017, signaling his country’s interests in further aligning with the initiative. This stance could be contrasted with stormy Argentine relations with the United States under the Donald Trump administration, during which time Argentina, along with Brazil, were targeted with U.S. aluminium and steel tariffs in late 2019 after the U.S. president accused both governments of currency manipulation.

When the China-U.S. trade conflict was instigated by Washington in 2018, Argentina was viewed by many Chinese policymakers as an alternative source of agricultural and food trade, including beef and soybeans, while Buenos Aires considered China a source of funding for industry and infrastructure. Chinese interests have also recently eyed investment in lithium mining in Argentina, an important development given the soaring demand for this soft metal for use in specialized batteries for electric vehicles.

Beyond trade and finance, the then-administration of Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner agreed in 2015 to permit Argentina to host a Chinese space tracking station in the southwestern province of Neuquen. These facilities have caused consternation in the United States due to their potential for strategic uses, despite the station’s civilian designation.

Tourism is another area in which the two countries have been seeking a more cooperative relationship – not only in attracting Chinese visitors to Argentina itself, but also by positioning the country as a springboard for growing numbers of tourists from China to Antarctica. Before the pandemic, there had been an emerging boom in Chinese tourism to the continent, as both polar and adventure tourism have grown in popularity.

Further investments, totalling approximately $23.7 billion, as well as a stronger banking relationship, which would build on a 2018 currency swap agreement, were promised alongside the Argentina-China BRI deal. Additional agreements addressed the potential for further bilateral collaboration in sectors including energy, technology, green initiatives, and education. A joint construction project, reportedly worth an estimated $8 billion, of the Atucha III nuclear power plant on the outskirts of Buenos Aires province was also included in the farrago of economic agreements struck during and around the Fernandez-Xi meeting.

The relationship is not all smooth sailing, however. Disputes over Chinese fishing activities near Argentina’s coast have occasionally created diplomatic tensions. In March 2016, a Chinese fishing vessel was sunk, with no casualties, by the Argentine coast guard after being caught within the country’s exclusive economic zone. Since then there have been several additional incidents of Argentine waters being breached by Chinese fishing boats, recently prompting Buenos Aires to deploy new patrol vessels to better combat the problem. But overall, from a diplomatic viewpoint, both the BRI deal and the deepened financial relationships promised between the two leaders appear to be working.

The joint statement last week between Fernandez and Xi not only affirmed their support for the MoU and Argentina’s greater participation in the Belt and Road project, but also included a confirmation that China “reiterates its support for the demands of full exercise of sovereignty over the Malvinas Islands” and a call for restarting negotiations concerning their status. The islands, administered by the United Kingdom as the Falklands but long claimed by Argentina, have been a diplomatic thorn for decades between the two countries and were the site of a brief conflict in 1982, which began when the then-military government of Argentina seized the islands, only to be repelled by British forces.

The Xi government had been less restrained of late in its views on the legal status of the Falklands/Malvinas, including being critical of the U.K.’s “colonial mindset,” but the joint statement last week was the most visible demonstration of Chinese support for Argentinian claims to the islands. Accordingly, it may mark yet another downturn in China-U.K. relations, which had previously been adversely affected by a series of diplomatic rifts. London’s joining of the AUKUS defense pact with the United States and Australia last year was viewed by Beijing as an attempt to contain Chinese power. Britain has also complained that the suppression of dissent in Hong Kong was a breach of the 1984 agreement that paved the way for the transfer of sovereignty of the city from Britain to China in 1997. In turn, that brought accusations by the Xi government of London’s neocolonialist interference. Beijing was also critical of the decision taken by Prime Minister Boris Johnson, following the lead of the United States, to refrain from sending a British governmental delegation to the Beijing Winter Olympics.

The Johnson government was quick to refute China’s remarks concerning the islands in the joint statement, including via a tweet by Home Secretary Liz Truss referring to the Falklands as “part of the British family” while calling upon Beijing to respect the islands’ sovereignty.

Despite pauses and setbacks in the development of the Belt and Road caused by the pandemic and resulting global economic uncertainty, the Argentina BRI agreement is the latest in a series of political gains Beijing has accrued in Latin America, assisted by diplomatic initiatives such as the China-CELAC forum, which has brought together Central and South American economies with Beijing since 2015. Also this month, China and Ecuador announced the launch of bilateral free trade talks, while at the beginning of 2022 the government of Nicaragua, after having cut diplomatic ties with Taipei in December last year, confirmed its interest in developing stronger Chinese economic ties via the BRI.

These developments present serious challenges to Washington as it seeks to regain political momentum in Latin America following years of diplomatic neglect under former President Donald Trump. Plans have been mooted by the Joe Biden government to expand the nascent U.S.-led Build Back Better World (B3W) project into the region. However, Argentina’s addition to the Belt and Road roster further underscores the vast amount of catching up the United States now finds itself facing.