The Falkland Islands, also known as Islas Malvinas in Spanish, a small South Atlantic archipelago off the eastern coast of Argentina, have become the focus of geopolitical scrutiny following a recent Argentina-China summit.

The Falkland/Malvinas archipelago has been officially occupied by the United Kingdom since 1833, despite Argentina’s claim to inherited sovereignty from the Spanish crown, dating back to 1767. The United Nations specifically acknowledged the territorial dispute in 1965 and set out Resolution 2065, encouraging urgent negotiations. However, tensions boiled over following several failed discussions and plans to lease back the isles, and Argentina invaded the islands in 1982, prompting a military response from the United Kingdom. The ensuing armed conflict ended 74 days later with at least 900 casualties, about 75 percent of which were Argentinians.

Post-conflict, the people living on the islands experienced greater prosperity due to increased U.K. investment and interest, as well as receiving full British citizenship and independence (except on matters concerning foreign policy and defense). A 2013 referendum saw an overwhelming majority of Falkland/Malvinas residents vote to remain a British Overseas Territory. However, Argentina’s president at the time, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, maintained that the islanders’ wishes did not factor into the territorial dispute.

Although there have been renewed demands from the region to acknowledge Argentina’s call to discuss sovereignty over the islands, the U.K. has refused to negotiate, which Argentina posits is not in “compliance with international law.”

So how exactly does China factor in?

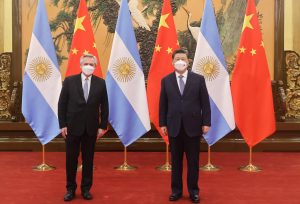

In much international press, the relationship between Argentina and China is often viewed through the lens of the Falkland/Malvinas question – in particular because on February 6 this year, the same day Argentina officially signed on to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the two countries issued a joint statement that including a reaffirmation of China’s “support for Argentina’s demand for the full exercise of sovereignty over the Malvinas Islands.” The next day, U.K. Foreign Secretary Liz Truss in a tweet affirmed the U.K.’s “complete” rejection of “any questions over the Falklands sovereignty.”

However, China’s position on the Falkland/Malvinas Islands was not new. During the two key U.N. General Assembly resolutions — Resolution 2065 in 1965 and Resolution 3160 in 1973 – China voted for Argentina’s position. Interestingly, in 1982, China, along with Poland, Spain, and the then USSR, abstained from Security Council Resolution 502 demanding that Argentina withdraw its troops from the Falkland/Malvinas – neighboring Panama was the singular vote against the motion amongst the 15 council members. The Falklands/Malvinas territorial dispute also presents a unique military interest for China concerning Taiwan, as considerable research has gone into the developments of the conflict.

Since then, for example in a joint statement in December 2018, China has made crystal clear that it supports Argentina’s claim to the Falkland/Malvinas Islands, reciprocating Argentina’s backing of the one-China policy, which claims Taiwan as part of the People’s Republic of China. And in June 2021, a Chinese diplomat said: “The question of the Malvinas Islands… is essentially a legacy of colonialism.”

This is no surprise.

However, to view Argentina-China relations only through the lens of the Falklands/Malvinas dispute misses the point. Argentina is of considerable importance. A G-20 member, it is the second largest South American economy and a major producer of soybeans and beef globally.

China has been aware of this for years. Increasing agricultural imports from Argentina helps China manage food security through diversification. Argentina is equally aware of China’s importance. In 2017 Argentina’s then President Mauricio Macri attended the first Belt and Road Forum in China.

China overtook Brazil as Argentina’s main trading partner in 2020, with total trade in 2019 valued at around $16 billion. Argentine exports to China represented 42 percent of the balance – fairly strong compared to many other developing countries, particularly because of a bilateral five-year plan for agricultural cooperation.

Argentina has also realized China’s importance when it comes to finance. Thirteen years ago, Argentina agreed to a currency swap deal with China worth just over $10 billion at the time. Argentina was not alone – 22 others including Malaysia and Indonesia also did so around the same time, and since then Nigeria and Sri Lanka have also negotiated swaps. Argentina and China renewed their swap in 2014 and 2017, and this year, in 2022, Argentina secured an increase – making the entire swap now worth $23.7 billion.

The swap entails an agreement between both countries’ central banks, where each country has a local-based account in the other’s currency, enabling the banks to draw funds from the accounts for needs and to repay with interest, including for trade settlement. For China, the swap is helpful in interacting internationally without relying too much on the dollar. For Argentina and others, the swap is similarly helpful for trade but also offers alternative options to International Monetary Fund (IMF) lending and eases foreign reserves. Argentina has experienced several fiscal crises over the years and is due to repay about $3-4 billion to the IMF in the first quarter of 2022, including interest and principal payments. So the recent increase of the China swap helps, and seems likely to continue to grow.

However, and importantly for both China and the U.K., Argentina is not just turning to China for economic support. For instance, President Alberto Fernandez has expressed openness to debt-for-climate swaps, which hold promise as Argentina is biodiverse with mixed climes and biomes and is a key target for green initiatives.

The impasse over the Falkland/Malvinas archipelago is certainly important, but while it seems to define relationships between Argentina and the U.K. it pales in significance for others. To understand or influence where both Argentina and China are going, it’s best to look well beyond the troubled archipelago.