As remembrance of U.S. President Richard Nixon’s groundbreaking trip to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) 50 years ago this week continues, it is also worthwhile to recall that Nixon’s pivot to the PRC had enormous significance beyond the United States and China. From nations neighboring China, such as Japan, to countries whose voices were – and still are – far less amplified in the major international media, Nixon’s overture to China gave cover to some and created challenges for others.

One of the strongest reactions came from India. William H. Overholt writes that Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was asked “where Indo-U.S. relations went wrong after ‘the talk all these years of an American desire to rely on India as a counterpoise in Asia to China.’ She said she supposed that U.S. policy towards India changed when ‘U.S. policy towards China changed.’”

India at the time was just 10 years removed from a border war with China, and transcripts of Nixon’s discussions in China reveal he was well aware of the consternation his trip would cause in Delhi.

In other parts of Asia, as Overholt points out, there was a sense that Nixon, the American president, had made the centuries-old mistake of seeming to be a “tribute bearer,” a supplicant seeking China’s favor. And it was not lost on many Asian governments that Nixon had asked to go to China; the Chinese had not initiated the invitation.

The U.S. outreach also reverberated in Africa, where even then China was courting African nations with aid, loans, and scholarships that didn’t come tied to the tougher terms of aid offered by Western countries.

Nixon’s trip to China gave credibility and diplomatic cover to African governments for their own close relationships with Beijing.

In May 1972, President Etienne Eyadema, then the president of Tongo, was asked by a reporter what Tongo’s reasons had been for being the only member of the Conseil de l’Entente, a West African regional cooperation forum, “which voted for the admission of Red China to the United Nations.”

Eyadema replied, “As far as we are concerned, we believe that the 800 million men of the People’s Republic of China could not be kept out of U.N. proceedings any longer. Events proved us right since the United States has now started talks with Peking and President Nixon goes as far as recognizing the existence of only one China.”

In France, had General Charles de Gaulle lived long enough, he would likely have been glad at the rapprochement, as he reportedly played a role in helping to bring it about. Reports tell of a meeting between de Gaulle and Nixon at the Elysee Palace at the end of February in 1969. Nixon is said to have “expressed to the general his desire to know the masters of China.” According to a later account, de Gaulle “immediately” ordered the French ambassador in China to tell Zhou Enlai of Nixon’s statement. De Gaulle died in 1970, but in July 1972 Nixon took the trip that solidified the China-U.S. “rapprochement which de Gaulle had been advocating for a long time.”

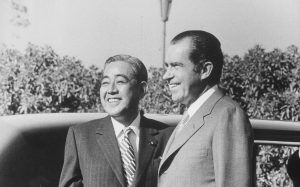

But the greatest impact – aside from the reverberations for the Republic of China government on Taiwan, of course – was felt in Japan.

The fact of the dramatic transformation of U.S. policy toward China was startling enough in and of itself. But Washington decided to provide no advance notification to the Japanese government before U.S. President Richard Nixon broadcast to the world on July 15, 1971 that National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger had just come back from China, and that Nixon himself would be going to China by May of 1972. The shock announcement caught the Japanese completely unprepared and left them feeling more than a little betrayed.

Japan believed that its post-war relationship with the United States was the cornerstone of the United States’ overall engagement with the Asia-Pacific.

The U.S. ambassador to Japan at that time, career diplomat Armin H. Meyer, later noted that Kissinger himself said that he had a made a mistake by not informing Japan in advance that U.S. policy in Asia was about to change in profound and fundamental ways. The decision was made that Japan, to be blunt, could not keep the secret.

Meyer said that Kissinger (who would remain national security advisor even after he was appointed secretary of state by Nixon in September 1973), “likes to quote from my book, where I said that I thought it over and I was very angry, but the more I thought about it, the more I felt that it couldn’t have been done much otherwise… because in those days, the Japanese were leaking everything.”

Meyer said that individuals who had facilitated the leaks were fired. But there was another reason that he found he could – reluctantly – agree with the decision to keep Japan uninformed until they heard it along with everyone else in the world.

“If you told the Japanese you’d have to tell other people including Taiwan probably, or the British, or somebody,” Meyer said. Nonetheless, and at the least, Washington “should have sent somebody about a day before to let Sato [then Japan’s prime minister] know, because Sato was discreet. You could always trust him.”

But fate intervened.

Meyer related that Washington did in fact try to inform Sato of Nixon’s impending public announcement of the United States’ seismic change of policy toward the PRC “an hour or two beforehand…They couldn’t get through and they called me and his interpreter wasn’t there and I got the Foreign Ministry interpreter to go over there and that took time and by the time they were talking, Nixon was giving his speech.”

Meyer goes on to recount how he explained the decision to Tokyo: “[W]e’ve long felt that one quarter of the world’s population cannot be ignored. [U.S. Secretary of State] Rogers had made a speech in Australia where there were sort of hints that we were trying something, and in the meantime, the Japanese themselves had been doing business over there in a big way, when we had not been doing business so, this is just a move forward.”

But, Meyer added, “the bitter thing is that we didn’t tell them.”

There have been suggestions that the trade dispute over the question of textile exports from Japan flooding the U.S. market, which so dominated the nature and tone of the relationship at that time, might have been a reason that Nixon didn’t see the need to spare Japan’s feelings by informing them in advance of what came to be known in Japan as the first Nixon Shock.

However, the ambassador said in 1996 that he hadn’t heard that theory, and that he still agreed with Kissinger’s opinion that it was simply an error not to have provided an advance briefing to Sato.

Whether it was an error, an intention, or a combination of the two, the policy move had huge implications for another Nixon political maneuver, the Nixon Doctrine.

That Doctrine, which Nixon announced in 1969, essentially said that U.S. allies facing military threats would be supported by economic and military aid rather than by the physical presence of U.S. troops on the ground. The United States would honor its treaty obligations, and would act as nuclear shield from nuclear threats, but allies would need to contribute significantly to their own defense.

The doctrine ultimately provided some cover and comfort for Japan. As the United States’ strongest ally in the Asia-Pacific, Japan then and now continues to hold a key role in security arrangements in the region. But Japan learned a lesson from the first Nixon Shock (and the second, a month later, in which Nixon took the dollar off the gold standard). Just because two countries are allies doesn’t mean that they always know one another’s plans, much less one another’s secrets.