Leading up to the March 9 presidential election, South Korea witnessed an anti-feminist backlash, a backlash that now appears to have aided in the victory of the People Power Party (PPP)’s candidate Yoon Suk-yeol.

In 2017, President Moon Jae-in campaigned on a promise of becoming a “feminist president,” promoting gender equality policies. Such efforts to alleviate gender inequity gained greater attention following South Korea’s own #MeToo movement, which emphasized women’s lived experiences, such as dealing with new age technology (including spycam or molka videos) and increasing occurrences of femicide. Yet the rise of feminist discourse quickly sparked a backlash. Conservative pundit and current chairman of the conservative PPP Lee Jun-seok described feminism under Moon’s Democratic Party as having a “totalitarian tendency.”In 2021, Lee called for the abolishment of the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, claiming that it is biased against men.

Survey research similarly shows a growing tendency, especially among younger men, to view gender equality efforts as discriminatory and equate them with preferential treatment toward women. For example, a 2019 survey by Sisain found men in their 20s were twice as likely to believe discrimination against men to be more severe than discrimination against women (68.8 percent vs. 33.6 percent).

The electoral consequences of these shifts are hard not to notice, with a January Gallup Korea poll finding a clear divergence in approval rating for Moon by gender among those in their 20s and 30s. Meanwhile, both of the main candidates, the PPP’s Yoon Suk-yeol and the Democratic Party’s Lee Jae-myung, pushed anti-feminist messages, although Lee course-corrected later on in order to woo female voters.

The anti-feminist backlash coincides with changes in the South Korean workplace. Although women are now entering the workforce at higher rates – over 70 percent of Korean women between the age of 25 and 34 work – South Korea maintains the largest gender pay gap out of all OECD countries. Workplace harassment remains a persistent problem, as existing laws often are poorly enforced. For example, 2019 South Korean laws state that businesses must “establish a workplace harassment prevention/ countermeasure system,” yet companies are not reprimanded nor fined for lack of compliance. Moreover, existing survey research suggests differences in perceptions of what constitutes harassment.

A key part of the debate is state-perpetuated gender discrimination, rooted in traditional concepts of gender roles. For instance, in January 2021 the Seoul City Government released pro-natalist, “1950s style” pregnancy guidelines, though these have since been taken down due to intense opposition. South Korea also has remarkably strict abortion laws, with the procedure only decriminalized in 2021.

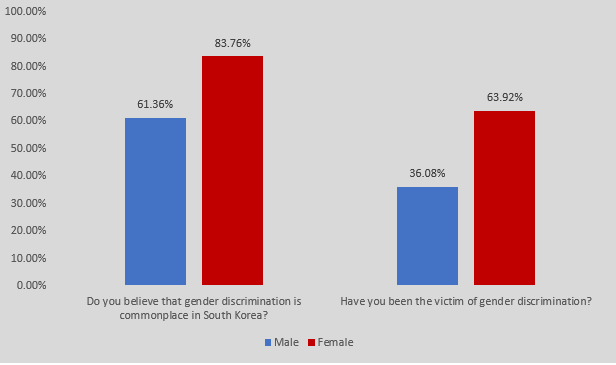

We wanted to identify how the South Korean public was viewing gender discrimination leading up to the presidential election. We surveyed 945 South Koreans during February 18-22 via Macromill Embrain and asked two interrelated questions: “Do you believe that gender discrimination is commonplace in South Korea?” and “Have you been the victim of gender discrimination?”

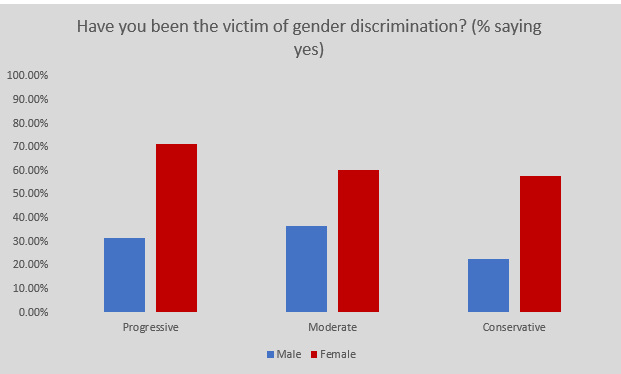

Unsurprisingly, we found females more likely to agree with both statements, with 83.76 percent seeing discrimination as commonplace compared to 61.36 percent of males, and 63.92 percent of females stating they have been a victim of discrimination compared to 36.08 percent of males. We generally see similar patterns across ideological groups (progressive, moderate, and conservative). Regressions controlling for other demographic and attitudinal factors find women were more likely to state discrimination as commonplace, while political ideology negatively corresponds with this view. Additional models find no difference among parties once controlling for ideology and other demographic factors. In terms of being a victim, regressions find that being a female, education, and income all positively correspond with stating one has been a victim, while age negatively corresponds with this.

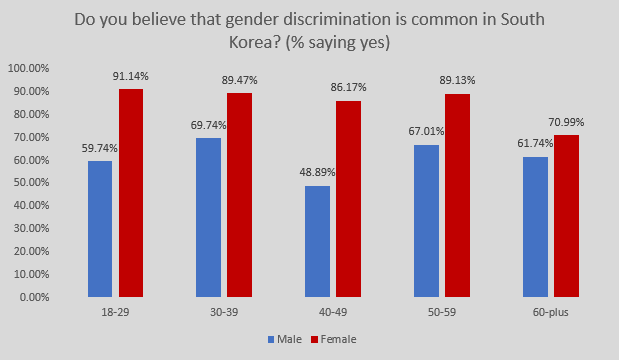

Next, we broke down responses by gender and age. We found that at least 86.5 percent of women across most age groups believe gender discrimination is commonplace, but there is not a consistent trend for men across age groups. This finding may be a result of different interpretations of what “gender discrimination” means. Women across all age categories may have broader views of what constitutes gender discrimination and are also more likely to interpret it as negatively impacting women. In contrast, men across varying age categories may be split as to whether “gender discrimination” applies to both men or women and may also have narrower definitions of it.

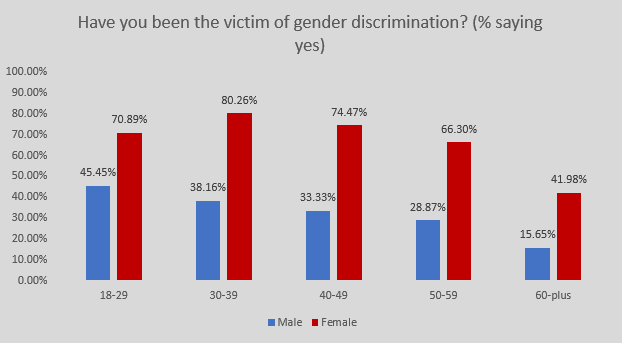

Unsurprisingly, women aged 18-29 see gender discrimination as common, more than any other gender or age group, at 91.1 percent. Women of ages 18-49 claim that they have been victims of gender discrimination at higher rates than older women, and at higher rates than men across all age categories. Consistent with previous survey work, we also found that young men, particularly those 18-29, claim that they have been victims of gender discrimination at higher rates than men in succeeding age categories. This may suggest that younger men are more likely to harbor anti-feminist sentiments as they believe that they themselves have been the victims of gender discrimination. Our survey may also be picking up young men focusing on perceived job discrimination rather than broader forms of discrimination.

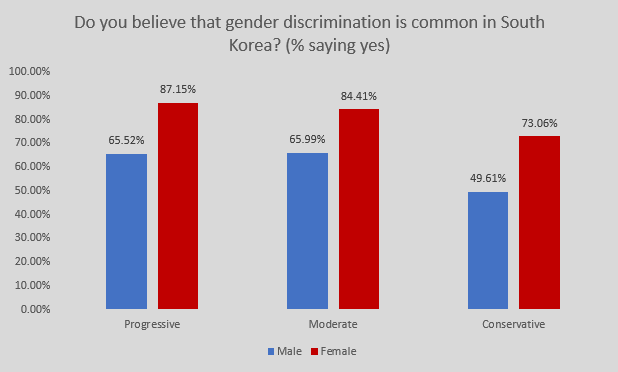

Finally, we categorized responses by gender and political ideology. There is no significant difference between the breakdown of responses across progressives and moderates. Interestingly, the largest gap between men’s and women’s perceptions of gender discrimination occurs among conservatives: just 49.6 percent of men versus 77.1 percent of women who identified as conservatives believed gender discrimination is common in South Korea. Regression analysis finds that moving from left to right on an ideology scale corresponds negatively with viewing discrimination as commonplace.

The strongest correlations, however, are associated with being a woman and having been a victim. Thus, the apparent gap between men and women who claim they have been victims of discrimination may also drive the gender gap observed in believing it is commonplace, overpowering the effect of ideological categorization. Surprisingly, our findings indicate that conservative men were less likely than their progressive and moderate counterparts to claim they have been victims of gender discrimination, suggesting that anti-feminist backlash among younger Korean men may be redefining conceptions of what constitutes discrimination.

What does this mean for President-elect Yoon? Exit polls showed a stark contrast in support among young men and women, with roughly 58 percent of men in their 20s backing Yoon compared to a similar rate of women for Lee. Meanwhile, our regression models suggest that there is no significant correlation between men who claim gender discrimination and voting for the more conservative Yoon. This may be an indirect result of both Yoon’s and Lee’s use of anti-feminist messaging during their campaigns or indicate that young men, rather than identifying explicit personal discrimination, perceived a broader environment that they viewed as discriminatory.

The increased male backlash to gender equality efforts will likely lead Yoon to attempt to follow through on his effort to abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family and continue to claim that women do not face “structural discrimination.” The result of shifting to emphasize perceived job discrimination may also have the unintended consequences of shifting attention away from broader gender discrimination and harassment in a country whose defamation laws already create an environment for legal backlash against harassment and assault claims.