Sri Lanka is currently facing its worst economic crisis since the country gained independence in 1948. In spite of constant assurances by the governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL), international rating agencies as well as economists have sounded the alarm about Sri Lanka’s ability to make its foreign debt repayments in 2022. A number of analyses indicate that Sri Lanka is on the verge of a sovereign debt default as the country’s usable foreign currency reserves plunged below $1 billion.

Day by day, warning signs about potential default are adding up. At the start of March, Sri Lanka’s Ministry of Power announced seven-and-a-half hours of daily power cuts as the country failed to purchase the oil required for electricity generation due to the foreign currency shortage. During the same week, long queues were seen at fuel stations as a result of fuel shortages. Bus owner associations even raised concerns about continuing transport services due to the fuel supply crunch.

All these events are outcomes of a severe Balance of Payment (BOP) crisis Sri Lanka has been struggling with since early 2020. With COVID-19 hitting the globe, Sri Lanka lost approximately $4 billion of annual foreign currency inflows earned from tourism. On the other hand, the adverse economic impact of COVID-19, reckless economic policy changes such as tax cuts provided in late December 2019, and the stubborn stance of the government not to seek the support of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) resulted in consistent downgrading of the country’s credit ratings. With these developments, Sri Lanka was unable to borrow from international capital markets through issuing International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs). The country has not issued a single ISB since April 2019.

Due to these developments, Sri Lanka’s foreign currency inflows reduced drastically. In 2020, the government imposed severe import restrictions, including suspending vehicle imports, to curtail foreign currency outflow. Although the forex outflow to imports was reduced, foreign debt repayment commitments remain unchanged. This means Sri Lanka’s external financing gap (the shortage of foreign currency inflows to meet foreign currency outflows) was further expanded with no option to issue ISBs. As there were no sufficient foreign currency inflows, the government continued to dry up forex reserves to pay existing loans. As a result of this foreign currency reserves declined from $7.5 billion in February 2020 to $1 billion at the end of November 2021.

The usual response to a severe BOP crisis of this nature is to seek the support of the IMF. In fact, the very reason for the establishment of the IMF was to assist countries to tackle BOP crises. Yet, the Sri Lankan government continued its stubborn refusal to seek assistance from the IMF or restructure debt.

China and India Instead of the IMF?

Since the government is adamant about not seeking IMF assistance, they looked at alternative avenues to deal with the economic crisis. Given the magnitude of the crisis, restricting imports was not sufficient to bridge the external financing gap. The island nation needed to find ways to increase foreign currency inflows.

Against this backdrop, the Sri Lankan government started to seek support from two global competing rivals: India and China. Sri Lanka has had strong economic ties with both these countries over the decades; economic relations with China in particular have gotten stronger during the last 20 years, with China emerging as the biggest bilateral lender and FDI provider to Sri Lanka. President Gotabaya Rajapaksa and many other top political leaders of the country requested economic support from both China and India to tackle the unprecedented economic crisis.

The likely reason for the Sri Lankan government opting to seek financial assistance from China and India is their unwillingness to carry out the economic reforms that are part of an IMF program. Rajapaksa’s government, immediately after its election victory, reduced tax rates and abolished several taxes. The government decided not to go ahead with the law proposed to ensure the independence of the Central Bank, a policy that is strongly advocated by the IMF. Further, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) has been controlling the exchange rate, the exact opposite of what the IMF recommends. Thus, seeking IMF assistance would mean revising most of the economic policies of the Rajapaksa government and carrying out economic reforms. Although most of these policy changes and economic reforms are the need of the hour, some of these reforms often have a high political cost. Such a policy revision would also mean an acknowledgement from the government to say: “We made a big blunder. We should not have reduced taxes.”

Sri Lanka could obtain financial assistance from China and India without such conditions. Of course, there are underlying conditions and deals in obtaining this financial assistance. But such conditions are different from the ones advocated by the IMF, as the interests of China and India are mainly geopolitical as opposed to the economic interests of the IMF.

Sri Lanka’s BOP Crisis Is Beyond Chinese Debt

In the recent past, Sri Lanka has been relying heavily on China to avoid BOP troubles. In 2018, Sri Lanka obtained a Foreign Currency Term Financing Facility (FCTFF) of $1 billion from China Development Bank (CDB). In 2017 and 2018, foreign currency inflows generated through leasing the Hambantota port to China Merchant Port Company helped Sri Lanka to boost foreign currency reserves and bridge the fiscal deficit.

After the pandemic hit the globe and Sri Lanka was unable to borrow from the international capital market, CDB extended another FCTFF of $500 million to Sri Lanka in April 2020. This was not exactly a typical export credit; this loan was directly used to strengthen Sri Lanka’s forex reserve position. According to the Finance Ministry, this was an upsizing of the previous FCTFF of $1 billion that Sri Lanka obtained from CDB in 2018.

The interest rate for the loan obtained in 2018 was the LIBOR six-month USD rate, with a 2.56 percent margin. It had a grace period of three years and a payback period of eight years. After the upsizing of the loan, for the $500 million obtained in April 2020, the interest rate was again LIBOR six-month USD and a 2.51 percent margin. It had a grace period of three years and a payback period of 10 years. So Sri Lanka was given an extra two years to pay back the $500 million loan provided in 2020 compared to the terms of the 2018 loan.

In 2021 also CDB provided two more FCTFFs to Sri Lanka, upsizing the existing loans. The first one was another $500 million loan provided in April 2021 for the same interest rate as the 2020 FCTFF, with the same grace period and payback period. Another 2 billion Chinese renminbi was provided in August 2021 with the same grace period and payback period.

However, given the magnitude of the economic crisis Sri Lanka had encountered, these loans were not sufficient to get out of serious BOP troubles and solve the severe shortage of foreign exchange reserves. During the recent visit of Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi to Sri Lanka, Rajapaksa inquired about the possibilities of restructuring the debt, considering the ongoing economic catastrophe. Despite this request, the CBSL governor continues to stress that they will meet all repayments due to international creditors.

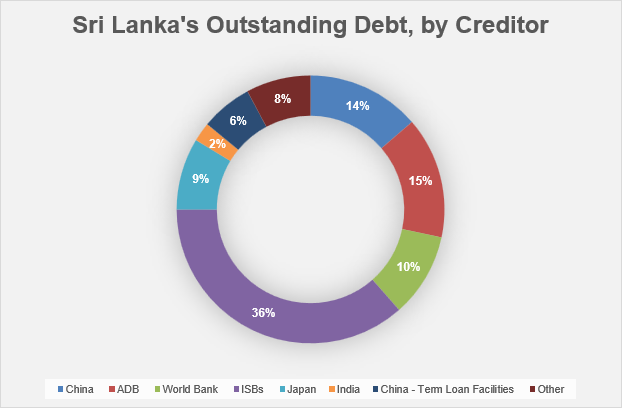

While restructuring Chinese debt would provide breathing space to Sri Lanka, it is by no means a way out of this unprecedented crisis. Contrary to the sensationalism of Sri Lanka being a victim of a Chinese “debt trap,” Sri Lanka’s debt troubles go far beyond China. The country’s economic crisis is caused by deep-rooted economic issues that have remained unaddressed for decades. Instead of addressing these issues, Sri Lanka continued to borrow from the international capital market through issuing ISBs. By the end of 2021, out of Sri Lanka’s outstanding foreign debt stock 36 percent was ISBs and only about 14 percent of the total public debt was owed to China.

The simple reality is that China cannot save Sri Lanka from a sovereign debt default by restructuring Chinese debt obtained by Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka’s debt repayments to China, including repayments of FCTFFs over the next three years, amount to approximately to 20 percent of total external debt repayments while ISB repayments amount to nearly 50 percent of the external debt repayments. Furthermore, ISB repayments include massive one-off repayments of $1 billion or more every year, posing serious threats to the country’s BOP position. As it stands now, Sri Lanka does not have sufficient foreign currency reserves to make these massive principal payments of ISBs, including a $1 billion ISB maturing in July this year, unless U.S. dollars magically appear out of thin air in Sri Lanka.

It is also evident that while China wants to keep strong economic ties with Sri Lanka, they are cautious not to take unnecessary risks. Previous currency swap arrangements attest to this.

In 2020, Sri Lanka entered into a bilateral currency swap agreement with the People’s Bank of China (PBoC). This, however, was a stand-by arrangement of 10 billion RMB ($1.5 billion) to be used for bilateral trade and other purposes over three years. Thus, it was counted as a part of the foreign currency reserves. In December, PBoC allowed Colombo to draw this 10 billion RMB to Sri Lanka’s reserves, allowing the island-nation to almost double its foreign currency reserves from $1.6 billion to 3.1 billion. According to the Chinese envoy to Sri Lanka, this swap was a unique arrangement provided by China.

However, given that the swap is in RMB, it cannot be used to make loan repayments in U.S. dollars. This swap does not help Sri Lanka to settle ISBs, which is the biggest concern pertaining to foreign loan repayments. Therefore, this currency swap is different to currency swaps provided by India in the past, which provided U.S. dollars to Sri Lanka to address issues pertaining to dollar liquidity. The currency swap with PBoC does not provide that liquidity. This means China has taken a relatively low-risk option to manage its economic ties with Sri Lanka, instead of providing a U.S. dollar loan to Sri Lanka to manage foreign currency shortages.

Reemerging Economic Ties With India

In this unprecedented economic crisis, China was not the only ally Sri Lanka sought support from. Over the last two years, Sri Lanka further strengthened economic relations with India and sought support numerous times. India too has leveraged this opportunity to expand its economic presence in Sri Lanka in light of an increasing Chinese economic presence in India’s close neighbor.

In February, as the foreign currency shortage became severe, Sri Lanka signed a $500 million credit facility with India to import fuel. This was a part of the financial package India agreed to provide to Sri Lanka to encounter the economic crisis. During the last week of February, the Sri Lankan finance minister was scheduled to visit India for the remaining part of the financial package pledged by India. Under this, Sri Lanka expected to receive a $1 billion credit facility to import essential items from India. However, the visit was postponed indefinitely due to “last minute scheduling issues.”

With these credit facilities, Sri Lanka will be able to barely manage some essential items in the short term. However, these credit facilities will not help Sri Lanka to get out of the unprecedented economic crisis. It just delays the inevitable default.

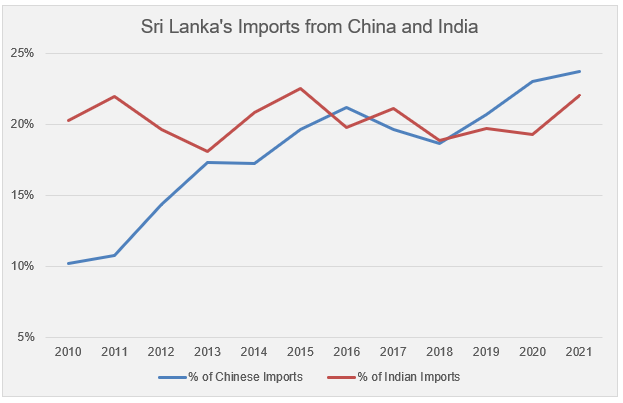

These credit facilities will likely result in India becoming the top source of imports for Sri Lanka, overtaking China. In 2018, China became the major exporter to Sri Lanka, surpassing India, which had been the top source of Sri Lanka’s imports for nearly two decades.

This economic crisis had also allowed India to fulfill its own geopolitical interests by increasing their presence in strategically important places in Sri Lanka. A subsidiary of the Indian government oil company, the Lanka Indian Oil Company (LIOC), signed a deal to develop Trincomalee oil farms as a joint venture together with Sri Lanka. Accordingly, 51 percent of the joint venture is owned by the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation while LIOC owns the remaining 49 percent. This deal had been stalled for years due to the controversial nature of the project, but the crisis presented an opportunity to India to seal the deal.

What Does the Future Hold?

As repeatedly noted in this article, Sri Lanka is on the verge of a sovereign default. Deep-rooted economic weaknesses of the country have been aggravated since the start of the pandemic. As Sri Lanka is encountering an unprecedented economic crisis, the country’s relations with China and India have also taken an interesting turn. So far, Sri Lanka has been trying to balance both countries and reap benefits from the geopolitical interests of China and India, as both countries have strategic interests in Sri Lanka. This was Sri Lanka’s strategy to avoid seeking IMF assistance and carry out economic reforms. However, this is a dangerous game to play for a country that is facing a severe economic crisis. In situations like these, vulnerable countries, Sri Lanka in this case, do not have much bargaining power; they risk compromising national interests by becoming a part of global rivalry.

On the other hand, whatever the choices made by the government – and regardless of Sri Lanka restructuring debt, defaulting on debt, or even successfully continuing to pay down its debt – Sri Lanka is going to encounter many hardships in the years to come. In such a circumstance, having the support of China and India is very crucial for Sri Lanka. Yet, Sri Lanka should be cautious about protecting its national interest when entering economic deals. The country needs to facilitate investment and trade to fix unaddressed economic issues instead of attempting to benefit from geopolitical rivalries.