While much of the world’s gaze has been fixed upon developments in Ukraine, China’s leadership has been meeting with a number of African counterparts. This has been interpreted by some to suggest that China is looking to shore up its own position on the Russia-Ukraine war. But this is a simplistic and one-sided interpretation. These meetings, organized prior to the crisis and not because of it, met African goals as much as they met China’s. In addition, evidence suggests they were not conditioned on African governments’ positions on Ukraine but rather reflected a return to the high levels of Africa-China engagement we saw before the COVID-19 pandemic.

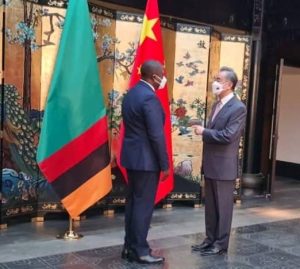

Last week, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi met with an impressive seven African counterparts. The foreign ministers of Algeria and Zambia traveled to Anhui province in China, representing the first visits by African ministers to China since 2019. Tanzania’s foreign minister had also been due to travel to China but attended the bilateral meeting virtually instead. The foreign ministers of Somalia, Egypt, The Gambia, and Niger held bilateral talks with Wang on the sidelines of the Council of Foreign Ministers summit of the Organization for Islamic Cooperation (OIC), between March 22 and 23 in Islamabad. And the week prior, Chinese President Xi Jinping spoke with South African President Cyril Ramaphosa on the phone, discussing Ukraine and the role of BRICS and G-20 countries in international affairs.

This was a significant level of engagement with African leaders, considering that Wang has also already visited three African countries (Kenya, Eritrea, and Comoros) since the beginning of 2022. Prior to COVID-19, however, this schedule of engagement would have been no surprise. African foreign minister visits to China grew from an average of four visits per year between 2014-2019 to 28 in 2019 alone, before China largely closed itself off to in-person diplomatic engagements amid the pandemic. The group of countries involved in this month’s flurry of exchanges also includes those that have historically visited China the most – for example, Tanzania.

So why now? And were these talks all about Ukraine? To understand this better, we must also look at what priorities African leaders wanted to discuss in their bilateral meetings with China.

A cursory look at the content of the bilateral discussions exposes three major themes.

The first theme is the desire for increased economic cooperation with China, following up on new commitments made at the Forum on China Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in Senegal in late 2021. For instance, Tanzanian Foreign Minister Liberata Mulamula discussed potential areas of cooperation within the context of the Tanzania Development Vision 2025, such as infrastructure for regional railways and an increase in agricultural exports to China.

Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry highlighted China’s key role in helping developing countries build climate resilience and thanked China for cooperation in this area, especially in the run up to COP 27 in Sharm El-Sheikh later this year. The importance of climate change action was echoed by Somalian Foreign Minister Abdisaid Muse Ali, who thanked China for its assistance in mitigating the effects of prolonged drought in the Horn of Africa.

Increased cooperation was a priority also for Zambian Foreign Affairs Minister Stanley Kakubo, who asserted his country’s willingness to maintain a “stable business environment” and “preferential tax policies” for Chinese companies operating in Zambia.

Another theme was practical agreements. For example, Algeria and China have recently signed an agreement to invest $7 billion in fertilizer production in the Algerian province of Tebessa, estimated to create 12,000 jobs. In Egypt last week, the China-Egypt Suez Economic and Trade Cooperation Zone agreed to build a manufacturing center for steel structures, in collaboration with the China Construction Science and Industry Corporation.

In addition, the Zambian government recently signed an MOU with Chinese company Huawei to build a digital innovation hub and to provide ICT training to instructors and 5,000 students by 2025. However, no doubt the ministers also discussed Zambia’s recent cancellation – citing “overpricing” – of a $1.2 billion contract held by China Jiangxi Corporation to connect the capital Lusaka with regions rich in copper. This could very well be part of the new government’s goal to increase the transparency and sustainability of its dealings with international creditors.

Wang also reiterated China’s intention to send emergency food aid to Somalia and other countries in the region affected by severe drought.

The third and final theme was political issues. While Ukraine of course did come up, Africans also had their own national and regional priorities to discuss. Wang Yi’s meeting with Algerian Foreign Minister Ramtane Lamamra touched upon Saharawi Arab Republic and Algeria’s recent decision to recall their envoy from Spain after the latter lent its support to Morocco’s plan to give Saharawi Arab Republic autonomy. In addition, China has recently donated military equipment to Somalia in their fight against terrorist groups, and there is no doubt that discussions with Egypt touched on China’s views on Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) project, given its impact on Nile waters.

Thus, these meetings did not happen in a vacuum, but rather within the bounds of both African and Chinese foreign policy goals. Yes, Ukraine and Russia featured in the discussions, as they should, but there was a great deal more on the table.

In particular, these seven countries all have differing views on the crisis. Egypt, The Gambia, Niger, Somalia, and Zambia voted in favor of Ukraine at the March 2 U.N. General Assembly session, while Tanzania and Algeria abstained (as did China). While understanding different points of view can be helpful to China in taking its own next steps, what this demonstrates is that the meetings were not conditional on African governments aligning or not aligning with China.

This is in stark contrast to how some other countries have handled recent international engagements – for example the U.K. recently cancelled a delegation’s visit to India due to the latter’s stance on Ukraine. Chinese engagement with the African continent has continued without such strings attached, making China both a consistent and unique development partner for African countries.

These meetings also occurred within the challenging context of China’s domestic zero COVID-19 policy – both demonstrating China’s willingness to prioritize engagement with African countries and suggesting more can be expected in future.