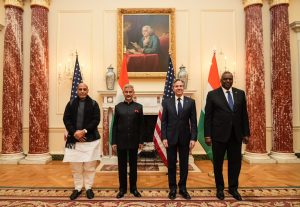

When the Indian foreign and defense ministers went to Washington last week for the high-level 2+2 talks with the United States, they were hoping to put India’s strategic partnership with the U.S. back on track. Unfortunately, the meetings — or at least the press briefings that followed — were dominated by the fracas over Ukraine and concerns over human rights abuses in India.

All told, for President Joe Biden, India has now become the center of an unlikely dilemma. When he took office last year, Biden was expected to focus on the threat from China and build a coalition of democracies against it. Early in his term, Biden hosted a Summit of Democracy toward that end. India was invited to that summit and was also positioned as a key partner in Washington’s Indo-Pacific strategy.

Then, Russia invaded Ukraine and everything changed overnight.

Last Sunday, Biden’s National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan outlined America’s three key objectives in light of this new crisis: “a free and independent Ukraine, a weakened and isolated Russia and a stronger, more unified, more determined West.”

In order to isolate Moscow, Washington has already taken several steps. A week ago, Biden signed bills that ended normal trade relations with Russia and banned Russian oil imports. Meanwhile, the U.N. General Assembly was rallied to suspend Russia from the U.N. Human Rights Council. And in tandem with European allies, the U.S. has moved to throw Russia out of the global financial system.

But if isolating Russia is now a key policy objective in Washington, India is an important obstacle. In response to these efforts, India has begun talks with Moscow to explore ways to sidestep Western sanctions, including by trading in their own currencies. Prior to the war, Russia was only a marginal energy supplier to India. But in March and April of this year alone, India has signed contracts to import more oil from Russia than it did in 2021.

Coal is in fact even more important than oil — it is the largest export commodity from Russia to India. Early this month, the European Commission proposed banning Russian coal as part of its isolation efforts. Yet, India imported more Russian coal in March than it had in any month since January 2020. India has announced that it plans to double those imports in order to bolster its steel industry.

The problem for Washington is that India has robust economic reasons to defy the West and continue such trade with Russia. And if India is indeed a U.S. ally against China, then such trade is also in Washington’s own interest, given that it would strengthen India’s hand. Cheap energy and commodities from Russia are increasingly vital for India’s post-pandemic recovery — to jumpstart an economy that was ravaged by a devastating second wave of COVID-19 infections last year. In addition, Russian arms — which still make up 60 percent of India’s artillery — are crucial in any war with China.

But Biden also has an even more fundamental question to answer: Is India really a reliable ally against China?

Much of America’s rivalry with China is now a battle of norms to shape the world: human rights, rule of law, rights of self-determination and sovereignty, freedom of navigation in the seas, a free internet, free flow of data across borders, climate action responsibility, and so on.

In recent times, many analysts have pointed out that India’s democratic backsliding puts it more at odds with Washington than with Beijing insofar as human rights issues are concerned. But even on other, relatively more technocratic issues — and in debates at the U.N., the G20 and elsewhere — India has agreed more with China than with the U.S. Last week, Washington complained that India’s proposed data localization rules would be a barrier to digital trade. India’s attitude towards those and other cyber issues are more akin to China’s than the West’s.

Critics argue that a persistent border dispute will keep India hostile to China, and thereby still give the U.S. an incentive to prop New Delhi up against Beijing. But that specter may not be as permanent as one would think. For Beijing, these serendipitous ideological commonalities are an opportunity to exploit.

As he looks set to return to office for an unprecedented third term later this year, Chinese President Xi Jinping might want to take a longer view of Chinese foreign policy. That would involve establishing China as a clear rival to the Western liberal order, building a coalition of allies for that cause, and possibly strengthening Beijing’s hand in Taiwan as it has sought to do in Hong Kong over the last few years.

In light of these challenges, troubles on the border with India — especially in the context of diminishing common ground between Washington and New Delhi — are distractive at best and destructive at worst. Last month, China conveyed to India that it seeks a broader partnership in Asia. That may become extremely alluring to Prime Minister Narendra Modi if Xi is willing to make meaningful compromises on the border.

For Biden, these shifting sands in Asia present a number of policy dilemmas that will not be easy to solve.