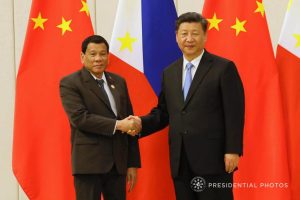

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and China’s supreme leader Xi Jinping have agreed to “broaden the space for positive engagements” in dealing with disputes over the South China Sea.

During an hour-long telephone meeting on Friday that Duterte’s office described as “open, warm, and positive,” the two leaders stressed the need to exercise restraint to maintain peace in the vital waterway, where China’s expansive claims run up against the competing (and frankly more legally defensible) claims of the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Brunei.

According to a statement from the president’s office, the two leaders also discussed the fallout from the Russia-Ukraine war and efforts to recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The leaders stressed the need to exert all efforts to maintain peace, security, and stability in the South China Sea by exercising restraint, dissipating tensions, and working on a mutually agreeable framework for functional cooperation,” the statement said. It added, “Both leaders acknowledged that even while disputes existed, both sides remained committed to broaden the space for positive engagements which reflected the dynamic and multidimensional relations of the Philippines and China.”

The statement is unlikely to amount to much. The Chinese government has made similar calls for years while doing little to stem its assertive actions in disputed regions of the South China Sea. In particular, Chinese fishing, coast guard, and maritime militia vessels have made repeated and prolonged incursions into areas claimed by the Philippines, which Beijing claims under fall within its maximalist “nine-dash line” claim. Most recently, last month, the Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) announced that Chinese vessels had maneuvered dangerously close to PCG vessels on at least four occasions over the past year near the disputed Scarborough Shoal.

Instead, the tele-summit seems set to form a bookend to the warm period of relations with China, alongside the state visit that Duterte paid to Beijing in October 2016, four months after taking office, in which he announced a sharp turn in Manila’s foreign policy toward China. “In this venue I announce my separation from the United States,” Duterte declared to his Chinese hosts, promising that he had “realigned myself in your ideological flow.”

The thinking behind Duterte’s push, to the extent that it was motivated by something besides personal animus, was that engagement with Beijing on outstanding maritime and territorial disputes would succeed where confrontation had not, while also giving the Philippines access to Chinese infrastructure funding under Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In exchange, the administration decided not to press the ruling of a Hague-based arbitral tribunal that mostly found in favor of the Philippines, in the case that was brought against China in 2013.

Since then, Duterte’s pro-China policy has pushed against the strong current of support for the U.S. alliance, both at the popular and elite levels. This has only been strengthened by the fact that the promised bonanza of large-scale infrastructure projects has failed to eventuate (though considerable amounts of Chinese cash have flowed into the Philippines.)

Given the near-unanimity of support toward the U.S., Duterte’s call with Xi marks the last high-profile engagement between the two nations before the end of Duterte’s term in June, and Manila’s likely reorientation toward the longstanding U.S. alliance. In this sense, it was telling that the Xi-Duterte discussion came on the last day of the annual Balikatan military exercises with the U.S., one of the largest in years, which involved nearly 9,000 navy, marines, air force, and army personnel, including 5,100 U.S. soldiers. Among the various scenarios, BenarNews reported, were the defense of an isolated island from foreign invaders.

Incidentally, the call also fell in the middle of a flurry of diplomatic engagements between the Philippines and Japan, which convened the first “2+2” security meeting involving defense and foreign ministers from the two countries. On April 8, Japanese Defense Minister Kishi Nobuo and Philippine Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana agreed to bolster security cooperation and expand joint military drills, amid shared concerns about China’s growing maritime clout.

This was followed the next day by a pledge by the two defense ministers, as well as Foreign Secretary Teodoro Locsin and his Japanese counterpart Hayashi Yoshimasa, to start talks on agreements on exchanging defense equipment and establishing reciprocal access, to allow Japanese and Philippine troops to visit each other’s countries for training.

It is not hard to imagine the talk between the Philippine and Chinese leaders being “open, warm, and positive,” given the apparent amity between Duterte and Xi. Based on recent history, it’s also hard to imagine this marking a significant turn in the two nations’ handling of the South China Sea disputes. Coming as it did in the final weeks of Duterte’s term in office, it seems ever likely that the sunny promises will be eclipsed as a new presidential administration reverts to the Philippine mean of warmer relations with Washington.