I know what it means when Russian President Vladimir Putin says he is “liberating” Ukraine – China’s Chairman Mao Zedong used the same slogan when he sent his troops to Tibet in 1949-50. Likewise, Putin’s allegation of rampant “neo-Nazis” in a country headed by a Jewish man echoes Mao’s accusation of “foreign powers” ruling in Tibet, a country that did everything possible to keep foreigners out in the name of protecting Buddhism. Tibetans call this “a horn on the rabbits’ head.”

But what the war in Ukraine reminds me of the most is the fundamental human determination to stand up against foreign invaders. Like the Ukrainians resisting Russian invaders, many Tibetans fought the Chinese People’s Liberation Army for years. Even after His Holiness the Dalai Lama and those who followed him escaped to northern India, the men of my hometown continued fighting the Chinese until they were captured or killed.

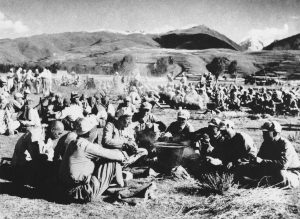

Like Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, in 1958 my grandfather and other regional chieftains as well as the monastery leaders declared “The War of 18-to-60 Fighters,” which meant all men from age 18 to 60 were to engage in the battle against the Chinese invaders. Most Tibetans had no guns but joined the fight with swords and rocks. Between September 1959 and January 1960, the CIA air-dropped arms and supplies with a few members of its trained Tibet’s Chushi Gangdruk Voluntary Army, the largest group of Tibetan fighters, on three occasions, with each delivery including several hundred rifles, light machine guns, and medicine. At least one drop not far from my town included three mortars. The weapons helped the fighters but weren’t nearly enough to equip each man.

I now think that Tibetan fighters might have saved their country if they’d had a Zelenskyy and the level of international awareness and support that Ukraine has today. Our leader, His Holiness the Dalai Lama — historically recognized as the reincarnation of the Buddha of Compassion — has long believed his singular priority is to carry out the mission of peace. He was therefore understandably against war and violence. Nevertheless, many Tibetans fought voluntarily, led by chieftains, businessmen, and monks. But in the outside world, the CIA was perhaps the only group who knew about the brutality of this war.

Many decades later a former CIA operations officer in charge of the Tibet Program, Roger McCarthy, shared long-buried news about the last battle my people fought in Chakra Palbar. “The sad, sad, sad story is that very few chose to go and leave, and understandably so,” recalled McCarthy in a video produced by Lisa Cathey, daughter of another former CIA Tibet Program officer.

“[That] group came under merciless attacks by reinforcements of Chinese who came with long range artilleries,” he said, adding that Beijing sent in an aerial bombardment. “The more accurate statement is that they killed thousands, thousands, and thousands [of Tibetans] and captured maybe a few hundred.”

Among those captured was my uncle Ngawang Rabgyal. He and many other Tibetan POWs soon died of starvation at an infamous borax mining camp in northern Tibet, where survivors estimate that tens of thousands perished.

Perhaps the success of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will be determined by Western tolerance of rising petroleum prices. But no matter what happens, as modern Tibetan history shows, people’s fight for freedom will not end even with defeat on the battlefield.

In 1969, a decade after Beijing fully controlled Tibet, people like my father and his friends re-launched their rebellion. PLA soldiers and authorities brutally killed my father, letting stray dogs carry away the limbs of his body.

Today China continues to occupy Tibet. I know why Beijing won’t label Putin’s war an invasion: Its unprovoked invasion in the 1950s also relied on a heavily distorted historical narrative designed to confuse Chinese citizens and the world. Russian soldiers’ barbaric acts, exposed through the bodies in Bucha, mirror China’s inhumane treatment of my murdered father’s body. But what they forget is that such cruelty can only make people more determined to carry their campaign from one generation to another.

When I hear reporters in Poland asking Ukrainians about how their families in Mariupol are doing, I think about how long it has been since I lost direct contact with my own family in Tibet. It’s been a decade since I was last able to speak to my siblings. I think about how China’s complete lockdown of Tibet prevents us from knowing how many Tibetans are jailed or whether any of my family members are in the now infamous re-education camps. Today, independent journalists are completely barred from entering Tibet, and if Tibetans send information about the situation that China doesn’t want the outside world to know, it could literally cost their lives.

On February 6, 2021, Kunchok Jinpa, a former schoolmate of mine, died from torture while serving a 21-year prison sentence for sending information to a friend in India about an environmental protest in Driru County in 2013. Six months before his death, a 36-year-old woman named Lhamo from Jinpa’s hometown also died from torture in prison. Her crime was sending her own money to India (and her cousin was arrested along with her for sending religious books). In 2020, a monk whose family lived near my village died from torture shortly after his release from prison. His crime was purportedly possessing the digital image of then a 3-year-old boy from India who was recognized as the reincarnation of a local lama.

In the three easternmost counties of Tibet’s Nagchu Prefecture – China’s so-called “rebellious regions,” and therefore the most restricted – Chinese authorities routinely inspect personal phones for evidence of contact with members of the Tibetan diaspora. Traces of contact are grounds for arrest and arrest can mean death by torture. In this way Tibet remains a battlefield for Chinese authorities.

Since 1987, Tibetans inside Tibet have adopted nonviolence to carry out their struggle to regain their homeland. Since 2009, at least 159 Tibetans have self-immolated, one of the recent fatalities being 25-year-old Tsewang Norbu, a popular singer from Nagchu Prefecture. Since then, at least two others have self-immolated.

The action of a 20-something pop star and 158 other self-immolators – the majority of whom are under 30 years of age – shows that resistance inside Tibet is now being carried out by the third generation of Tibetans educated under the Chinese system. In this regard, both Tibetans and Ukrainians remind us that resistance is a natural act for humans faced with their own extermination, no matter what form it might take. The act is not a choice but an affirmation of identity that becomes the bedrock of future generations.