The U.N.-designated North Korean vessel Hoe Ryong left a stretch of Chinese coastline south of Shanghai and headed back to North Korean waters in late March. That was just one of several such journeys the sanctioned ship has made in recent years, with apparently little or no effort made to hide its voyages through Chinese territorial waters.

Although the vessel’s tracking Auto Identification System (AIS) broadcasts are occasionally patchy – common practice among North Korea’s fleet of smugglers – the U.N., U.S., U.K., and EU sanctioned ship seems to be less concerned with hiding its location than many of its peers.

But the Hoe Ryong is careful in one regard: It does not visit or broadcast visits to Chinese ports. Seeing as the vessel is subject to a U.N.-mandated asset freeze, any such visit would place mandatory seizure requirements on Beijing. Being at sea just a short distance away seems to appease regulators and gives China enough wiggle room to justify its apparent lack of action.

A recently released report from the U.N. Panel of Experts (PoE) tasked with monitoring North Korean sanctions evasion notes that such North Korean ship journeys to Zhoushan, along the coast of China’s Zhejiang province, are not rare. That said, the Hoe Ryong’s U.N. blacklisted status does make the vessel stand out among most of its smuggling peers and could potentially place additional obligations on Beijing.

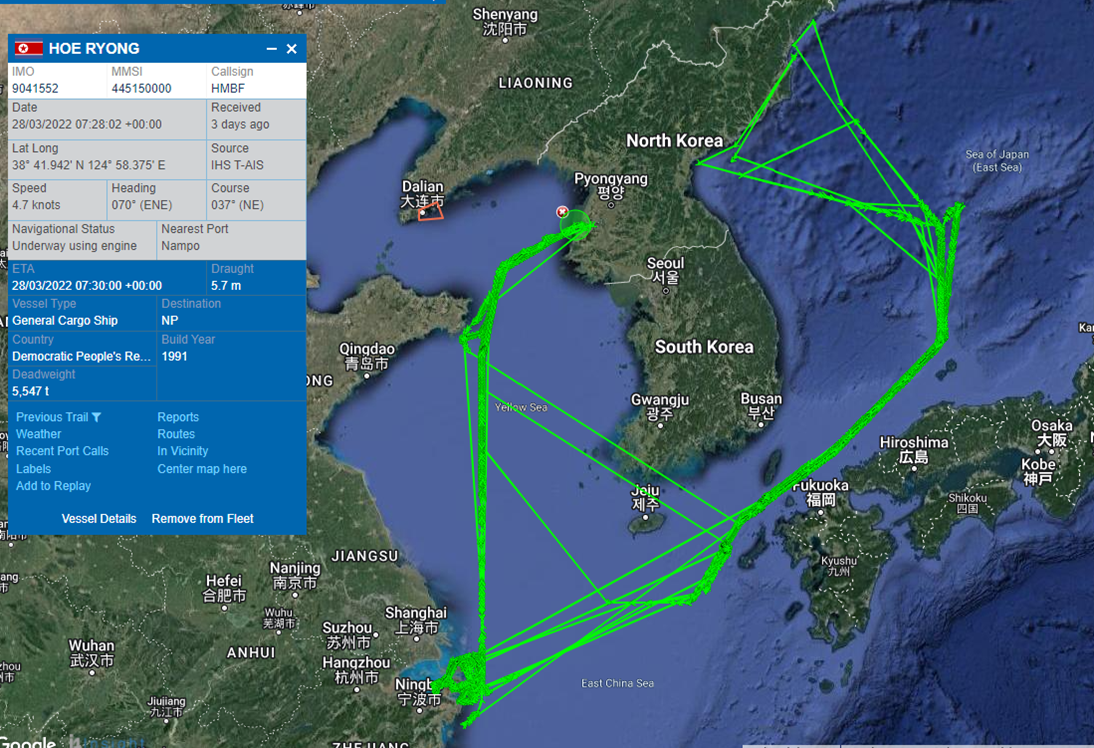

The Hoe Ryong’s recorded journeys since January 1 2020. Image: Pole Star Space Applications.

Into the Breach

The North Korea-registered Hoe Ryong has made numerous journeys around the Korean Peninsula in recent years, apparently transporting materials between North Korean coastlines via stops in waters close to Shanghai.

The Zhoushan Port Area near Shanghai is a favored hot spot for sanctions busting ship-to-ship transfers, with numerous reports noting how North Korean vessels transit to the area to exchange designated cargos like coal and oil.

Yet while most North Korean vessels take measures to conceal their movements through Chinese waters, the Hoe Ryong seems less cautious, broadcasting its location relatively consistently as it sails around the network waterways made by several large islands in the area.

Since the start of 2020, the Hoe Ryong has stopped of in the Zhoushan area five times, despite North Korea’s apparently strict COVID-19 measures, which impacted both sea- and land-borne trade.

During such visits, the sanctioned North Korean ship appears to loiter near one or more of the islands in the area for several days before setting sail once again for North Korean shores, behavior consistent with North Korean ships engaged in ship-to-ship transfers.

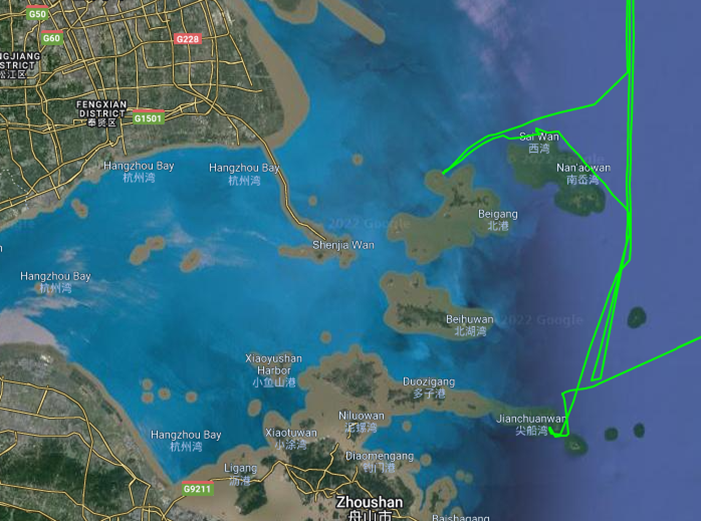

The Hoe Ryong’s route near two islands off the coast of Shanghai in 2020. Image: Pole Star Space Applications.

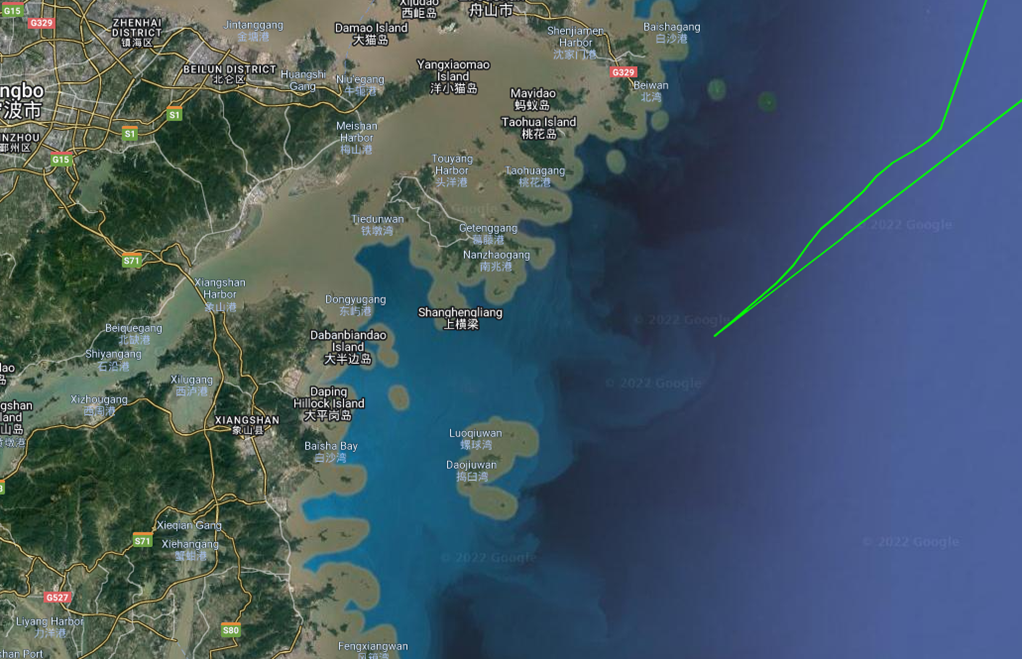

The latest such voyage coming in late March differed slightly and showed the North Korean ship apparently arriving and departing somewhere near the Chinese mainland coastline, to the south of Shanghai.

The Hoe Ryong’s route towards the Chinese mainland coastline in late March. Image: Pole Star Space Applications.

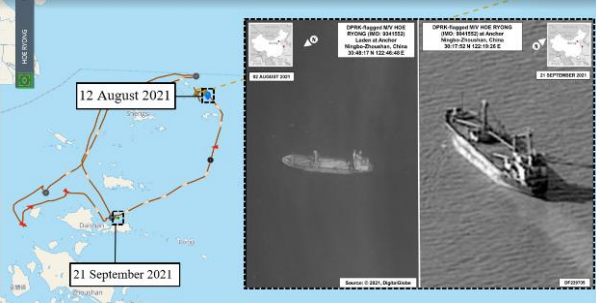

In their most recent report published on April 1, the PoE included photographs of another of the Hoe Ryong’s journeys, which took place in 2021. The PoE noted that the sanctioned ship was “riding low in water when it arrived in Ningbo-Zhoushan” but was later “observed riding high in water, indicating it had offloaded DPRK-origin coal during that period of time.”

Image: U.N. Panel of Experts.

In all visits to Chinese waters, the sanctioned ship appears to keep away from actually docking in any Chinese ports, or at least advertising any such visits. Such an action would impose interdiction requirements on Beijing. According to the U.N. Panel of Experts, when asked about the Hoe Ryong’s visit, Beijing replied “there is no record of port calls in China,” highlighting that the Chinese government believes that its U.N. obligations terminate at its shoreline.

Asset Freeze

As Pyongyang’s sanctions evasion machine has grown in scope and complexity, the wording of U.N. resolutions has become harder to parse. The U.N. Security Council (UNSC) attempted to remedy this in the last resolution passed in 2017 by clearly defining how member states should behave with regards to the “maritime interdiction of cargo vessels.”

According to 2017’s Resolution 2397, U.N. member states must interdict any vessel in a port that is carrying out sanctioned activity or transporting sanctioned cargo and “may” do so for such activity within the member state’s territorial waters.

Within the lexicon of U.N. sanctions terminology, the word “may” does a lot of heavy lifting – or no lifting at all depending on how its interpreted. It theoretically allows for member states that hold a tough stance on North Korea to investigate suspicious cargo passing through their waters, though it also allows for nations friendlier to Pyongyang to take no action and not technically breach the wording of the resolution.

Yet the story does not end there. The Hoe Ryong was listed as an asset of notorious North Korean arms dealer Ocean Maritime Management (OMM) in U.N. Resolution 2270, which clearly notes that the Hoe Ryong is subject to “asset freeze.”

The U.N.’s resolutions contain additional provisions for designated entities, with 2006’s Resolution 1718 mandating that member states freeze economic assets – like designated vessels – within their territories. Seeing as China lays claim to vast swathes of the ocean around its borders, it is not a stretch to suppose that waters immediately surrounding Chinese islands may be considered the country’s “territory.”

An additional provision in the subsequent Resolution 2397 also adds that “if a Member State has information regarding the number, name, and registry of vessels encountered in its territory or on the high seas that are designated by the Security Council … then the Member State shall notify the Committee of this information and what measures were taken to carry out an inspection, an asset freeze and impoundment or other appropriate action as authorized by the relevant provisions of resolutions.”

The key phrase in the paragraph relates to the “number, name, and registry” of the vessel, a measure likely included in the resolution as North Korean vessels tend to shuffle their identities and associated identifiers in order to evade sanctions. But notably, with designated vessels, the U.N. resolution does not consider a member state’s jurisdiction ending in its ports, using the wider terms “territory” and “high seas.”

With the Hoe Ryong broadcasting its location within Chinese waters, along with its name, IMO number, MMSI number, North Korean registration, and callsign to open sources freely available to anyone with an internet connection, it seems that a case could be made that China does indeed have such information.

Beijing may have also recently worsened its case by passing a data security law that limits foreign companies from accessing AIS ship tracking data from terrestrial Chinese receiving stations. Although some services still appear to have some access to the data, others report a 90 percent drop off.

If this data contains information on U.N. designated vessels moving through Chinese territorial waters – which it almost certainly does – then Beijing would likely be violating the wording of Resolution 2397 by not reporting such information to the U.N. and what action it took concerning it.

While the Chinese government and the U.N. Security Council have no obligation to make their communications public, the U.N. Panel of Experts’ reports do provide a window into how China typically answers U.N. investigators when pressed about clear sanctions violations in its waters, with replies usually truculent or inconclusive. To date, there has been no published information on any Chinese interdictions of suspected North Korean smuggling activity within its waters.

The microcosm of North Korean sanctions enforcement seems especially relevant in recent months with numerous countries joining forces in sanctioning Russia over its invasion of Ukraine. How China chooses to interpret the wording of U.N. resolutions in order minimize its enforcement obligations should serve as a reminder of the potential limits of sanctions policy, highlighting that countries friendly to those designated are often able to find a way to circumvent them, if the political will is present to do so.