As Shanghai enters its seventh week of COVID-19 lockdowns, China’s censors have been hard at work trying to contain an eruption of public outrage and enforce the leadership’s prohibition of any public debate or calls to reconsider its strategy.

Spikes in censorship and social media activism occur periodically in China, particularly in moments of crisis. As in past periods of extreme regime sensitivity, there are ample examples from recent weeks of censorship “overkill,” including restrictions on a WeChat account belonging to the National People’s Congress, seemingly innocuous phrases like “happy birthday,” a hashtag with the first line of China’s national anthem, and references to the Hollywood film “La La Land.”

Nevertheless, two aspects of the current campaign stand out: the high profile of some of the users being silenced and the amount of critical content that has survived online despite furious censorship efforts.

Prominent Voices Silenced

The extended lockdowns in Shanghai and additional restrictions in other cities have prompted more citizens to raise objections to the human and economic costs of the government’s “zero COVID-19” policy, with some calling on their leaders to consider less rigid alternatives that might still spare many lives. The prominence, diversity, and number of people who have encountered censorship for trying to engage in such a rational discussion are significant.

Medical professionals remain a key target for censors, as they have been since the inception of the pandemic. Indeed, the suppression of health experts’ speech in late 2019 and early 2020 may have denied the country and the world an opportunity to control the virus. Yet the practice continues.

In early April, Zhong Nanshan, the country’s top respiratory disease specialist, published an English article in the National Science Review that offered suggestions on how China could reopen “in an orderly and effective manner” in the coming months. While it acknowledged the effectiveness of policies to date, the article warned that the strict “zero COVID-19” approach “cannot be pursued in the long-run.” A Chinese version was quickly censored, and during the night of April 20–21, state media flooded Baidu search engine results with items that partially quoted Zhong expressing support for the existing strategy and downplayed his remarks on the need to gradually open up.

More grassroots health workers have also been silenced. In early April, Dr. Miu Xiaohui, a retired infectious disease expert, attempted to calculate how many people with diabetes might have died because of the lack of medicine and treatment during Shanghai’s lockdown, reaching an estimated figure of 2,141. The blog post outlining his calculation and suggestions for managing the pandemic – through a stronger focus on vaccination campaigns and home isolation, for example – was deleted.

Beyond the medical profession, financial analysts have been swept up in the attempt to stifle debate. Hao Hong, a Hong Kong–based market strategist, was censored after he published a series of commentaries on social media platforms that predicted a gloomy trajectory for China’s economy. On April 30, his Weibo account, which had 3 million followers, was shuttered, and his WeChat account was suspended. Within days, he left his position at a major financial firm, citing “personal reasons.” The Weibo accounts of at least three other chief economists and fund managers have recently been suspended for “violating laws and regulations.” The apparent purge fits a long-standing pattern in which warnings of problems for the Chinese economy are smothered despite growing evidence of a downturn.

Prominent influencers and celebrities have attracted censorship and other pressure for echoing the sentiments of many ordinary Shanghai residents. Wang Sicong, son of billionaire Wang Jianlin, had his Weibo account – with 40 million followers – shut down in late April after he posted comments questioning state-sanctioned Chinese herbal medicine treatments and declaring that he would refuse to take a mandated test. There were unverified reports that he had also been detained for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” a criminal charge often used to punish free speech. Meanwhile, rapper Fang Lue (who performs as Astro) removed a YouTube video of his song “New Slave,” which was released at the end of March and gained popularity for presciently articulating the frustration and anguish of many in Shanghai.

Censors appear to have doubled down after a May 5 meeting of the Politburo Standing Committee, during which President Xi Jinping affirmed the “zero COVID-19” policy and made clear that he would tolerate no calls for reconsideration or adjustment. The readout notes from the meeting state that the party must “resolutely struggle against all distortions, doubts, and denials of our epidemic prevention policy.”

Soon afterward, Tong Zhiwei, a law professor in Shanghai, published an online essay arguing that authorities were acting illegally when they took extreme measures such as forcing uninfected neighbors of infected individuals into collective quarantine. His verified Weibo account was then banned from posting, and a hashtag of his name was censored.

On May 10, World Health Organization (WHO) director Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus remarked that China’s strategy was “not sustainable” in the face of the virus’s easily transmissible Omicron variant. Almost immediately, as clips and references to the comment circulated online, censors descended on his remarks, suppressing his image, name, related hashtags, and even U.N.-affiliated accounts on Weibo and WeChat.

Internet Users Push Back

During the Shanghai lockdown in particular, ordinary Chinese users have gone to extraordinary lengths to circumvent censorship, keep critical content online, and find avenues for freer expression.

Creative solutions have included piggybacking on officially sanctioned hashtags. On the evening of April 13, tens of thousands of angry comments were posted to a hashtag criticizing human rights in the United States, which was artificially ranked second by the Weibo platform. Users exploited the hashtag to highlight the lack of rights protections in China and express frustration with the Chinese government. Many of the posts garnered hundreds of likes and shares, but by 4 a.m. the censors had moved in to delete them. Podcasts have also emerged as a less censored space where women in particular have shared their daily hardships during the lockdown.

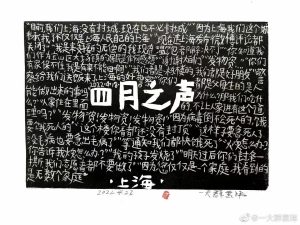

Another collective outpouring of anguish came in the form of a six-minute video compilation of key incidents from the Shanghai lockdown, titled “Voices of April.” The video deluged WeChat groups and was constantly reposted and forwarded even as censors tried to remove it. People made new versions of it upside down, embedded in cartoons, or with painted still images designed to evade censorship algorithms.

Various initiatives have countered censorship within the Chinese internet by keeping deleted content alive outside the Great Firewall. A compilation of 200 cases of people who died as a result of the lockdown itself rather than COVID-19 – from denial of medical care, hunger, or suicide, for example – was posted to Airtable, a blockchain-based database platform. Overseas bilingual websites like China Digital Times (CDT) or What’s on Weibo, along with the Twitter accounts of individual journalists and researchers, have captured, archived, and translated posts like many of those cited above. CDT also published a leaked censorship directive calling for a “comprehensive clean-up of video, screenshots, and other content related to ‘Voices of April.’”

Long-term Implications

The lockdowns, censorship, and citizen responses are likely to have long-term effects, regardless of how the pandemic and government health policies evolve.

It is noteworthy, for instance, that some of the most popular content has involved local officials – from medical facilities or residential committees – candidly expressing their own sympathy and sense of helplessness to complaining residents, indicating a degree of disillusionment and dissent among those asked to implement the government’s rigid and often brutal policies. There may be foot-dragging among censors themselves, as suggested by some of the gaps or delays in enforcement surrounding the U.S. human rights hashtag or a blog post titled “Shanghainese endurance has reached the extreme point” that garnered 20 million views before being deleted.

Reflections published by observers and Shanghai residents also underscore a disappointment with Chinese state media’s obvious lack of coverage, as well as a sense of solidarity and community surrounding both offline mutual-assistance efforts and online outbursts of collective anger. As one social media user commented in response to the U.S. human rights hashtag hijacking: “So many posts to like. This is the true voice of the people. Let’s commemorate tonight.… Maybe tomorrow it’s gonna be songs and dances again, but at least we know that we are awake.”

Digital habits may be changing under lockdown. Some users have reportedly drifted away from Chinese e-commerce platforms and even WeChat, fed up with wait times and rampant censorship, and moved toward real-life neighborliness or international apps like Telegram.

As Shanghai and other parts of China emerge from health restrictions, more information may surface regarding the costs of the government’s policy and its autocratic refusal to admit error, accept independent advice, or adjust to changing conditions. Even harsher censorship may still be coming, but it seems clear that this historic and tragic episode in the lives of millions of people will not be easily forgotten, even if much of the digital evidence is hastily obscured.