This is the third entry in John D. Van Fleet’s Shanghai Lockdown Diary in The Diplomat. Read the first two here and here.

Xujiahui, Shanghai, May 23: “Reports of our release have been greatly exaggerated.” So quipped one of the WeChat tribe here, with a hat-tip to U.S. author Mark Twain. Another complained, “What annoys me is people messaging from overseas saying, ‘I hear you’ve opened up.’”

For weeks now, we’ve heard succeeding statements about release dates, but release itself has become like a rainbow, receding into the distance as we approach it. Media coverage of the official pronouncements circle the globe; reports of the neighborhood reality, not so much.

So we live on, in limbo land.

In Shanghai, release from lockdown is not colored in black or white – it’s shades of grey. The next lighter shade for each neighborhood looks like this:

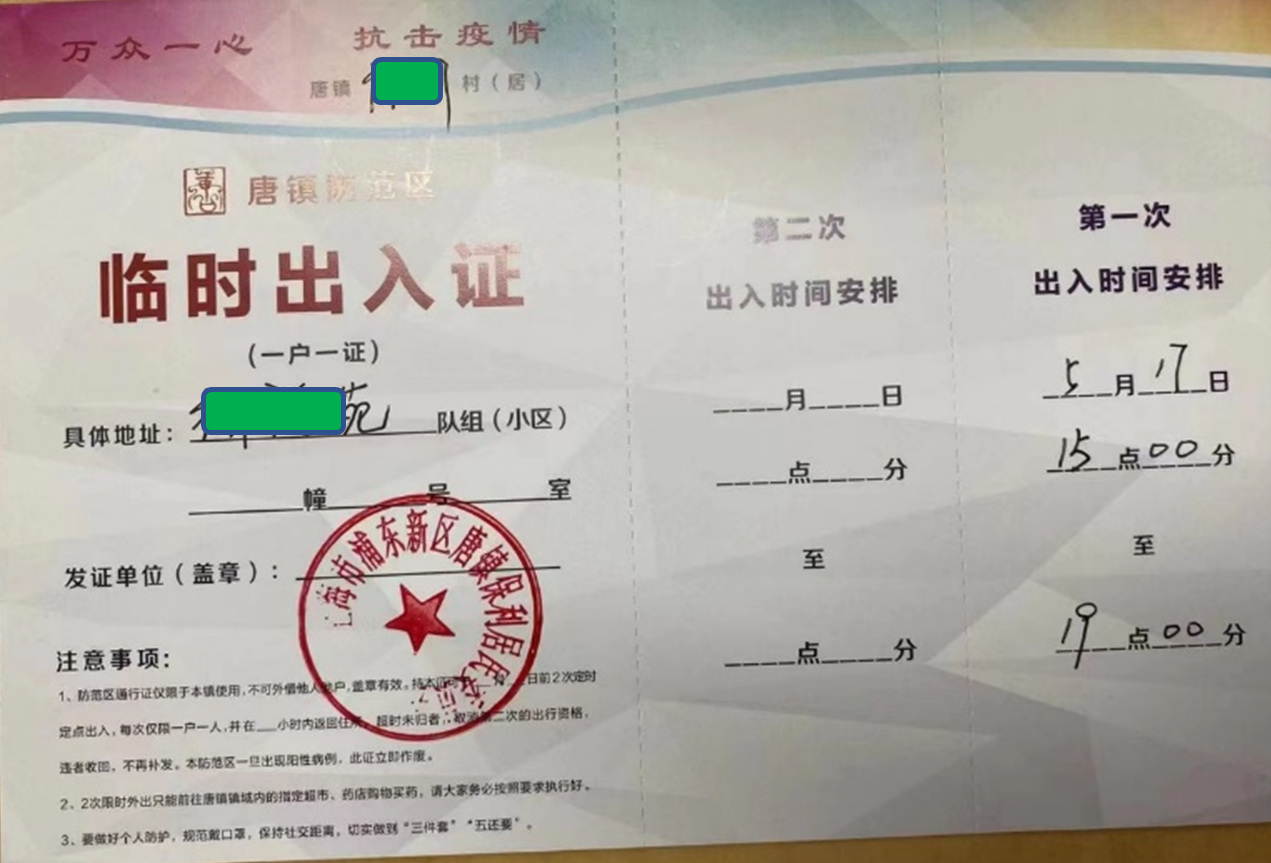

The large red characters read “temporary exit/entry certificate.” Photo from L. Liu

These temporary passes are good for only one resident per household, and only during permitted hours – this one is valid from 15:00 to 19:00, valid for two escapes over a week-long period.

Shanghai has 15 districts, each with up to dozens of subdistricts, each of those with populations ranging from thousands to hundreds of thousands. Each subdistrict will have its own printed version of the pass – the one above is for the Tangzhen subdistrict in Pudong district. Shanghai averages about 2.5 people per household, so the city will have printed about 40,000 of those for that subdistrict’s 100,000 residents. If every household in Shanghai is to receive one, about 10 million will be required, with hundreds of variations. Printers must be ecstatic.

There’s no telling how many subdistricts have issued these passes so far. Anecdotal evidence suggests maybe 25 percent. No small number of people have been able to escape, shall we say, informally as well, through side doors of compounds, openings in barriers, or similar. These escapees joyfully post images of their excursions on social media, making the rest of us jealous.

Subsequent passes may or may not be issued, depending on the situation. The district or subdistrict level will decide that too. Citywide pronouncements notwithstanding, the district and subdistrict officials know they’ll be held responsible for any breakout – of people or infections – so they quite reasonably err on the side of caution.

For the minority who, freshly printed passes in hand, have ventured out, the type of Shanghai they encounter varies widely. Some neighborhoods appear almost normal, but no one reports more than a few select shops open, with time and purchase limits on customers, also controlled by passes. Barriers divide subdistricts, bridges are blocked, and street traffic is a small fraction of usual.

Barriers between city subdistricts. Photo from R. Ballal

The city has announced (in Chinese) a plan “to gradually resume cross-district public transport” from May 22, aiming to have at least some busses and subway trains running again. That’s the next lighter shade of grey on the release spectrum.

Residents must provide proof of a negative nucleic acid test, within the past 48 hours, to use any public facilities, such as the transit system, shopping malls, and banks. How to provide such tests, readily and frequently, for nearly 30 million residents? Thousands of kiosks across the city, like the ones below, are part of the answer.

Left: Photo from Shanghai social media. Right: Photo by T. Maynard.

In the photo on the left, the large blue characters at the top read, “Convenience Station for Nucleic Acid Testing,” while the smaller ones just underneath in red read, “Always Follow Along with the Party, Building the China Dream Together.”

The government announced that they’ve already put 5,000 kiosks in place, on the way to a targeted 9,000, with the goal of having no Shanghai resident more than 15 minutes’ walk away from one. Our compound’s will be placed in an adjacent parking lot this week.

What Does Lighter Grey Look Like?

The cities that suffered from the first COVID-19 wave two years ago, like Wuhan or, say, Milan, don’t have much to teach Shanghai residents about what our future will resemble. In those days, we had no tests or vaccine, but despite the mystery and lethality of the first COVID-19 variant, most cities with restrictions didn’t face nearly Shanghai’s constraints on, for example, buying food. Stores remained open, people were allowed out to shop in them, delivery services still functioned.

The example of Xi’an, however, is relevant. From December last year, China’s Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 CE) capital locked down its residents for several weeks, in a manner similar to what we’re experiencing in Shanghai now. One Xi’an resident said, “Before the lockdown, we hardly knew our neighbors in this building. But we quickly formed a WeChat group after the lockdown started.” That matches the experience of millions in Shanghai. I earlier mentioned the remarkable, spontaneous, organic uprising of neighborhood spirit and unity that Shanghai’s lockdown has prompted.

It seems intuitive that a community of neighbors, formed organically to withstand and overcome a crisis, would maintain their cohesion and continue to work together. The Xi’an resident goes on to say, “We’re still using the WeChat group. It’s become a main channel for us to communicate with each other, to discuss how to make our community a better place.”

A few weeks ago, Shanghai sociologist Sun Zhe referred to these as “communities of common destiny.” He expects them to last here, as the Xi’an resident has seen there. Others are less convinced – they suspect that we’ll revert to the mean.

We will need our stronger communities, because our common destiny seems to include frequent testing and restrictions, and for more than just a few weeks. Chinese media use changtaihua – “normalized” – to refer to those thousands of kiosks around the city, with the implication that such testing will be with us for a while. English-language media commonly translate the term as “permanent.”

A May 19 article in Shanghai’s The Paper (in Chinese) says, “According to the most recent research published by Soochow Securities, if all first- and second-tier cities in China implement normalized nucleic acid testing in the future, the annual expenditure on nucleic acid testing nationwide will reach RMB1.45 trillion.” That’s about $225 billion. The article also suggests something that should surprise no one – companies manufacturing testing kiosks and consumables are attracting plenty of attention, and money, on Shanghai’s A-share stock market.

Thus far, China’s centuries-old regional rivalries, in particular the quintessential Beijing-Shanghai variant, have colored perceptions of Shanghai’s lockdown. On social media, provincial and northern disdain for more southerly Shanghai’s plight is easy to detect. But outbreaks all around the country will likely render those prejudices moot in time. Omicron is an equal-opportunity virus – it has no geographical preference. About 40 cities around China have endured some form of lockdown in the past few months, with the northeastern city of Changchun suffering longer than Shanghai has.

And Beijing, with a thousand plus positive test results in the past month, has entered what longtime resident and veteran journalist Melinda Liu cites as a “slow-motion lockdown.” Thousands of residents of a compound in the southeast of the city doubtless wish it had been a bit slower – despite negative test results, they were abruptly hauled off to quarantine on May 20.

Limbo Land

A May 14 headline in The Economist blares, “Shanghai’s Covid-19 lockdown is not even close to over.” “Lockdown,” the inverse of release, is also not binary. For some shades of lockdown grey, the Economist is surely right.

In Dante’s “Inferno,” the souls in Limbo yearn for salvation indefinitely, but they subsist comfortably enough. Many of us in Shanghai have suffered no real privation during these past two months – we’ve lived comfortably enough. (It must be stressed, though, that millions have not shared our relative ease. The legion tales of loss – of jobs, businesses, families, lives – will never be fully told.) Yet we yearn for release, for salvation from limbo land.

On the morning of April 1, the first full day of Shanghai’s lockdown, the faint, plaintive tones of the erhu wafted across the street. A woman on the rooftop terrace opposite to our building had started playing the traditional Chinese stringed instrument. Every day, now for more than 50 days, she has started playing at what would ordinarily be rush hour, sometimes continuing for hours per day. Her music civilizes the otherwise eerily quiet, dystopian neighborhood.

She sits on the rooftop terrace of a former hotel, repurposed in March 2020 as a quarantine center for inbound travelers. They’re bussed in from the airport to spend two weeks in their assigned hotel rooms, with monitors on their doors. Every arriving passenger from overseas, for the past two years, has done the same. The erhu player may be a traveler stuck in the hotel past her expected two weeks, now allowed to wander the property but not to leave – one shade lighter, but still a rather dark grey on the lockdown/release spectrum. Or she may be a staff member similarly stuck.

The former hotel sits on the corner of two of Shanghai’s usually busier streets. A few busses have started to venture out, after weeks when none were in sight. The waist-high caution taping around an entire block of small shops opposite our building has been removed, though the shops themselves remain closed.

By line of sight, the erhu player is only 100 meters away, five minutes’ walk from my front door. I wish I could cross the street to tell her how much her music has meant to me, and probably dozens of others. In the Before Time, I walked right in front of the building daily, but now it might as well be a distance of 100 miles, or 10,000. Even if I could leave the building to cross the street, I’d be barred from entering the quarantine facility.

She’s in limbo land too. Maybe she has a family waiting for her. Maybe she came to Shanghai to play in a concert that has long since been cancelled. I’ll never know.