Of the 14 small diplomatic allies that recognize the Republic of China (Taiwan), eight are in Latin America and the Caribbean. This is a region that has become one of the main arenas of the growing geopolitical dispute between China and the United States. The question of Taiwan’s diplomatic survival as a state has become central to China-U.S. relationship and Latin America will be a key region in that context.

China has made steady progress in recent decades in the region, becoming the top trading partner of most Latin American countries. At the same time, China’s investments and financial cooperation have also increased significantly, although this trend has recently shifted downwards. According to a Boston University report, for the second year in a row, in 2021 the China Development Bank and China Eximbank issued no new loans to the region. While this is very striking, it is still too early to draw conclusions, given the exceptional international context that has arisen in the wake of COVID-19.

At the onset of the pandemic, Chinese state-owned companies such as State Grid Corporation and Three Gorges acquired companies and projects in the electricity sector in Brazil (a BRICS member), Chile, and Peru. Both of the latter countries, located on the east coast of the Pacific Ocean, have signed free trade agreements with China and are members of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) promoted by Xi Jinping’s administration. This ambitious Chinese initiative has been quite successful in Latin America in terms of accessions: With the confirmation of Argentina, there are now 20 countries in the region that have joined the BRI.

The Taiwan issue has been at the center of Beijing’s interests in Latin America, as China seeks to increase the island’s diplomatic suffocation on a global scale and, in parallel, to annoy the United States in its historic backyard. China’s strategy has borne fruit, basically by dint of its unrivalled economic and financial attractiveness to Latin American nations.

To cite one of the most paradigmatic cases, it is worth recalling what happened with Costa Rica. In 2006, the People’s Republic of China donated a new national football stadium after Costa Rice broke off relations with Taiwan. Barely a year later, Costa Rica signed a free trade agreement with Beijing and important investment projects were announced with Chinese financing.

In the last five years alone, Taiwan has lost four allies in Central America: Panama (2017), El Salvador (2018), the Dominican Republic (2018), and Nicaragua (2021). In all cases, the severing of relations with Taiwan came hand in hand with grandiose announcements of Chinese investment and loans for these small countries, something Beijing has been able to cope with easily, given the gigantic asymmetries and pressing financial needs of these countries.

In the case of Panama, the announcement in 2017 of a $4 billion high-speed train project to be financed by Chinese banks stands out, although it is still under consideration. As for El Salvador, the break with Taiwan brought immediate commitments by Beijing to finance various infrastructure projects for some $500 million. For the Dominican Republic, meanwhile, China’s promise after the break with Taiwan was for initial loans of $3 billion, expandable to some $10 billion. Finally, in Nicaragua China can now relaunch its long-delayed Nicaragua Canal project under the isolated and economically stifled dictatorship of Daniel Ortega.

Other Central American countries are on the high wire, facing both pressure and seductive overtures from China. Perhaps the most notable case is that of Honduras. Following the victory of leftist Xiomara Castro in the 2021 presidential elections, all indications were that Tegucigalpa would also break off relations with Taiwan. Castro herself had hinted at this during the campaign. For now, however, Honduras remains aligned with Taipei, following a strong U.S. campaign to prop up Castro in power and guarantee the maintenance of the diplomatic status-quo.

The question is: How long can Honduras hold out? And, more broadly, how much longer will other, even smaller, countries in the region – those much more in need of economic assistance, such as Guatemala and Haiti – be able to remain aligned with Taipei?

In the pandemic, through so-called “vaccine diplomacy,” this imbalance in favor of Beijing became much more evident. An emblematic case was Paraguay, Taiwan’s only South American ally, which suffered from vaccine shortages at the worst moment of the pandemic. While neighboring countries received doses of Chinese vaccines – Sinopharm, Sinovac, and CanSino – Asunción had to resort to operations via Chile and other countries to gain access to vaccines.

Beijing made sure to convey that it would have been a different story if Paraguay had broken off relations with Taiwan. In his new book “Irruption: Logbook of a voyage in troubled waters” (2022), former Paraguayan health minister Julio Mazzoleni stated that the issue of vaccines was used by China as a “political, geopolitical and diplomatic instrument.”

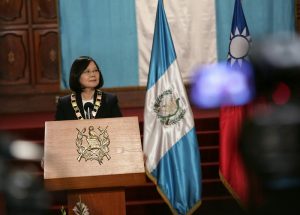

In response to China’s efforts, the Taiwanese government, in tune with the United States, has redoubled its efforts to halt the loss of allies by deploying substantial economic aid packages. But it is clear that this has not been enough to counter the unstoppable Chinese advance. Such efforts, meanwhile, have also had a cost for Taiwan’s image and its main sponsor, the United States. For example, it is worth recalling that former Guatemalan President Alfonso Portillo was sentenced in 2014 to five years and ten months in prison after he admitted to receiving $2.5 million in bribes from Taiwan and laundering money through U.S. banks.

It does not help Taipei’s interests that the hallmarks of its few remaining diplomatic allies in the region are low relative weight in the regional economy, high levels of corruption, institutional fragility, and high political volatility.

This means that, from Beijing’s perspective, it is only a matter of time before Taiwan’s remaining eight allies in the region – Belize, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Paraguay, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines – end up severing ties with the island and recognizing the People’s Republic. A priori, the only thing that could change this scenario would be an eventual Chinese withdrawal from the region (highly unlikely) or a renewed U.S. interest in intervening more actively to influence Taiwan’s allies (there are no clear signs in this regard, beyond limited actions).

The scenario is not encouraging for Taipei. Even while China seems to be recalculating its geopolitical priorities and even cutting back on financial assistance in the region, it takes very little for China to continue to take diplomatic allies away from Taiwan. On the other hand, unlike in Europe, where countries such as Lithuania have hinted at recognizing Taiwan, no country in Latin America has any real intention or possibility of doing so.

Finally, the time factor also plays in Beijing’s favor. China has no deadlines or specific goals in the race to continue gaining diplomatic allies. The Communist Party’s view is that Taiwan’s diplomatic isolation is a natural and irreversible process on the road to unification (peaceful or forced). In any case, Latin America will remain a central stage in Taiwan’s unequal struggle for diplomatic survival, with Taipei clinging more than ever to the indispensable lifeline that Washington can offer.

The article was first published in Spanish in Reporte Asia.