On May 12 and 13, the United States and Cambodia co-hosted the two-day U.S.ASEAN Special Summit in Washington, D.C., the second such summit to be held since 2016. Many issues were discussed during the meetings, ranging from the Myanmar crisis and the code of conduct in the South China Sea to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The U.S. also expressed its interest in elevating its relations with ASEAN to the level of a comprehensive strategic partnership. Given that Cambodia is the current chair of ASEAN, the ASEAN-U.S. summit also has implications for Cambodia-U.S. relations.

For the past 25 years, U.S. relations with Cambodia have been characterized by a war of rhetoric and suspicion on the part of the U.S., with the result that Cambodia has moved closer to China. The Biden administration appears convinced that Washington’s previous tough approach toward Cambodia is not working, and has taken steps to change in its approach. In late 2021, Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman visited three Southeast Asia countries, including Indonesia, Thailand, and Cambodia. Alongside two important U.S. partners, the inclusion of the stop in Cambodia was surprising, given that Washington has long viewed the country as China’s key ally in the region.

Though Sherman discussed a range of sensitive topics during her meetings with Cambodian officials, including the Chinese presence at Ream Naval Base, the visit itself demonstrated Cambodia’s strategic significance to the U.S. Cambodia is suspected by the U.S. of harboring Chinese military assets at the base, which is the only deep-water port in Cambodia. The visit took place just as Cambodia was about to take on the role of the ASEAN chairmanship. The visit was seen as a “confidence-building measure” in an atmosphere of mistrust, with the U.S. seeking to clarify why Cambodia had demolished the U.S.-funded facilities at the base and also requesting permission from the Cambodian government for the U.S. military attaché to visit Ream. The U.S.’ willingness to seek clarification on the navy base and Cambodia’s compromise in allowing the U.S. military attaché to visit the base demonstrated a willingness from both parties to resolve the mistrust.

Three months prior to Sherman’s visit, Cambodia suspended its bilateral military exercises with China, known as “Golden Dragon,” citing COVID-19 pandemic precautions as the main reason, despite the fact that there were no serious COVID-19 outbreak in the country by the day of the announcement. The halting of Golden Dragon paralleled the cancellation in 2017 of the Cambodia-U.S. military exercise known as “Angkor Sentinel,” which marked a low point in bilateral relations. In cancelling its two-week military exercises in March with China, Cambodia indicated to the incoming Biden administration its readiness to restore relations with the U.S. and dispel suspicions about the country’s over-reliance on China.

On May 11, one day before the U.S.-ASEAN Summit, Hun Sen arrived in the U.S. and had a meeting with over 2,000 Cambodian-Americans in Washington. He reiterated Cambodia’s neutrality by stating, “Our policy goes hand in hand with that of ASEAN’s. I want to draw a line in that, with any Indo-Pacific or Asia Pacific Initiative, Cambodia will abide by three principles: firstly, peace and development, secondly, taking no one as enemy, and thirdly, respecting ASEAN Centrality.”

Cambodia also released its third Defense White Paper just a day after Hun Sen’s arrival in the U.S. for the summit. The defense paper again emphasized Cambodia’s neutrality and independence, and, in line with the country’s Constitution, stressed that Cambodia would not allow foreign troops to be stationed on its soil. The Cambodian government’s simultaneous actions were not a coincidence but rather a double message to Washington that Cambodia does not intend to serve China’s strategic goal of countering the U.S. role in the Indo-Pacific.

Though there was no concrete outcome that demonstrates the strengthening of Cambodia-U.S. relations, the outcome of the summit has offered a reset in a troubled bilateral relationship. As mentioned, the summit also aimed to upgrade ASEAN-U.S. relations to the level of a comprehensive strategic partnership, something that Australia and China achieved in 2021. This willingness to deepen ties with ASEAN recalls the visit to Cambodia and Indonesia in late 2021 of senior U.S. diplomat Derek Chollet, during which he revealed to Cambodia’s Foreign Minister Prak Sokhonn the importance of ASEAN to U.S. foreign policy in the Indo-Pacific.

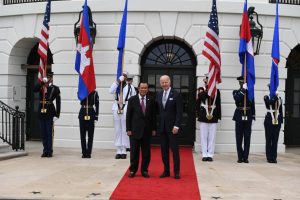

Against this backdrop, Phnom Penh is in a hurry to elevate this partnership before the ASEAN chairmanship passes to Indonesia at the end of the year. During the summit in Washington, Hun Sen personally invited Joe Biden to attend the ASEAN-U.S. Summit in Cambodia in November. All this signaled a role for Cambodia in contributing to stronger ASEAN-U.S. relations.

In conclusion, the U.S.-ASEAN Special Summit has not only contributed to ASEAN-U.S. relations but also helped to temper the tensions in relations between Washington and Phnom Penh after a long period of mutual suspicion and accusation. After the summit, Hun Sen declared that Cambodia-U.S. relations were “at their highest level” in decades. Yet, despite the optimistic rhetoric, relations between the two countries remain unpredictable, a result of conflicting interests and decades of mistrust, which will take more time to overcome, even if both sides are willing to let bygones be bygones.