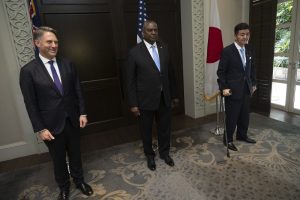

Over the weekend, the Australian, Japanese, and U.S. defense ministers met on the sidelines of the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore. The Trilateral Defense Ministers’ Meeting (TDMM) convened to much less fanfare than a meeting of Quad ministers attracts. The Trilateral and the Quad are not in competition; in fact, they are mutually reinforcing. But the Quad has received much more attention for its potential to deliver defense outcomes in the Indo-Pacific than the Trilateral, when the reverse is true.

The Trilateral will be far more significant for Indo-Pacific defense than the Quad could hope to be. Here’s why.

Consistency in cooperation and time under pressure has strengthened the triangle more than the diamond. The origins of the Australia-Japan-U.S. trilateral are older than the Quad, with 2022 marking two decades of cooperation. Starting at the senior official level in 2002, trilateral meetings were later elevated to foreign secretary (2006), leader-level (2007), and defense secretary (2010).

Around the same time Trilateral meetings were expanding to senior levels and new portfolios, the Quad was breaking up amid pressure from China. What led the Quad to disband in 2008 is disputed but, under the same geopolitical circumstances, the Trilateral consolidated. The Trilateral’s unbroken pattern of cooperation has built trust and familiarity while Chinese pressure has seen Australian, Japanese, and U.S. strategic interests converge even more closely.

Another primary reason the Trilateral stands to outperform the Quad in Indo-Pacific defense is simple: The Quad has dealt itself out of defense issues while the Trilateral embraces them.

There has never been a meeting of Quad defense ministers, whereas the last TDMM was the tenth iteration. At the TDMM, Australia, Japan, and the United States committed to expand cooperation on R&D, advanced technologies, and strategic capabilities, as well as to increase military interoperability. On the latter, they are advancing interoperability across all three services. The end of May marked the conclusion of their trilateral ground exercise, Southern Jackaroo; in March their navies trained together in the South China Sea; and in February they conducted aerial combat training via Exercise Cope North.

Contrast this with the Quad’s would-be equivalent maritime exercise, Malabar. Australia only recently re-joined Malabar in 2020 after more than a decade hiatus. Moreover, India rejects any connection between Malabar and the Quad to deliberately downplay a defense connection.

Beyond practical military cooperation, on key Indo-Pacific flashpoints and areas of concern – Taiwan, North Korea, and the Pacific – the Trilateral has a much greater strategic stake than the Quad.

Regarding Taiwan, the U.S., Japan and Australia have all made stronger statements in support of its defense in recent years and mentioned the security of the Taiwan Strait in the TDMM joint statement. The Quad Statement did not.

On the stability of the Korean Peninsula, the U.S., Australia and Japan have a shared history of active military commitments to South Korea – as recently as last year Australia had peacekeepers deployed to the United Nations Command on the Demilitarized Zone. Any military confrontation on the peninsula would activate U.S., Japanese, and Australian forces immediately and cause those countries direct consequences. By contrast, drawing Indian troops into a Korean Peninsula conflict as part of a Quad contingent would not be a natural solution, particularly given India’s non-aligned history.

On the Pacific too, Australia, Japan, and the U.S. are deeply concerned with China’s defense encroachment in this subregion and are mobilizing in response. To be sure, India is concerned about Chinese coercion and the risks to state sovereignty, but it has specifically avoided talking about the China-Solomon Islands pact. Pacific security does not represent an area of strong overlapping interest for the Quad because India is far removed from Pacific Island nations and Delhi has its own, higher priority challenges with Chinese influence in South Asia and the Indian Ocean.

In all of these flashpoint areas, the strategic rationale for the Trilateral to play a role is strong, but the rationale crumbles when broadened to Quad cooperation. This is also true at the global level.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, Australia, Japan, and the U.S. would have liked a robust Quad response but India’s military ties with Russia prevented any such action. The Quad statement from May 24 was so lukewarm on the issue it referred only to the “conflict in Ukraine” – not Russia’s invasion or war – and responded only that “the centerpiece of the international order is international law” and “all countries must seek peaceful resolution of disputes.” While the Trilateral countries were on the same page, India’s differences with its Quad partners were exposed.

There should be no quarrel that the Quad is an ambitious and promising security mechanism. Yet, as a grouping that will bring about solid defense and strategic outcomes in the region, the Quad cannot compare with the slimmed down Trilateral. Last weekend’s TDMM went almost completely unreported, but the Australia-Japan-U.S. trilateral deserves the envy of the Indo-Pacific. For, while the Quad gains all the attention, the Trilateral is quietly achieving in the background.