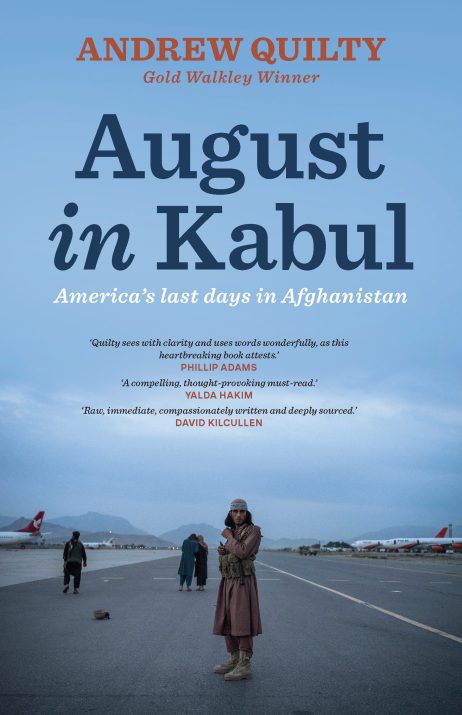

Journalist Andrew Quilty, who spent much of the last decade in Afghanistan, returned to Kabul on August 14, 2021. The United States’ longest military adventure was nearing its conclusion, but the collapse of the Western-backed government of Ashraf Ghani was swifter than any imagined possible. Within days, the reality of life in Afghanistan changed. In his book, “August in Kabul: America’s Last Days in Afghanistan,” Quilty follows a cast of Afghans — a young woman with ambitions to be a lawyer, an Afghan officer, a staffer in the doomed administration, an escaped prisoner — through that fateful month. In the following interview, Quilty tells The Diplomat’s Catherine Putz about the choices he made in writing this part of Afghanistan’s story and what is most important to know now: That the end of the war does not mean Afghanistan is at peace.

The book, which is arranged chronologically, uses various voices to tell the story of Afghanistan in August 2021. Tell me a little about your decisions regarding the structure of the book and the selection of characters which inhabit it.

The book, which is arranged chronologically, uses various voices to tell the story of Afghanistan in August 2021. Tell me a little about your decisions regarding the structure of the book and the selection of characters which inhabit it.

I had a rough idea of the kinds of characters I wanted to find in order to best provide a diverse range of perspectives on the events of those days. It was particularly important for me to be able to describe this tumultuous time from both sides of the conflict. The Taliban’s victory made this more achievable than ever; whereas once their fighters lived in hiding, deep in areas that were extremely difficult and dangerous for outsiders to reach, now they were happy to talk and their districts and provinces were open and relatively safe to travel to.

It was the characters and their experiences of the time that dictated how the book was structured. I thought it was important to include a chapter describing what happened in Afghanistan’s rural areas in the lead up to the collapse of Kabul, and so I searched long and hard for people who could provide that point of view to open the book.

For the remainder of the book, set in Kabul, I wanted to jump from one character to the next, offering personal insights into some of the significant events – the chaos inside the presidential palace, desperation and despair at the airport, the sense of liberation for Taliban inmates being freed from Bagram prison – in the days leading up to the Taliban’s arrival, through to the final departure of the Americans.

In the epilogue you mention that after conducting nearly 100 interviews, the book was “taking a vastly different form to the one I’d expected to write just a couple of months earlier—and necessarily so.” Were there any interviews in particular that shifted your framework? What had your original expectations been when you began this project?

As I mention in the epilogue, I had expected to write a book about why it came to the point of collapse for the Afghan government and shame for the U.S.

That book can be written in the future, though, once the dust has settled. It has already been written, in fact, many time over, over the past decade.

What I could contribute, having been present at the time of the Taliban’s return, was a more immediate, human story, of how those most affected by it experienced this period.

In the first two weeks of August, as cities and districts fell to the Taliban, how did the mood change in Kabul? And how did the efforts of the Americans and the Afghan government change?

I was actually in France those two weeks, until August 14, so I can only tell you what I was hearing from friends. I also write about this in the prologue.

As for the Americans, their efforts to wind up military operations were already in full swing – they already had the August 31 withdrawal deadline to work toward, after all. The diplomatic mission, however, was hoping to remain and only began to seriously reconsider this as the Afghan government’s ability to remain in control crumbled. They went from downsizing their footprint to mitigate risk, to closing the embassy entirely.

What is it most important for people to know about Afghanistan now, a year after the collapse of the government, the withdrawal of U.S. and NATO forces, and the coming to power of the Taliban?

That the end of the war does not necessarily mean Afghanistan is at peace.

In the author’s note, you write that “despite the warnings almost every Afghan I spoke to gave me about distrusting the Taliban’s conciliatory rhetoric, I wanted to believe them.” Arguably, you are not alone in that. What would you say to those who still want to believe conciliatory Taliban rhetoric, despite all that has happened?

There are elements within the Taliban who are more reformist minded than their more conservative founders, many of whom still hold sway leadership positions. However, I think, by now, it’s clear that the Taliban’s pre-takeover conciliatory rhetoric was just that: rhetoric.