When the United States stumbled out of Afghanistan in mid-August 2021, President Joe Biden said that Washington would “maintain the fight against terrorism in Afghanistan and other countries.” He said the U.S. would retain “over-the-horizon capabilities” to strike “terrorists and targets.”

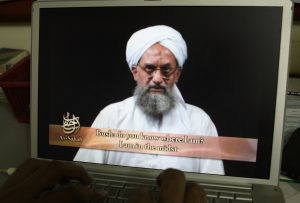

Nearly a year later, al-Qaida leader Ayman al-Zawahiri was killed in a U.S. drone strike in a Kabul. The strike on July 31 was initially reported by the Taliban Interior Ministry to have been a rocket hitting an “vacant house” in the Sherpur neighborhood. But reports soon surfaced that the target had been al-Zawahiri, a fact confirmed by Biden on August 1.

A Taliban spokesman condemned the strike on August 1 and called it a violation of “international principles” and the 2020 Doha agreement.

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken in his August 1 statement about the death of al-Zawahiri was unequivocal, calling out the Taliban for violating the Doha agreement: “By hosting and sheltering the leader of al Qa’ida in Kabul, the Taliban grossly violated the Doha Agreement and repeated assurances to the world that they would not allow Afghan territory to be used by terrorists to threaten the security of other countries.”

Once again, the Taliban and Washington have divergent interpretations of the February 2020 agreement settled between the Trump administration and the Taliban, which ostensibly was to pave the way for a U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and a negotiated peace between the Taliban and the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. The five-page agreement, labeled as “comprehensive” by the Trump administration, was anything but; its terms were too good to be true.

In June 2020, mere months after the agreement, a U.N. report claimed that the Taliban had not cut ties with al-Qaida. At the time, Saurav Sarkar noted in an article for The Diplomat, “The Taliban-al-Qaida alliance has survived the deaths of bin Laden and two Taliban emirs, which is indicative of something much deeper than personal relationships at the top level.” That violated the Taliban’s end of the bargain. The following year, after a tumultuous election cycle in the United States dumped Trump from office, Washington pushed back its withdrawal date — originally May 2021 — which the Taliban decried as a violation of the agreement. When the Taliban pushed into Kabul in August 2021 and the Western-backed government of Ashraf Ghani collapsed, the Doha Agreement was in tatters. And yet, both the U.S. and Taliban still call upon it as a point of reference.

The Taliban, indeed, did not abandon the relationship with al-Qaida; or at the very least the Haqqani Network, a powerful faction within the Taliban, did not. As the Associated Press’ Rahim Faiez and Munir Ahmed reported, al-Zawahiri was killed in an “upscale” Kabul neighborhood. According to the AP, citing a senior U.S. intelligence official, the “house where al-Zawahri stayed was the home of a top aide to senior Taliban leader Sirajuddin Haqqani.”

Just as it was hard to fathom that the Pakistani government was unaware of Osama bin Laden’s residing in Abbottabad when the U.S. staged a dramatic cross-border raid to kill him in 2011, it’s difficult to believe that the Taliban were unaware of al-Zawahiri living in a safe house in the middle of Kabul.

The killing of al-Zawahiri won’t alter the nature of relations between the U.S. and the Taliban, but it might stoke internal tension for the Taliban — if indeed some leaders where aware, and others were not. For the U.S., although al-Qaida’s power is much diminished from two decades ago, the strike demonstrates a usable capability to strike targets when and where Washington wants to.