Yesterday, Reuters published an exclusive report revealing the Vietnamese government’s plans to tighten further its grip on flows of news and information online. According to the report, the ruling Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP) is preparing new rules to limit which social media accounts can post news-related content.

The rules, which the report said are expected to be finalized by the end of 2022, would establish a legal basis for controlling the dissemination of news on platforms like Facebook and YouTube.

As social media use has boomed in Vietnam – the country has the seventh-largest pool of users in the world, in addition to 60 million YouTube users and 20 million on TikTok – the government has attempted to place it under firm state control – to nail the Jell-O to the wall, in former U.S. President Bill Clinton’s famous (mis)characterization.

Among its many concerns, the Vietnamese authorities are worried about privately operated social media accounts misleading users into thinking that they are authorized news outlets. Under its proposed regulations, the Reuters report stated, the VCP would be able to order social media companies to ban accounts that transgress its regulations.

While they are yet to be finalized fully, the regulations mark an intensification of the government’s attempt to migrate legacy media controls to the freewheeling online space, and would add to the already significant moderation burden on social media platforms.

In July, Reuters reported that Vietnam’s government had introduced a new national social media “code of conduct,” which encourages its people to post positive content about the country and prohibits anything that violates the law or affects “the interests of the state.” The following month, Vietnam also issued a new regulation that will require technology firms to store users’ data locally and to set up local offices, which will come into effect tomorrow (October 1).

The Vietnamese government has already pushed social media platforms to remove content that it deems subversive or “anti-State,” leveraging the fact that the country produces an estimated $1 billion in annual revenue for Facebook’s parent company, Meta. In April 2020, Facebook announced that it had agreed to “significantly increase” its compliance with requests from the Vietnamese government to remove posts that it deems “propaganda against the Party and the State.” Six months later, a minister told Vietnam’s parliament that Facebook was approving 95 percent of the government’s requests to block content, while YouTube complied 90 percent of the time.

In a report published in late 2020, the advocacy group Amnesty International claimed that Facebook and YouTube are complicit in “censorship and repression on an industrial scale” in Vietnam.

As the latest Reuters report makes clear, even this level of cooperation does not rise to the level desired by the Vietnamese authorities. Citing sources familiar with the issue, the article stated that the country is soon expected to “implement new rules that would require social media platforms to immediately take down content deemed to harm national security, and to remove illegal content within 24 hours.”

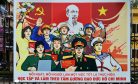

While, unlike its Chinese counterpart, the VCP appears either unwilling or unable to block these social media networks entirely, it is nonetheless bent on reducing its potential to mobilize political opposition and ensuring that it supports, rather than undermines, the Party’s nucleal position in the Vietnamese state.