The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) did not issue a message of condolence on the death of former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Not that it was expected to. The CCP regarded Gorbachev as a “gravedigger,” as Deng Xiaoping called him, and has used a stream of insults – “manipulator,” “villain,” “traitor,” and “murderer” – to describe the last Soviet party leader.

Since Xi Jinping does not have a dedicated spokesperson, either as the CCP general secretary or the president of the People’s Republic of China, a curt and cryptic statement issued by the Chinese Foreign Ministry provided the official response from Beijing. “Mr. Gorbachev made positive contributions to the normalization of China-Soviet Union relations. We mourn his death and express our condolence to his family,” the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson said.

The news of Gorbachev’s death has been widely reported in China’s official media, but most media outlets merely repeated the Foreign Ministry spokesperson’s tepid remark. At the same time, while not quite in line with the party’s current stance of not encouraging undue attention to the late Soviet leader, quite a few national-level media agencies did publish commentaries on how Gorbachev “spiritually surrendered to the West” and his “naïve,” “premature” perestroika policy was manipulated by Boris Yeltsin first into a coup, which eventually ended in the disastrous collapse of the Soviet Union.

In the words of Tsinghua University academic, Xie Maosong, “China’s decades-long economic success has shown the country has moved on and there is no point in discussing Gorbachev.”

Both in the West and in Putin’s Russia, evaluations of Gorbachev’s six years (1985-91) at the helm of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) remain highly ambivalent and contested. In contrast, the communist leaders in Beijing have a clear consensus. Since Deng Xiaoping, CCP officials have consistently maintained that Gorbachev’s desire to reform the stagnating Soviet economy was well-intended, but he failed to retain the leading role of the CPSU over society.

A political science professor in Beijing who did not want to be named, recalled, “In the 1980s, the CCP and CPSU had arrived at the common understanding that the old [communist] system had failed.” Gorbachev sincerely, yet naively, embarked on the path of abandoning communist ideology in favor of liberal democracy, which was incompatible with the Soviet Union’s structure and thus crystalized into a cycle of domestic crises.

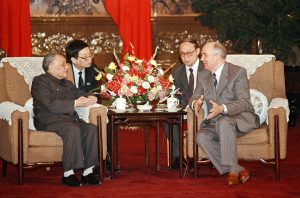

At another level, it is rather strange that very little has resurfaced in both the Chinese media and in the mainstream world press about the late Soviet leader’s now famous visit to China in May 1989, amid the student protests in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. While Chinese leaders were conspicuous in their enthusiasm to warmly welcome Gorbachev for his initiative to normalize relations with Beijing, what was then hidden from the media was that internally the party was nervous. Then-Chinese premier Zhao Ziyang had angered Deng Xiaoping with Zhao’s keen desire to initiate Gorbachev-style internal party restructuring. The rumors of a chasm at the highest level within the CCP leadership were later confirmed with the ouster and house arrest of the premier days after Gorbachev left the Chinese capital for Moscow.

Notwithstanding claims made by a section of the Chinese intelligentsia that the CCP has moved on from the events of 1991, it is nonetheless true that “study classes” within the CCP and serious political debate in academia on the causes of the Soviet collapse continue unabated to date. Perhaps as a chilling reminder for the CCP leaders, the fear of one person causing the state and party to dissipate overnight was manifested in the title of an article uploaded two days after Gorbachev’s death on one of China’s most influential leftist digital platforms: “Preventing the emergence of Gorbachev-like leaders is the only cure.”

Since assuming power in October 2012, Xi himself has on numerous occasions summoned senior-level party cadres and “indoctrinated” them against “seeking an independent way” and “worshipping the West.” Within a few months after Xi was anointed the PRC president in March 2013, party and state officials from across the country were called in to watch a long documentary at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, “In Memory of the Collapse of the Communist Party and the Soviet Union.” The central message of the four-part documentary was to warn the CCP cadres against Gorbachev’s blind move to introduce Western-style democratic reform.

At the same time, since taking command of the CCP a decade ago, Xi has been tightening political control and strengthening the role of public enterprises in the economy. In other words, under Xi, the CCP has been consolidating the party’s primacy in every sphere of life. And, as has been witnessed more recently, the party has been cracking down on the private capital and individual wealth under the slogan “common prosperity” on one hand. On the other hand, the CCP has unleashed a political campaign against “historical nihilism” in order to maintain its ideological monopoly.

According to Christopher Vassallo, a China analyst at Blackstone, during Xi era, there has been a fundamental shift from emphasis on economic or leadership failure as the causes for the Soviet Union’s demise to more nebulous concepts of cultural, societal, or “moral” decay.

According to a summary of Xi’s political remarks – initially for the party’s inner circulation but eventually published in the CCP theoretical journal Qiushi (Seeking Truth) three years ago – Xi once asked the party officials, “The Soviet Communist Party had 200,000 members when it seized power; it had 2 million members when it defeated Hitler; it had 20 million members when it relinquished power. Why? For what reason?”

Xi answered his own question: “Because the ideals and beliefs were no longer there.”

One of the important lessons the CCP has learned from the collapse of the Soviet Union is to prevent the emergence of a leader like Gorbachev. Pieces of the party might become corrupted, but as far as CCP leaders are concerned the Soviet model itself was perfect.

Deng’s famous “southern tour” to Shenzhen in January 1992 aimed at reasserting China’s commitment to opening up and reform in the wake of the Soviet collapse. A couple of weeks into his tenure as CCP leader, Xi undertook his own “southern tour” to Shenzhen to reassure his commitment to continue reform. While in Shenzhen, addressing a select gathering of party officials, Xi said: “I would not repeat the mistake of Mikhail Gorbachev. I promise to reform and not shake the regime.”

But if the CCP or Xi Jinping are serious about learning from history – as Marxists profess they are– they have not yet shown any sign of having learned a key lesson from the Soviet Union’s dissolution: It is impossible to imagine holding one person solely responsible for the collapse of a superpower.