On October 4, the Japanese government reported that North Korea fired a ballistic missile over its airspace, with the missile subsequently landing to the east of northern Japan in the Pacific Ocean. This was North Korea’s 37th ballistic missile test this year, but the first North Korean missile to violate Japanese airspace since 2017. The October 4 intrusion caused alarm amongst Japan’s residents in the rocket’s flightpath and ignited fierce indignation in Tokyo, with Prime Minister Kishida Fumio condemning the launch.

While there were no injuries or property damage reported during the incident, there is no guarantee that will be the case during any future missile demonstration over Japan. Such provocative overflights could result in deadly debris raining on innocent civilians – to say nothing of the possibility of Pyongyang purposely targeting Japan in a future conflict.

Since Kim Jong Un appears hell-bent on growing North Korea’s nuclear and missile arsenal, with neither diplomacy nor sanctions offering decent prospects for freezing or rolling back the North’s missile and WMD programs, it would be prudent for Tokyo to prepare for the worst by beefing up the Japanese Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) architecture. This would allow the government to shoot down incoming North Korean missiles, whether nuclear tipped or not, which threaten Japanese lives or crucial infrastructure.

To be sure, Japan is not defenseless against missiles from North Korea. The five landmasses comprising the Japanese home islands of Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu, and Okinawa are protected by a BMD system that constantly screens for incoming missile threats using a developed integrated network of radars and satellites along with airborne and sea borne sensors. Data from this network is then relayed to a command-and-control system dubbed the Japan Aerospace Defense Ground Environment (JADGE), which will determine possible impact areas (if any) and can immediately direct sea- or land-based BMD interceptors to destroy the incoming threats.

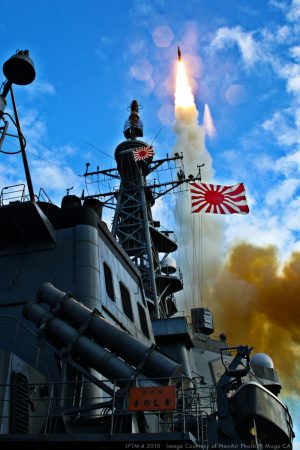

Currently, Japan’s stable of BMD missile systems include those operated by the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF), Japan Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF), and Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (JGSDF). The JMSDF deploys SM-3 and SM-6 missiles controlled by Aegis radar and missile control systems onboard suitably equipped Maya-class, Atago-class, and Kongo-class destroyers to intercept short and intermediate ranged missiles. As for land-based BMD, the JASDF operates Patriot PAC-3 missiles while the JGSDF utilizes the Type-03 medium-range surface-to-air missile. The former are able to intercept short and intermediate range missiles, while the latter are capable of shooting down low flying cruise missiles.

Japan currently is planning to add two new Aegis-equipped ships to the JMSDF’s existing eight Aegis destroyers, despite concerns within Japan about the cost and manpower requirements. Aegis-equipped destroyers are extremely costly, with some estimates reporting a total price tag of 900 billion yen for the two new ships. Meanwhile, such vessels costs a great deal to maintain, operate, and crew.

It might be more cost effective to procure more Patriot PAC-3 systems, continually upgrade all Patriot units in service, and endeavor to provide all cities with 500,000 or more inhabitants with missile interception protection. Additionally, more Type-03 batteries should be bought and operational crews trained in order to bolster cruise missile defense for population centers, military bases, and vital infrastructure closest to North Korea.

Enhancing Japan’s BMD framework makes political, economic, and even tactical sense. To begin with, the prevention of casualties is politically paramount. The Kishida administration can frame the extra BMD strengthening expenditure in terms of the desire to prevent North Korea from wreaking havoc on civilians, like Russia is now doing to Ukrainians. Moreover, this move is geostrategically defensible as it is non-offensive and does not contribute to regional tensions or arms races. Japanese left-wing pacifists should not be able to oppose such a move as it fits within the non-expansionist spirit of the Japanese Self-Defense Force (JSDF).

Next, growing the land-based BMD architecture is economically reasonable since the potential lives saved from future missile contingencies makes the costs seem like a fair bargain. Also, raising air defense units is arguably less personnel intensive than equivalent land units like infantry or combat engineers. Given Japan’s greying population, shrinking youth demographic, and resultant recruitment challenges for the JSDF, BMD improvement would be more doable and incur a more sustainable personnel wage bill.

Lastly, despite the imperfect nature of missile defense, ramping up these capabilities provides concrete national security benefits. During a conflict, North Korea will have to divide its missile attacks between South Korea, U.S. territories like Guam, and Japan. Considering that North Korea is impoverished and thus limited in the absolute number of serviceable medium- and intermediate-range missiles it can allocate to hurt Japan, there is a decent chance that the latter’s missile shield might not have to withstand a missile deluge, thereby serving as a practical bulwark against Pyongyang’s potential aggression.

Growing Japan’s BMD system is not a quick endeavor. It will take years rather than months. Considering Pyongyang’s proclivity for military adventurism and brinksmanship, it would behoove Tokyo to be ready for any future missile escalation. Though it may sound trite, preventing casualties from the North’s missiles is far preferable to enduring missile barrages while waiting for South Korean and U.S. counterstrikes to “cure” the crisis.