In Kabul’s Dashti Barchi neighborhood on September 30, an all-too-familiar scene: a suicide bombing targetting not just civilians, but children. The attack at the Kaaj education center, where around 300 recent high school graduates were sitting for a practice exam, killed at least 25, according to the Afghan Ministry of the Interior, with one witness telling The Associated Press that the number was more like 40.

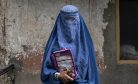

It was another tragedy in the largely Hazara neighborhood, and another tragedy for Afghanistan’s women.

Among the students taking the practice exam at the Kaaj education center, a private tutoring operation, were many girls striving for education despite every possible challenge. After taking power last year, the new Taliban government shut women and girls out of secondary education, with empty promises of eventually letting them return. While women were permitted to continue attending, and teaching, at the university level the restrictions are harsh: Women must cover themselves and cannot teach or be taught by men nor attend classes with men. The banning of girls in most of Afghanistan from attending public secondary schools cut off, for many, the pathway to university. But private institutions like the Kaaj education center, and certain communities like that in Dashi Barchi, were helping girls move ahead with their educational ambitions.

But school is not a safe place in Dashti Barchi. Back in April, multiple bomb blasts outside a high school and an education center in the neighborhood — the all-boys Abdul Rahim Shahid high school and the nearby Mumtaz Education Centre — killed six and injured 20. The previous year, in May 2021, another bombing at a school in Dashti Barchi killed at least 50.

To add insult to injury, in the days after the recent school bombing women taking to the streets to protest have been beaten back by the Taliban. In Kabul, a protest by women was violently broken up by the Taliban. Similar protests occurred in Herat and Bamyan.

The Taliban government’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs denounced the attack, with a deputy spokesman saying, “The Islamic Emirate does not believe in the religious, ethnic, or political divide of Afghan nationals and considers itself accountable for the lives of all Afghans.”

One demonstrator in Kabul told The Associated Press, “We are asking the Taliban government, when they claim that they have brought security, how they cannot stop an attacker from entering an educational center to target female students. In this incident, one family has lost four members, why is it still happening?”

The recent attack and response to protests expose the persistent insecurity in Afghanistan. While violence stemming from war may have diminished, sudden and arbitrary death remains a risk for Afghans attending school, going to the mosque, or walking down the street. Those risks are amplified for Afghanistan’s minorities and the country’s women.

The Islamic State Khorasan (ISK) is assumed to be responsible for the recent attack, as it has claimed responsibility in previous attacks targeting Hazaras. The group’s ability to stage attacks in the Afghan capital underscores the Taliban’s inability to control terrorist groups operating on Afghan soil. It’s a difficulty the previous Afghan government also struggled with, despite far greater external assistance and capacity.