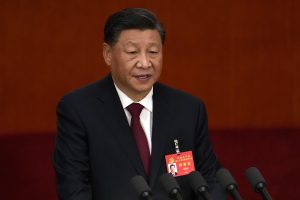

The 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) opened on Sunday, with CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping delivering a work report on behalf of the 19th Central Committee. The biggest takeaway from the speech was its signal of strong continuity, indicating a “steady as she goes” approach on everything from economic policy to diplomacy – despite increasing challenges and pressures on China.

Indeed, the overall theme of the work report was triumphalist, acknowledging the “severe and complex international situation” as obstacles overcome in pursuit of “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” Xi repeated the language from the seventh plenum last week that the past five years have been “extremely unusual and extraordinary.” The sentiment that the world is undergoing “big changes not seen for a century” was cemented in the work report, yet it also claims that the party overcame those difficulties to claim “historic victories,” including achieving a “moderately prosperous society” as of the CCP’s centennial in 2021 and eliminating extreme poverty.

Now the party moves on to a new “central task”: to achieve the “second centenary goal of building China into a great modern socialist country in all respects and to advance the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation on all fronts through a Chinese path to modernization.” As the name suggests, this goal is tied to the 100th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China – which would be 2049 – but Xi has pushed the date for “basically” realizing this goal forward to 2035. Conveniently, that leaves the door open for Xi to still be in command of the party at the big celebration 13 years from now.

Prior to the Party Congress, I highlighted five things to watch for in the work report. Now that we have the report, let’s take a look at those five points.

1. Zero COVID Is Here to Stay

As expected, Xi praised China’s approach to the COVID-19 pandemic, including its “unswerving insistence to dynamic zero.” He also said that the handling of the epidemic has had “significant positive results for economic and social development.”

It was to be expected that China’s insistence on zero COVID – a policy direction that has been closely tied to Xi Jinping personally and is therefore unassailable – would be held up as a positive. That said, it would have been possible to also address the downsides of that policy, even obliquely as sacrifices made for the greater good. Instead, the preferred narrative is that China’s COVID-19 policy is good for the economy. The refusal to acknowledge any economic toll from the zero-COVID approach sends a strong signal that these policies are not going anywhere.

Party Congress spokesperson Sun Yeli made similar comments in his press briefing, saying that China’s commitment to zero COVID has actually ensured economic stability by keeping the infection count low. “Our epidemic prevention measures are the most economical and effective,” Sun insisted, adding that “persistence is victory.”

2. China Learns to Live With Slower Growth

On economic policy more broadly, all indications are that China will stay the course. Old slogans like “dual circulation” and “supply-side structural reforms” reappeared. These reform efforts have been repeatedly mentioned since Xi took power in 2012, but the CCP has seen very limited success in shifting China’s economic model toward one based on domestic consumption and higher value-added products.

The slogan of “common prosperity” also appeared in Xi’s work report, which signaled a new focus on reducing economic inequality. The insistence on “high-quality development” goes along with the tacit acceptance that China is entering a period of slower economic growth, something the leadership seems willing to accept as long as individual households are still seeing their prosperity rise.

How, exactly, the CCP plans to reduce inequality remains uncertain, as the general policy prescriptions Xi mentioned have been tried again and again. Particularly curious is the tension at the heart of Xi’s “common prosperity” bid: He continues to both emphasize the need for a social safety net while also disparaging the idea of welfare as encouraging “laziness.” Instead, he is focused on increasing employment-based income. “We will ensure more pay for more work and encourage people to achieve prosperity through hard work,” Xi said. How that meshes with growing youth unemployment and the need for pensions for China’s surging population of elderly retirees is an open question.

Overall, Xi is more interested in security and stability than economic growth in and of itself – even China’s drive to cement a leadership position in high tech fields is framed as a national security imperative, necessary to reduce reliance on foreign technology. As Taisu Zhang, a professor at Yale Law School, noted in his analysis, stability has been elevated “to an end-in-itself, as opposed to merely a precondition for economic growth.” Words like “economy,” “reform,” “innovation,” and “opening” have all seen steep drop-offs in use compared to the final work report given by Hu Jintao in 2012, while “security” and “fight” have increased in frequency.

Sara Hsu made a similar point in The Diplomat earlier this year: “If it wasn’t clear before COVID-19 hit, it is now apparent that Xi Jinping, China’s top leader, does not prize economic growth above social and political factors.”

3. Xi’s Approach to Taiwan

On Taiwan, the big headline was that Xi reiterated China’s willingness to use force to incorporate Taiwan into the People’s Republic. “We will continue to strive for peaceful reunification with the greatest sincerity and the utmost effort, but we will never promise to renounce the use of force, and we reserve the option of taking all measures necessary,” he said.

“The complete reunification of the nation absolutely must be realized, and it absolutely can be realized!” Xi proclaimed.

China has never renounced the option of using force to annex Taiwan, but in high-level policy speeches leaders usually prefer to emphasize China’s preference for “peaceful reunification.” In that context, it’s notable that Xi explicitly said this warning was “aimed at interference by external forces and the extremely small minority of ‘Taiwan independence’ splittists.” In other words, Xi was giving a high-profile warning to the United States and the administration of Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen.

And in case anyone in the Biden administration missed the point, Xi reiterated his opposition to any foreign involvement in the Taiwan issue, insisting that “resolving the Taiwan question is a matter for the Chinese, a matter that must be resolved by the Chinese.”

Xi’s actual speech at the Party Congress was only an abridged version of the complete work report. Interestingly, the full version did include the usual references to the “1992 Consensus” and “One Country, Two Systems” as the baselines of China’s Taiwan policy. But it’s notable that the topline summary in Xi’s speech left those out, preferring to focus on its warning tone rather than offering any positive vision for cross-strait relations.

4. Whither the Belt and Road?

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), once the signature foreign policy for China, has seen something of a downgrade of late, and the work report continued that trend. The BRI did make an appearance in the summary of China’s accomplishments over the past five years, with Xi praising it as a “much welcomed… platform for international cooperation.” It was also briefly mentioned in the (very short) section on continuing to push forward China’s opening toward the outside world.

But it was the newer Global Development Initiative and Global Security Initiative that were mentioned by name in the broader section on China’s foreign policy. The BRI did not appear in this section, suggesting once again that it is being relegated to a lower place in China’s foreign policy hierarchy.

5. China’s Strategic Window

As I mentioned in my work report preview, for the last 20 years China has considered itself to be in a “period of important strategic opportunity for development.” But amid the challenges of recent years – not least a U.S.-led campaign branding China as a strategic competitor and security threat – that perception has changed. According to Xi’s work report, China is now in a period where “strategic opportunity and risks and challenges co-exist.”

Xi warned of darker times ahead, as China’s development enters a period where “uncertainty and unpredictable factors are increasing” and “all types of ‘black swan’ and ‘gray rhino’ incidents can occur at any time.” China must therefore “be ready to withstand high winds, choppy waters, and even dangerous storms.”

How will China do that? By sticking even more closely to Xi’s leadership, of course. Xi made repeated references to the “centralization” and “unity” of the party’s top leadership, both as a positive achievement of the past five years and as a process that will continue into the future.

The work report emphasized that the internal work on party-building was not done, with Xi aiming to continue to the fight to counter corruption and ideologically indoctrinate China’s people. Strict self-governance of the CCP is always a work in progress, Xi proclaimed, and he sternly warned fellow party members against a mood of “relaxation or rest, fatigue or war-weariness.” After all, the new era calls for a “new great struggle.”

While Xi will get his third five-year term as the CCP’s top leader, he’s still not done consolidating control and stamping out dissent. And he will use the external pressures facing China on all fronts as the rationale for tightening his grip over the party even further.