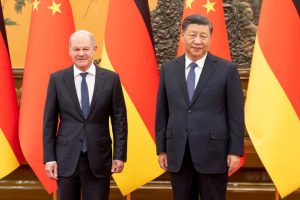

Germany’s Chancellor Olaf Scholz arrived in China on Friday, making him the first leader of a G-7 state to travel to China since the COVID-19 pandemic began. It was a whirlwind visit: Lasting just 11 hours, it was the shortest trip ever to China by a German leader.

The trip was steeped in controversy well before Scholz’s departure, with both coalition partners at home and other European governments raising concerns about a potential regression back to the Merkel era, when Germany prioritized economic ties with China over confronting threats posed by Beijing’s attempts to remake the global order.

Particularly concerning to many observers, Scholz was accompanied by what the the Economist described as “12 CEOs of German blue-chip firms, including the bosses of Merck, a drug company, Siemens, an engineering behemoth, and Volkswagen, Europe’s biggest carmaker.” That alone suggested a return to the “business-first” approach under Scholz’s predecessor.

Further worrying observers, in late October Scholz approved a deal for China to purchase a partial stake in Germany’s Hamburg port – despite deep opposition from his own ministers and from foreign partners like the United States.

Scholz defended his trip as being a conduit “for a candid and frank exchange with China” in a pre-departure op-ed published in Politico. The op-ed started with an acknowledgement that “[t]oday’s China is not the same as the China of five or ten years ago… the way that we deal with China must change too.” However, he added, “Even in changed circumstances, China remains an important business and trading partner for Germany and Europe. We do not want to decouple from it.”

As a sign of the fine line the chancellor is trying to walk, Scholz also promised to continue efforts to reduce “risky dependencies” on China and pledged to address sensitive issues like human rights, Xinjiang, and Taiwan.

Scholz’s op-ed also made clear that one if his biggest priorities was addressing the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, in the hopes of winning some shift in what has been termed China’s “pro-Russia neutrality.” In a press conference after his meeting with Xi, Scholz told reporters that he had told the Chinese leader that “it’s important for China to exert its influence on Russia.”

Accordingly, perhaps the biggest takeaway from the meeting was Xi’s direct mention of opposition to the prospect of nuclear weapons being used, a concern that has risen in the West amid ominous rhetoric from Moscow. The world must “oppose the threat or use of nuclear weapons, advocate that nuclear weapons cannot be used and that nuclear wars must not be fought, and prevent a nuclear crisis in Eurasia,” according to a readout of the Scholz-Xi meeting from China’s Foreign Ministry.

Andrew Small, a senior transatlantic fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States and an expert on China’s foreign policy, cautioned against seeing this as a major change from Beijing. “But now China can accrue credit, and be treated as the more ‘responsible’ power, for making statements that were treated as boilerplate a few months ago, and without having to follow through on them,” Small said.

“Indeed, this is deemed a success from the Scholz visit, so low is the bar now.”

Sure enough, as the Chinese readout makes clear, China’s overall position on the war has not changed. Xi repeated past calls for all parties to “exercise restraint” and pursue peace talks without ascribing any responsibility for the conflict. He also reiterated the need “to build a balanced, effective and sustainable security architecture in Europe,” echoing a Russian complaint that the existing security order in Europe, centered on NATO, is overly antagonistic. Moscow used that argument to justify its invasion of Ukraine.

Despite growing tensions between China and European countries over Beijing’s lackadaisical approach to the war in Ukraine, China is keen to avoid a united front between the United States and Europe. Chinese leaders hope to keep Europe neutral, an alternative “pole” in the multipolar order Beijing wants to craft. Not incidentally, keeping Europe neutral would also ensure China’s access to European research and goods that can help advances Xi’s new focus on cutting-edge tech.

Accordingly, Xi urged Scholz to “resist disturbance from bloc confrontation and attempts to see everything through the prism of ideology” while also calling for “China and Germany [to] respect each other [and] accommodate each other’s core interests.” He praised past “generations of Chinese and German leaders” for their stewardship of the relationship, implying that improving ties is an act of “extraordinary vision and political courage.”

Xi also recommended that “efforts should be made to energize cooperation in emerging fields such as new energy, artificial intelligence and digitalization.” Despite Xi’s hopeful tone, that prospect looks dim, considering the alarm with which leaders across Europe view China’s attempts to leapfrog the West in technological development.

Notably, there was no mention in the Chinese readout of real issues in the relationship, from Berlin’s longstanding dissatisfaction with the state of China’s “opening up” to human rights concerns. Scholz, however, told reporters that he had brought up human rights and market access, while also telling Xi that any change in the status of self-governing Taiwan “can only happen peacefully and by mutual agreement.”

Overall, the tone from Chinese state media was triumphalist; Beijing clearly sees Scholz’s visit as a feather in its cap, and an indication that transatlantic unity on China policy may be cracking. Whether that proves true, however, is not certain. Figures from the CDU, Germany’s major opposition party, and even within Scholz’s own ruling coalition have been outspoken on the need for a change in Germany’s approach to China.

Ahead of Scholz’s trip, CDU politician Norbert Roettgen warned that “The chancellor is pursuing a foreign policy which will lead to a loss of trust in Germany among our closest partners.” Annalena Baerbock, Germany’s foreign minister, told reporters that on Scholz’s trip “it is crucial to make clear in China the messages that we have laid down together in the coalition agreement… The Chinese political system has changed massively in recent years and thus our China policy must also change.”

There is little appetite in Germany for a “business-as-usual” approach to China, something Scholz himself reiterated in his pre-trip op-ed. The question is how big of a change Scholz is willing to make, especially considering the economic costs that might come with a rupture.

Associated Press reporter Geir Moulson contributed to this story from Berlin.