The Diplomat author Mercy Kuo regularly engages subject-matter experts, policy practitioners, and strategic thinkers across the globe for their diverse insights into U.S. Asia policy. This conversation with Dr. Benjamin Tsai – senior associate at TD International (TDI) and former US government intelligence officer on Northeast Asia and the Middle East — is the 343rd in “The Trans-Pacific View Insight Series.”

What are top takeaways from the 20th Party Congress?

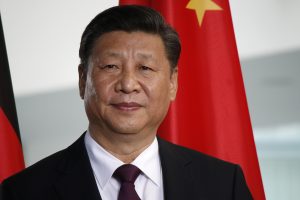

There has been a lot of commentary on Xi’s dominance at the Party Congress, and of course I agree. The congress also drove home how different Xi is from his predecessors. Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, and Hu Jintao to a certain extent all wanted the Communist Party to adapt to new trends, such as the rise of private businesspeople and professionals. For example, in 2002, Jiang Zemin introduced the “Three Represents” theory, which posited that the party should co-opt entrepreneurs but also evolve to make it relevant. In contrast, Xi seems to advocate the opposite, i.e., changing reality to fit the original mission of the party. In the political report, he repeatedly talked about never changing the nature of the party.

Second, Xi’s predecessors all prioritized economic growth, and they were willing to give up some control to achieve economic goals. Xi is putting ideology and loyalty first. With the promotion of Li Qiang and Cai Qi to the Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC), he is signaling that those who stick to “zero COVID” will be rewarded. Economic consequences are secondary.

Third, Xi has completely abandoned the idea that any societal group other than the Chinese Communist Party can be a force for good. In the 1990s, officials and academics used to discuss this concept called “small government, big society” (小政府, 大社会). It is not quite the Western idea of civil society, but it had some similarities. One example was the extent of grassroots voluntarism on display in response to the Wenchuan earthquake in 2008. The government had encouraged this limited development of civil society. With Xi, this is not possible. Any societal force that is not controlled by the party is a threat.

Examine the composition of the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC).

Much has been said about how Xi packed the PSC with his allies, such as Li Qiang, Cai Qi, Li Xi, and Ding Xuexiang. Loyalty to Xi is now the single most important criterion for advancement. Xi has done away with the informal age rule – the so called “seven up, eight down” rule – as both Li Keqiang and Wang Yang were 67.

Out of the four new PSC members, Li Qiang and Cai Qi owe their entire career trajectory to Xi. Li served under Xi in Zhejiang, and Cai served in Fujian and Zhejiang under Xi. Li Xi’s patron in Gansu was reportedly close to Xi’s father. Ding Xuexiang spent most of his career in Shanghai, but he has earned Xi’s trust. Ding likely is acceptable to the “Shanghai Clique.”

Identify indicators of internal political divergences in the CCP.

There are no overt signs of divergence, but there are disagreements over “zero COVID” and economic policy. Chinese leaders used to believe that economic growth was necessary to maintain the CCP’s legitimacy, so the slowing economy has to be worrisome to some. Xi’s concept of “common prosperity” does not inspire confidence because it has been associated with the crackdown on businesspeople and big tech companies. Even officials in his own camp, such as Liu He, tried to mitigate the effects of the crackdown by reassuring entrepreneurs. Moreover, there must be concern over Xi’s cult of personality – all the Maoist lingo about the “people’s leader” and “helmsman.”

Analyze CCP signaling for the domestic audience and international community.

Xi is signaling domestically and internationally that he is going to be around for a long time and there is no viable alternative. This is in part why he did not install a successor. Before the congress there were speculations, which turned out to be wishful thinking, that there was “pushback” to Xi’s leadership, and that maybe Xi would be pressured into changing course. I think Xi has effectively ended the wishful thinking.

Assess the impact of CCP personnel changes on the future trajectory of Xi Jinping’s leadership and its implications for China-U.S. relations.

On foreign policy, Xi wants continuity because Wang Yi is staying despite being 69 years old. Before Xi, Wang was a moderate diplomat, but his transformation into a leading “wolf warrior” clearly pleased the boss. If Qin Gang is indeed the new foreign minister, it would show that Beijing still values stable relations with the United States. Xi wants stability in military personnel as well, retaining Zhang Youxia as the first-ranking vice chairman of the Central Military Commission despite his age.

Instead of continuity, Xi wanted to shake up his economic team. It sends the strong signal that politics will guide economics. Li Qiang is less qualified than his predecessors – he will be the only premier in at least 30 years to have not served as vice premier. Ding Xuexiang, who most likely will be executive vice premier, has never led a province, municipality, or ministry. He Lifeng is likely to replace Liu He. Although He is an experienced economic policymaker, he appears to be less technocratic and independent compared with Liu He. Furthermore, Yi Gang and Guo Shuqing are probably leaving the People’s Bank of China (PBOC). Yi and Guo were well respected in China and internationally for their professionalism and competence. However, Western media reported that Xi thought the PBOC was too independent.