During the 54th ROK-U.S. Security Consultative Meeting (SCM) on November 3, strengthening the United States’ extended deterrence commitment to South Korea was a critical topic of discussion. As is usually the case, the joint communique issued at the conclusion of the SCM noted Washington’s firm commitment to providing extended deterrence to Seoul utilizing the full range of U.S. defense capabilities, including nuclear, conventional, and missile defense capabilities and advanced non-nuclear capabilities. The communique also mentioned various ways the alliance would enhance consultation in the face of an evolving North Korean threat.

Nonetheless, given its frequent invocation by U.S. and South Korean leaders and officials, “strengthening extended deterrence” has become a truism. Despite its constant mention, it’s unclear exactly how it can be effectively implemented. Furthermore, its meaning differs depending on the audience. Its effectiveness and what it means is perceived differently in Washington than in Seoul or Pyongyang.

What is clear is there’s significant concern in Seoul about both the nature and extent of the U.S. extended deterrence commitment. While South Korean concerns about the U.S. commitment are as old as the alliance – in fact, they precede it – they have taken on a newfound vigor amid North Korea’s advancing nuclear and missile capabilities and testing campaign as well as its more aggressive nuclear policy law and threat to deploy tactical nuclear weapons; China-U.S. competition; and perceptions of waning U.S. influence.

Informally, U.S. officials show frustration regarding South Korea’s concerns. How, they ask, is the U.S. commitment to South Korea not readily evident? There are 28,500 U.S. military personnel stationed in the country, there’s a longstanding Mutual Defense Treaty between the United States and South Korea, and well over a hundred thousand U.S. citizens live there. What about those very concrete realities is insufficient? Earlier this year, when a poll found 71 percent of South Koreans were in favor of the country developing its own nuclear weapons, U.S. officials were incredulous. They shouldn’t have been.

Of course, the South Korean people are aware of the U.S. presence and treaty commitment. They’re far more aware of them than are most U.S. citizens. Yet doubts persist. Strengthening deterrence, it turns out, isn’t just about such concrete realities and advanced capabilities. It’s just as much – if not more – about perception. In this regard, South Korean officials register various interconnected and contradictory concerns.

They worry that U.S. officials do not view North Korea as a threat to the same degree that South Korea does or that U.S. officials do not view it as a realistic threat to the continental United States (CONUS). Whereas North Korea’s short- and medium-range missiles – not to mention its massed artillery, large special operation forces, other asymmetric capabilities, and sheer proximity – make it an immediate and existential threat to Seoul, South Korean officials feel U.S. policymakers, despite their proclamations to the contrary, simply do not view the threat in the same way. South Korean observers feel that U.S. officials doubt North Korea could, in practice, reach CONUS with a nuclear-tipped ICBM. This runs directly counter to an alternative fear – namely, that because North Korean ICBMs might hold Seattle hostage, it could limit the U.S. response to Pyongyang’s aggression.

Moreover, even if U.S. officials do genuinely believe North Korea possesses such a capability, South Korean officials fear the U.S. government’s attention is taken up by other priorities, like the war in Ukraine and confronting China, which supersede dealing North Korea. In other words, even if U.S. policymakers do see North Korean capabilities as a threat to CONUS, South Korean officials worry that they do not have the bandwidth to address it.

Another concern among South Korean officials is that the United States would not, in fact, retaliate against North Korea with U.S. nuclear weapons were the latter to attack South Korea. Or, contradictorily, South Korean officials are concerned that the U.S. would, in fact, retaliate with nuclear weapons but without proper consultation. The absence of a formal South Korea-U.S. alliance nuclear planning group and U.S. nuclear weapons policy, which gives the U.S. president sole authority to order the use of nuclear weapons without consulting anyone else, reinforces the lack of clarity and concern.

There’s also a concern among South Korean observers that the consensus view within the U.S. government is that North Korea would never actually test the United States’ extended deterrence commitment by executing a full-scale attack or using nuclear weapons against South Korea. So, accordingly, whereas U.S. officials ask why North Korea would test the alliance in that manner – not believing it ever actually would – South Korean observers focus on what the United States and the alliance would do if it did. They feel there is insufficient clarity on this point. Deeper consultation, they argue, is necessary.

However, on the U.S. side, some people highlight risks that might result from deeper consultation, which are just as beset by contradiction as are South Korean concerns. Some U.S. observers note that with deeper consultation, the South Korean could make requests of the United States that the latter cannot or will not fulfill. This itself could strip away illusions that have papered over long-term differences and will force both sides to face any differences from the perspective of equals or near-equals. Both sides would have profound difficulties doing so given the longstanding and historically rooted psychologies about their respective roles in the alliance.

With more consultation and a keener awareness on the South Korean side regarding the limits of what the United States can or will provide, the South Korean could become even more determined to chart its own course, including its own independent nuclear deterrent. U.S. observers hold that this would overturn decades of U.S. and South Korean government policy on denuclearization, give North Korea a ready ex post facto justification for its own nuclear weapons program, fundamentally undermine the NPT, and result in further horizontal proliferation in the region and likely beyond.

An alternative concern among U.S. observers is that with closer consultation and awareness of U.S. nuclear policy and planning, the South Korean might decide the opposite, namely, that the use or threat of nuclear weapons on its behalf by the United States is untenable. This would signal South Korea’s rejection of the U.S. extended deterrence commitment (at least its nuclear component), further undermining its credibility. In either case, deeper consultation could reveal certain truths more lucidly. The alliance may have a difficult time navigating it.

Some on the U.S. side also have expressed frustration with the apparent fetishization of the nuclear issue. So much emphasis is put on the nuclear component of U.S. extended deterrence that it reduces the focus, resources, and effort that could and should be into other non-nuclear components of deterrence. It prevents South Korean officials from recognizing the full range of U.S. capabilities, including advanced non-nuclear ones. Over-emphasis on the potential threat or use of nuclear weapons against North Korea is also so extreme and disproportionate a threat that it begins to lack credibility. It may actually enhance North Korea’s willingness and even appetite to test the alliance, evinced by its recent array of missile tests before, during, and after the deployment of U.S. strategic assets to the Korean Peninsula.

To be sure, the Yoon administration’s current stance is that it is not seeking the return of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons to South Korea or a NATO-style nuclear sharing agreement. Of course, given Pyongyang’s steadily advancing capabilities and willingness to test the alliance, that stance could change. Yet, even if South Korean officials were fervently seeking such measures, those are decisions made in Washington and not in Seoul, further reinforcing the degree to which certain decisions having critical effects on South Korea’s national security are not entirely in its own hands. In that regard, Yoon administration officials have eagerly sought to tighten alliance relations.

Accordingly, there has been a notable uptick in alliance consultation and cooperation, including: the expansion in the size, scope, and type of alliance military exercises on and around the Korean Peninsula; more systematic and overt public communication about such exercises; deployment of U.S. strategic assets for the first time in years; and ramped up U.S.-South Korea-Japan trilateral cooperation as well. Furthermore, U.S. and South Korean defense and security officials have been meeting and communicating much more frequently. Restarting the Extended Deterrence Strategy and Consultation Group (EDSCG) is a prime example, even though, according to some South Korean observers, the United States was reluctant to restart it.

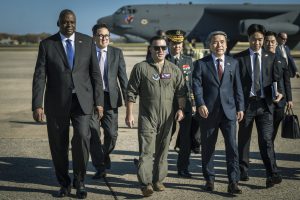

Moreover, South Korea’s Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman General Kim Seung-kyum’s recent visit to Strategic Command (STRATCOM) is of note. In the early 2000s, the United States centralized its nuclear war planning in the newly created U.S. STRATCOM, moving it out of the geographic Combatant Commands. The short-term result at that time was that U.S. nuclear policy and planning was further removed from South Korea-U.S. dialogues. If the alliance’s public pronouncements are taken at face value, then such meetings may indicate increased efforts to actively cooperate in the deployment of U.S. strategic assets, joint drills, and the expansion of strategic dialogue.

Although South Korean defense and security officials were purportedly seeking – but did not get – a new nuclear planning group at last week’s SCM, the meeting did show a new level of focus and agreement on the need to tighten planning, consultation, and the discussion of continencies and options in the face of an increasingly unstable peninsular environment. Nevertheless, what matters most is how each side interprets those commitments and moves to implement them.

There are reasons to be skeptical. First, various alliance consultative mechanisms proliferated over the last decade, which were meant, in part, to enhance extended deterrence vis-à-vis North Korea and reassure Seoul regarding the credibility of that commitment. Instead, North Korea has steadily advanced its capabilities and been more brazen in its willingness to test the alliance. Meanwhile, Seoul’s doubts have only worsened. Put simply, the creation of deeper consultative mechanisms to strengthen extended deterrence got us to the point of needing more consultative mechanisms to further strengthen extended deterrence.

Second, we cannot divorce these developments from the broader political context. The alliance was profoundly damaged by four years under President Donald Trump. The recent uptick in alliance consultation does not change that fact. Trump supported the idea of South Korea (and Japan) getting its own nuclear weapons while simultaneously denigrating the alliance. By all indications, Trump is on the verge of announcing his candidacy for 2024. Even if we assume the recent pronouncements at the SCM indeed mark a fundamental change in the level and depth of alliance consultation, how would they hold up during a second Trump administration?

Currently, the alliance uses measures and messaging that, by all appearances, not only lack credibility in Pyongyang’s eyes but also provides it the justification it needs to execute its own tit-for-tat retaliatory measures. With self-defense increasingly framed in terms of preemption by both Seoul and Pyongyang and former South Korean commanders openly promoting development of Seoul’s nuclear latency, there is an increasing risk of misperception, miscalculation, and sudden escalation. Under these circumstances, continuing to mouth truisms simply won’t do.