Joko Widodo often uses Javanese aphorisms to make a point. “Lamun sira sekti, aja mateni” is one of his favorite sayings. Slowly and rhythmically, Indonesia’s president recited the line as a voiceover for a meme shared on social media in 2019. Translated, it means: even though you are powerful, don’t knock others down. In short, don’t be a bully.

“Lamun sira sekti . . .” feels like an appropriate theme for Indonesia’s G-20 presidency.

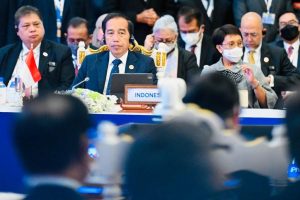

Widodo, popularly known as Jokowi, will be presiding over the group’s annual summit in Bali this week. In an interview with The New York Times, he described the event as perhaps the “most difficult” G-20 meeting yet. The war in Ukraine is the main polarizing issue. Mixed messages over whether Vladimir Putin would attend kept the organizers in suspense until last week. Finally, the Russian president sent word that he would not make it. Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, invited as a guest, indicated he might make a virtual appearance.

Jokowi is now free to turn his attention to other contentious relationships around the G-20 table. Both Xi Jinping and Joe Biden will be in the room. He can also focus on the summit’s original agenda, namely post-pandemic economic recovery.

Jokowi does not aspire to be a global statesman.

Indonesia’s president has a well-documented aversion to international diplomacy and its trappings, focusing instead on domestic issues. He avoids power huddles, famously skipping the United Nations General Assembly meeting eight years in a row. But with Indonesia taking on this year’s presidency of the G-20 for the first time in 2021, Jokowi faced pressure at home and abroad to prove he was more than just an “event organizer.”

In July, the former mayor of Jakarta stepped outside his comfort zone on a “peace mission” to urge an end to the war in Ukraine. He framed the conflict in pocketbook terms, a bread-and-butter problem for developing countries rather than an existential struggle at the heart of Europe. The Financial Times noted recently that the war was not an “all-consuming preoccupation” for Indonesians. “A lot of Widodo’s attention is on the second-order economic effects of the war and the impact it has on driving up global food prices,” it reported.

Indonesia is a top wheat importer, and Ukraine was one of its primary suppliers pre-invasion. Grain shipments are the mainstay of a thriving instant noodle industry, the world’s second-largest after China. Indonesian brands have popped up in unexpected places. A Russian news agency recently posted photos of Indomie’s Mi Goreng Hot and Spicy at an abandoned army base in eastern Ukraine.

Jokowi had hoped the peace mission would deliver a breakthrough, but he returned empty-handed. On the issue of grain shipments, he made modest progress. He passed on a message from Zelenskyy requesting safe passage for ships sailing between Odessa and Istanbul, which Putin said he would provide. The Indonesian president’s initial optimism that Putin might agree to a ceasefire was misplaced. David Engel, a veteran diplomat who heads the Indonesia program at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, called the president’s visit to the Kremlin “naive and ill-judged.”

Europe’s bloodshed and fossil fuel politics are not Jokowi’s cup of tea. His diffidence on the world stage belies a “laser-like focus” on a bold domestic agenda dedicated to making Indonesia a developed nation by 2045. His foreign policy is geared toward fundraising for Indonesia’s many infrastructure projects, including the $33 billion capital city of Nusantara in the forests of East Kalimantan. The G-20 summit is a milestone for Jokowi, an opportunity to showcase Indonesia’s potential in the presence of world leaders and deep-pocketed corporations.

The guest list includes tech icons like Elon Musk and Bill Gates, who may make an in-person or virtual appearance. Earlier this year, Jokowi shared a picture of his visit to the Texas location of SpaceX. He appears to enjoy a genuine rapport with Tesla’s founder. Musk tweeted that they discussed “exciting future projects!” Tesla has reportedly agreed to build a battery factory in Central Java. In an interview with the editor-in-chief of Bloomberg News, Jokowi outlined his expansive vision for Indonesia in a carbon-free economy. He plans to set up a “huge ecosystem” that will make the Southeast Asian nation a global hub for the electric car industry.

His goals are lofty, yet Jokowi comes across as modest and unassuming. The antithesis of a strongman, the Indonesian president may not be the right person for a peace mission to Moscow. But his aura of calm could come in handy for moderating heated G-20 negotiations. Jokowi once told his biographer he maintains his composure by following the Javanese philosophy of ojo kagetan – don’t get excited.